Architecture

Berlin’s hidden complex

Glass facades at the Ökohaus complex.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times Style Magazine, photographed by: Robert Rieger

Frei Otto, the German architect who is most known for his use of lightweight materials and the roof he designed in Munich for the 1972 Olympic Games, questioned the role of architects throughout his entire career. He strongly believed that, “Each man can create his own individual environment.”

He was inspired by seeing Germany “in flames” during World War II and dreamt up (courtesy of a New York Times Magazine article by Megan O’Grady), “a new kind of architecture that would be transparent, democratic, nonhierarchcial, and free.” Following the war, there was a push by the visionaries that had escaped the Nazis in the 1930’s. They worked to design in the style that Hitler despised and rejected. Former Bauhaus innovators such as Ludwig Mies van den Rohe set forth to rebuild their cities. During the early 1980s, prior to reunification when Modern buildings were once again unpopular, Otto imagined his “Ökohaus.”

Otto called himself the “anti-architect.”

Image courtesy of: The Offbeats

Something most post-war architects had in common was to design with the intent on living more closely with nature. In fact, Otto imagined the vertical structures of Ökohaus three decades prior… the original idea called for an even taller format near New York’s Central Park.

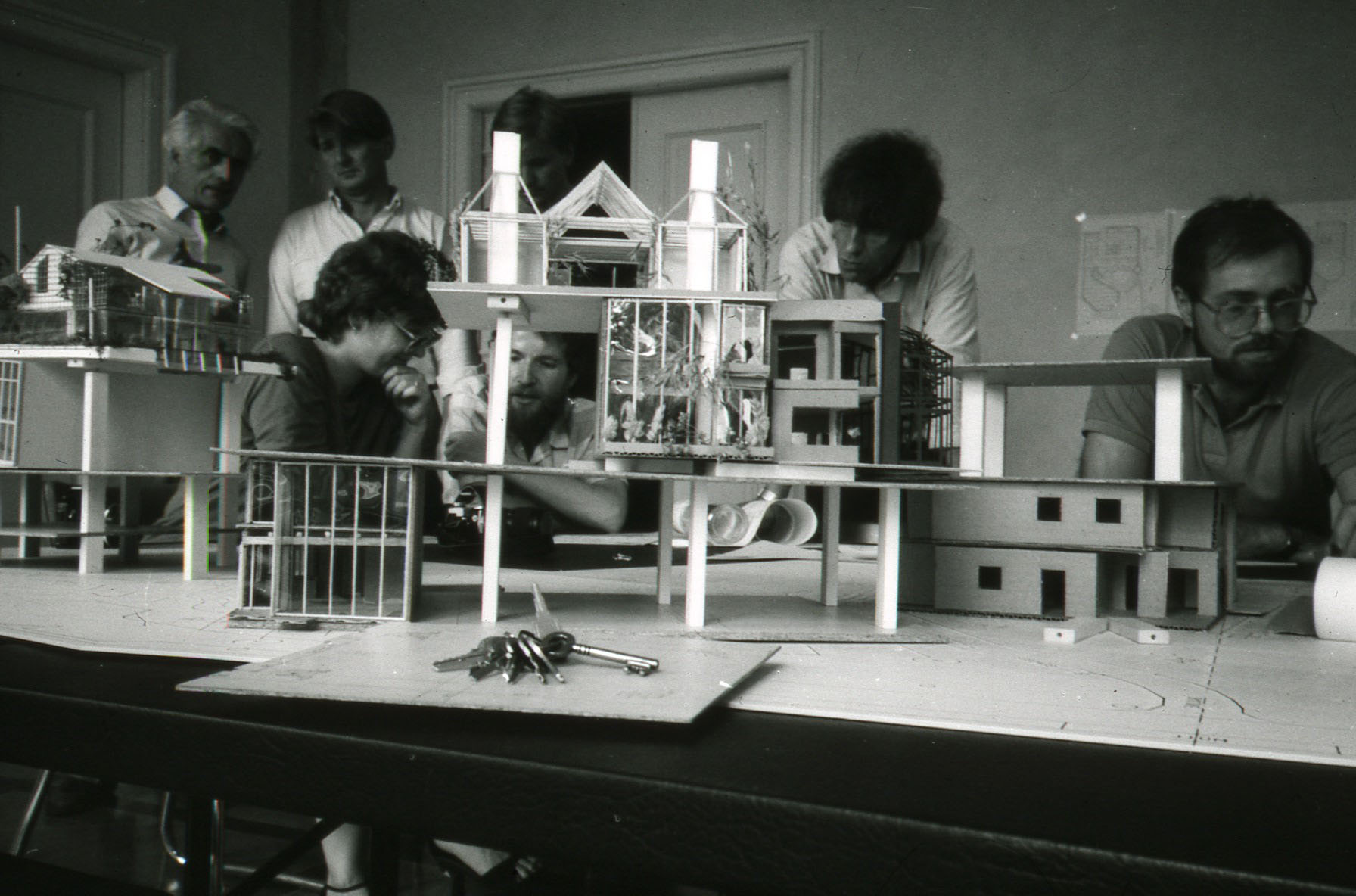

Otto was commissioned for this project for the second International Building Exhibition. Interbau 87 was designed to be built in an unpopular part of West Berlin, near the oppressive Berlin Wall. Ökohaus was completed in 1992 on a piece of land that was previously home to the Vatican embassy. Making certain to preserve the site’s gigantic chestnut tree, the individual townhomes became known as treehouses.

The structures come together to make a hodgepodge of styles with varying materials and references. It almost looks as though these are abandoned buildings in the middle of an urban jungle.

Image courtesy of: Solidar Architekten

Otto desired “a three-dimensional garden city” with use of public gardens and low density. The three concrete tree-like designs each had trunkline columns with platform branches. Deliberately leaving the structures open, the idea was that the prospective owners have the ability to completely customize their home environments. The project would be deemed a success if upon completion, there was a varying patchwork of materials and styles.

