Architecture

A tribute to Richard H. Driehaus

Richard H. Driehaus died on March 7th at the age of 78. The photograph of the investor in his Chicago house is circa 2009.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: William Zbaren

Richard H. Driehaus passed away in March…the “Champion of Classic Architecture” was as much a Chicago landmark as many of the landmarks he restored in his beloved city.

The founder, CEO, and chairman of Driehaus Capital Management, one of the world most successful investment firms, started at a young age. Since the age of 13, the investor was immersed in the stock market taking big gambles on risky rising stocks. In 2000, he was named by Baron’s as one of the 25 most influential mutual fund figures of the 20th-century. He used his fortune to do a lot of good, especially in Chicago where he yielded the city a palatial museum that celebrates the Gilded Age. In addition, he took it upon himself to restore many of Chicago’s most amazing structures…saving them from ruin. He liked to say that he turned a grade-school coin collection into a fortune that he used to preserve Chicago’s classical architecture buildings.

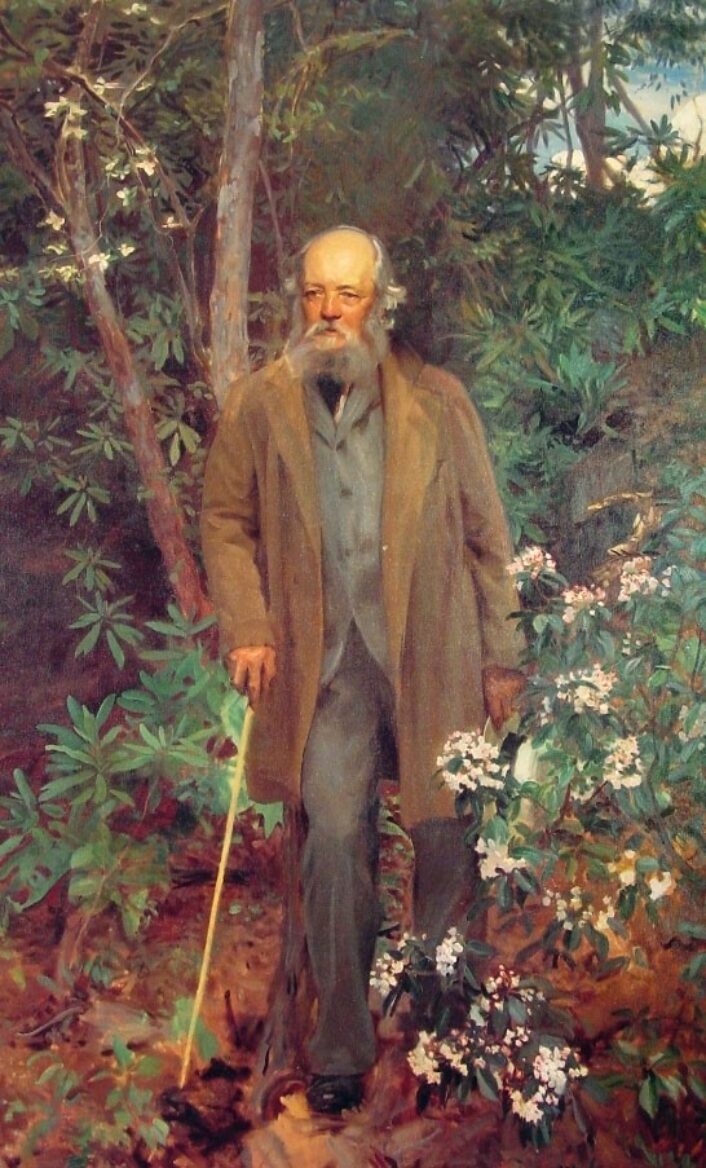

Driehaus at the 2019 Richard H. Driehaus Prize ceremony at the University of Notre Dame.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Heather Gollatz-Dukeman

Driehaus also established a $200,000 annual price in his name for classical, traditional, and sustainable architecture. This prize was meant to be a counterbalance to the $100,000 Pritzker Prize established by Chicago’s Pritzker family. Driehaus viewed this as a (courtesy of a New York Times article by Sam Roberts) “validation of modern motifs that were a “homogenized” rejection of the past.”

The first Richard H. Driehaus Prize awarded to an American laureate was given three years after the prize was establishment. In 2003, the first prize was presented at the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture to Leon Krier. The designer sketched Poundbury, a model British town built according to the Price of Wales’ architecture principles. In 2006, the South African-born Allan Greenberg was awarded the prize for redesigning the State Department’s Treaty Room Suite.

