Culture

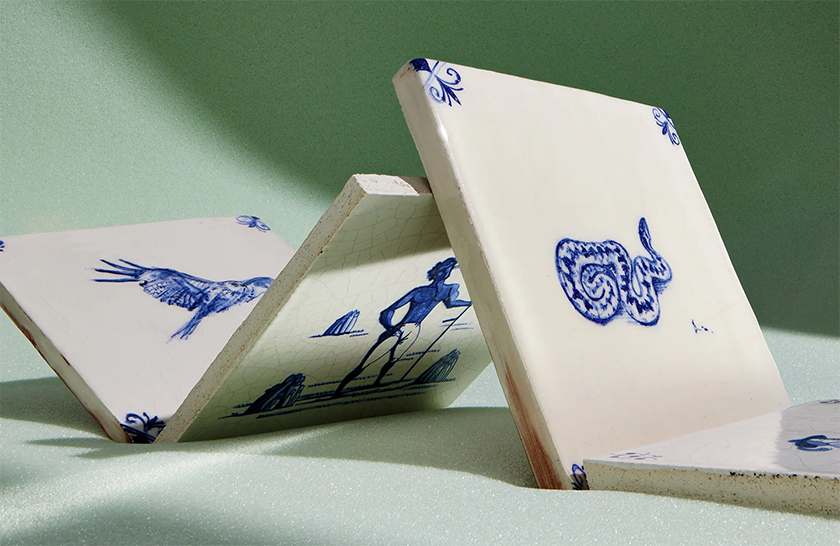

A different kind of Delft tile

Circa 1700, Adam and Eve being banished from the Garden of Eden.

Image courtesy of: House & Garden UK

Even if you don’t know exactly what it is, you recognize Delft tile as something that is “old-fashioned.” The main period of tin-glaze pottery in the Netherlands was 1640-1740. At this time, Delft potters started to personalize tiles with their own monograms or other distinctive factory marks. A sort of “union of the time,” the prestigious Guild of St. Luke admitted ten master potters during 1610-1640 and twenty potters during 1651-1660. Physical space was an issue, but a large gunpowder explosion in 1654 freed up some of the breweries that were turned over to pottery makers looking for larger premises.

Around 1615, Dutch potters began coating their pots in white tin-glaze rather than only covering the painting surface and coating the rest with a clear ceramic glaze… this effectively gave depth to the fired surface and a smoothness to the cobalt blues. With a close resemblance to porcelain, potters began to replicate Chinese porcelain which, up until that point, was only available to the upper class. Courtesy of Christiaan Jörg, “Potters now saw an opportunity to produce a cheap alternative for Chinese porcelain. After much experimenting they managed to make a thin type of earthenware which was covered with a white tin glaze. Although made of low-fired earthenware, it resembled porcelain amazingly well.”

Albert Blue Delft Tiles come in a minimum order of forty tiles. For many years, the California artist Lesch-Middelton has been etching ceramic tiles and vessels with ancient patterns. Recently, the artist debuted a collection that includes seven tile designs that are available in six-inch squares.

Image courtesy of: Remodelista

In essence, Delft pottery was a direct response to the popularity of Chinese blue and white porcelain. Initially, the pictorial representations on tiles were limited to the images on Chinese porcelain which were imported by the Dutch East India Company in mass quantities. However before long, Dutch potters began incorporating scenes more familiar to them. For example, snapshots from Dutch life that included windmills, tulips, farm workers and animals, and sailboats.

By the end of the eighteenth-century, the appeal of Delft tiles had ceased and the production came to a virtual halt. At that time, similar tiles could be manufactured more cheaply in Britain and there did not seem to be a reason to continue the laborious craft that had fallen out of grace. However today, a group of ceramists have taken it upon themselves to revive the elegant craft.

Vintage botanical tiles with accents in the corners.

Image courtesy of: Style By Emily Henderson

Dutch Tile Inc. for example has been importing authentic Dutch tiles to architects, interior designers, contractors, and homeowners for over four decades. Formerly known as the Amsterdam Company, the tiles are all hand-formed and hand-painted in The Netherlands. The ceramists use the same historical methods that date back four centuries. Courtesy of the company’s website, “Pin holes in the tile corners, beautifully nuanced tin glazes and the slight variations in shape, thickness and color are all hallmarks of the craftsmanship.”

As the only factory in Holland that hand-makes and hand-prints all the tiles on site, attention to detail lays partially in the fact that master artisans pass their knowledge down to fellow artisans. The process entails nine distinct steps that must be followed precisely.

Ottelien Huckin’s Figurative Tile in Blue. Each tile in hand-painted in Huckin’s London studio.

Image courtesy of: Ottelien Huckin

Aviva Halter, a British ceramist receives commissions rather than concentrating on mass-production. Aligning closely with traditional Dutch iconography, Halter typically creates one-offs that are painting with her customers’ treasures. She hopes that her detailed offerings (courtesy of The New York TimeS) “make permanent ‘what we value and love about life.'” Halter hand-rolls, paints, and glazes everything at her Dorset farmhouse workshop.

The young Ottelien Huckin draws bodies not normally celebrated in art. For example, Huckin draws voluptuous female figures onto four-inch square tiles. The artist hopes (courtesy of her website), “to reveal the nude in an autonomous, empowered and sensual way by reinterpreting old master drawings with my own life drawing observations and intuition.”

Blue and white tiles by British artist Paul Bommer.

Image courtesy of: New York Times

The centuries-old craft is certainly not disappearing; and we love that artists who are working to reclaim this traditional design element. Updating the motifs is one way to modernize Delft tiles and present them in a way that is appealing to a broader clientele.

The British artist Paul Bommer has made a name for himself by updating the images that we normally associate with Delft tiles. Courtesy of an article by Max Norman for The New York Times Style Magazine, “Boomer, too, is writing a different kind of person into history with his playfully sexy and obscene creations, with which, he says, he seeks both to ‘honor and subvert.'” The effect is fun and saucy… and probably appeals to a those that would normally shun Delft tiles as too traditional for their likes. We love this subtle way of pushing the boundaries of design!