Fine Art

Anna-Eva Bergman

“Untitled,” 1952.

Image courtesy of: Artsy

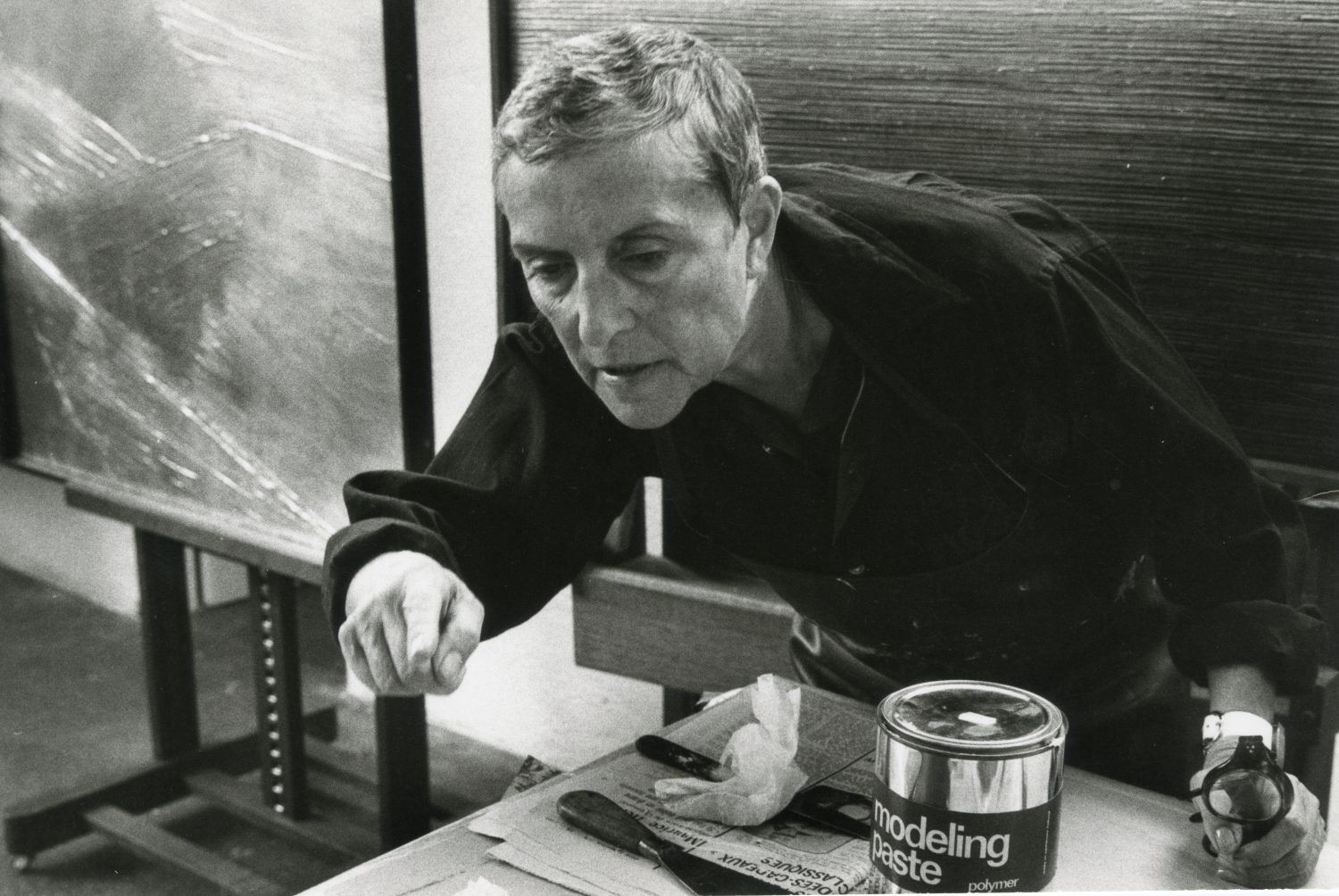

For perhaps the first time, the Norwegian abstract expressionist painter Anna-Eva Bergman is getting her time in the spotlight. This year, thirty-years after her death, Bergman is the feature of two shows: Paris’ Musee d’Art Moderne and Oslo’s National Museum.

Most of Bergman’s paintings were influenced by her beloved landscapes; particularly impressions from two trips to Northern Norway during the summers of 1950 and 1964. Bergman recorded her accounts from a coastal steamer’s deck, the scenery that she observed were stunning fjords, jagged mountains, endless ocean, and the Northern Lights.

“No. 4-1957 La grande montage,” 1957. Oil and metal sheet on canvas.

Image courtesy of: Aware Women Artists

In addition to landscapes, Bergman was also influenced by the company she and her husband, the German-French painter Hans Hartung, kept. The pair met in 1929 in Paris while Bergman was studying at an academy; that same year, the two got married. During the wartime period, the couple frequently visited with other avant-garde artists including Vassily Kandinsky, Joan Miró, and Piet Mondrian. Even though the couple was only married for nine years prior to getting divorced, the pair remarried in 1952 and rejoined the vivacious Paris art scene. This time, Alexander Calder and Sonia Delaunay-Terk were their frequent counterparts; in the 1960, Bergman befriended Mark Rothko.