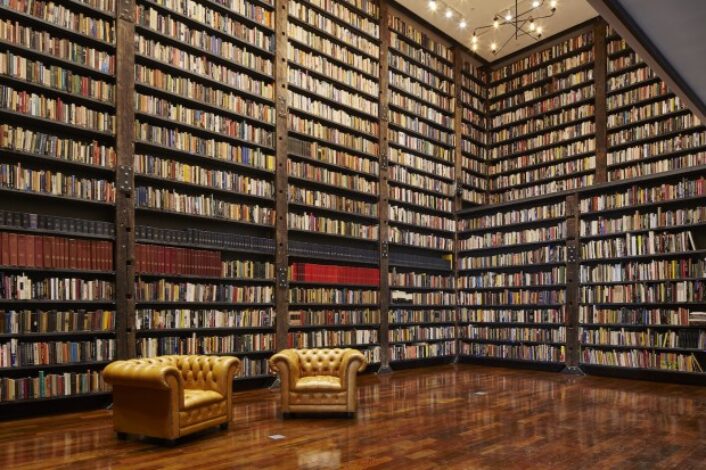

The Richard H. Driehaus Museum opened to the public in 2008. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and designated a Chicago landmark on September 28, 1977.

Image courtesy of: The Architect’s Newspaper, photographed by: Alexander Vertikoff

The Richard H. Driehaus Museum of Decorative Arts opened to the public in 2007. The museum was housed in a neoclassical mansion on Chicago’s Near North Side; it was devoted to art, design, and architecture from the 19th-century to present-day. Originally, the mansion was designed by Edward J. Burling for the wealthy banker Samuel M. Nickerson; however, it was not in good shape when Driehaus bought it. The investor spent his personal money to restore the Gilded Age mansion to its original luster. The 1883 structure serves as a museum that includes some of Driehaus’ personal collection of objects and art from the private Driehaus Collection of Fine and Decorative Arts.

The interior is made of marble, onyx, carved international and domestic woods, stained glass, and glazed tiles. The Nickerson family’s original furnishings, in addition to decorative arts of American and European origin from the late 19th century and early 20th-century, fill the massive structure.

Ransom Cable Mansion.

Image courtesy of: Antunovich Associates

Driehaus’ love for classic architecture was most certainly a function of his upbringing. Born to a father who designed coal-mining equipment and a mother who worked as a secretary, Driehaus was the oldest of three children. As a boy, he ran a newspaper-delivery route in Chicago, not far from his middle-class neighborhood of Brainerd. At that young age, he was awed by the ornate homes that were a juxtaposition to his family’s bungalow. He always remembered that his father desired to move to a better neighborhood where he could build a Tudor or Queen Anne home. Driehaus later said, “What my dad couldn’t do, I wanted to do.”

A champion of the ornate, Driehaus’ company renovated the former Ransom Cable Mansion to serve as their Chicago headquarters. The Richardsonian Romanesque-style mansion was built in 1885-86 for the family of the president of Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railway Company, Ransom R. Cable. During the rehab, period lighting fixtures were installed along Wabash and Erie Streets, along with new trees, landscaping, and landscape planters. As intended, the property looked as though it stepped back in time. The mansion’s interior was redesigned under strict rules to ensure that the building’s original look remain undisturbed; wood moldings, marble inlays, and plaster details look just as they did in the past.

Glanworth Gardens on the north shore of Lake Geneva is Richard H. Driehaus’ lake estate. The Georgian Revival building was built in 1906…for years, it has been the place where Driehaus held his legendary birthday galas!

Image courtesy of: Lakeshore Living, photographed by: Clint Falinger

Driehaus loathed modern architecture, especially Modernism. He told Chicago Magazine in 2007, “The problem is there’s no poetry in modern architecture. There’s money—but no feeling or spirit or soul. Classicism has a mysterious power. It’s part of our past and how we evolved as human beings and as a civilization. It’s more organic, more individual, and more interesting.”

Nevertheless, Driehaus supported new traditional projects, often awarding his famed prize to practicing architects who design in either a classical or a traditional style. Further cementing his thoughts, he told Michael Lykoudis in 2012, “I believe architecture should be of human scale, representational form and individual expression that reflects a community’s architectural heritage.

Thank you Mr. Driehaus for all you did for Chicago’s architecture… and beyond!