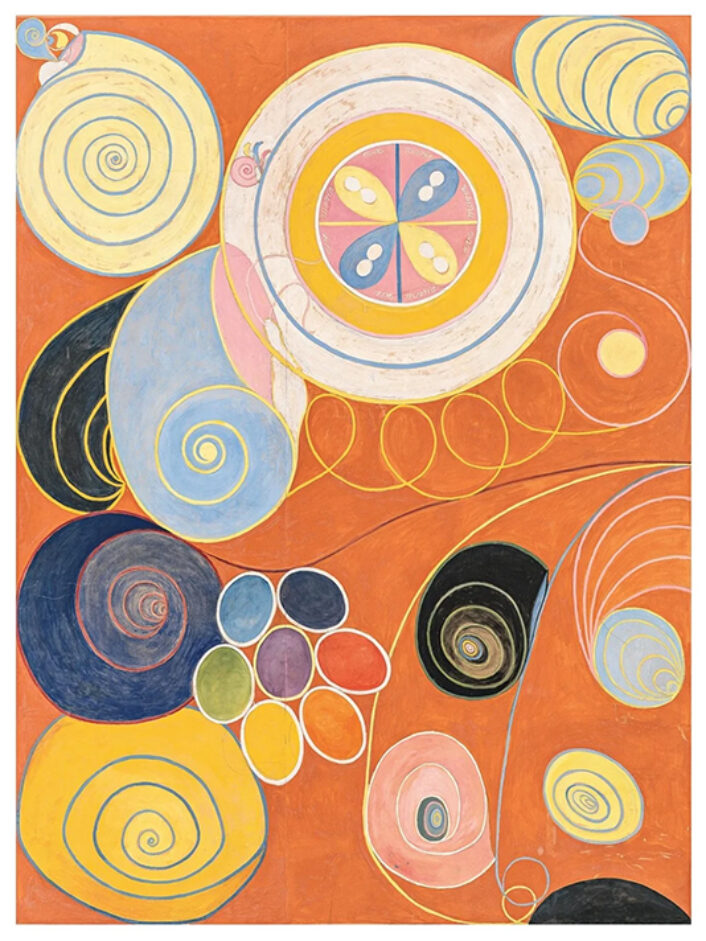

Bergman’s early paintings were mainly nature-inspired… filled with lines and fields; the painter’s style changed drastically in the early 1950s. For the latter part of her career, Bergman’s paintings were abstract; her canvases often conveyed a “mystical representation of nature.”

“Anna-Eva Bergman in her studio in Antibes”

Image courtesy of: Aware Women Artists, photographed by: Francois Walch

Bergman’s paintings were functions of (courtesy of Masjonal Museet) “exact calculations and pictorial constructions, and her imagery developed almost scientifically. She reduced the forms, employed geometric shapes, and repeated her preferred motifs with different variations. Underlying the compositions is an understanding of the golden ratio as a principle of construction, which she used to support a universal validity and an expression of harmony and stability.”

In her paintings, two elements play a recurring role: rocks and stones. Bergman was clear in that she was fascinated in the earth’s “material substances;” she was also interested in celestial motifs… stars, horizons, and planets would often converge with boats, mountains, and caves. Bergman was masterful at blurring the lines between where one subject ends and another subject begins. For example, as stated by Numero, “At what point does a mountain peak become a raised sail? When does the open sea turn into a cave? The stele in this instance easily conjures an upright figure, but also implies the opening of a void.”

“N°63-1961 Big universe with small squares,” 1961. Oil and metal sheet on canvas.

Image courtesy of: Museum of Non Visible Art, photographed by Claire Dorn

Moving to the South of France later in life affected Bergman’s work immensely; at the center, it was always the unique light and unparalleled landscape of Scandinavia. Oftentimes, Bergman used reflective surfaces of gold or silver leaf in conjunction to delicately adjusted tones.

Bergman’s use of metal sheets was inspired by the altarpieces found in Norwegian churches from the Middle Ages. The painter personalized this technique by combining the material to create “pure forms.” This was a style that Bergman never abandoned, even as her painting changed throughout her career.

Inside the Antibes Hartund-Bergman Foundation.

Image courtesy of: En Vols

Bergman and Hartung’s Antibes property served as their two studios for the latter part of their careers. After both artists died, it became the Hartung-Bergman Foundation. Set in a field on the hills in Antibes, the pair designed the home’s architectural plans themselves. The 2-hectare olive grove that served as their plat and the villa and two studios were inspired by architecture of the Mediterranean.

Today, the Foundation’s mission is to oversee the artist’s estate. Last year, the Foundation opened to the public for the very first time following a two year renovation. Thomas Schlesser, the Foundation’s head and someone who understood Bergman quite literally was quoted as saying “Her ambition was clear, to make people experience in front of each of her paintings the feeling they get when they enter a cathedral.” A wonderful sentiment indeed!