The third “tree” was meant to be rented and owned by the city. For this part, Otto designed townhouse-like apartments that had double-decker glass on the branches. The complex contains 26 homes, each roughly 1,400 square-feet. In addition, there are outdoor spaces… private yards for the first-story homes and “hanging gardens” for the upper level units.

Concrete, wood, brick, and glass are all hidden by the overgrown greenery of Tiergarten.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times Style Magazine, photographed by: Robert Rieger

Berlin newspapers published articles in order to attract potential “co-builders” and “co-participants.” Immediately, many applicants inquired and wanted to join the social experiment even though from the outside, it looked like a jungle. The majority backed out after realizing the costs and unknown factors. At the end, 18 families came together for this special “building community.” An inhabitant, Jurgen Rohrbach said,” It was interesting- for my family and for myself as an architect- to be able to develop the design of my own house, according to my own needs.”

The one caveat was an agreement that if a member fell upon financial difficulties, the other members would help him out in order to keep the project from collapsing. As with most building projects, the costs were more than initially projected. All-in-all, nine different architects were involved; they inserted the two-story buildings into the infrastructure. The stand-alone houses appear to be stacked one on top of the other; although interestingly, this was done so that the lower houses do not structurally support the upper ones.

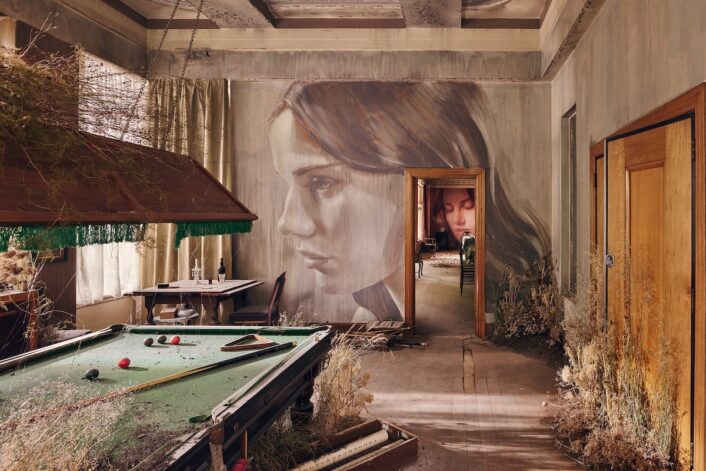

Inside Peter Heimer’s Okohaus space. Heimer, a contemporary-art consultant and dealer bought the space in 2011. He was very careful to remain true to Otto’s vision and style.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times Style Magazine, photographed by: Robert Rieger

Today, seventy percent of the original owners still reside in their homes. Many around seventy years old, they take great pride in the fact that they are united by one common factor- Otto’s larger ideals. They stand behind the idea that you can live “low-key” within a city and that individual freedom can succeed within a collective.

Who knows what Otto would have thought of today’s cities? As more and more people leave urban areas for varying reasons… education, politics, finances, safety… there is no doubt that some who are moving to quieter pastures are the very people that made our urban environments what they were. We love this statement from Megan O’Grady, “The Ökohaus isn’t just an ecotopian fairly tale; it’s a model of flexibility and optimism, conceived in an era when we lived with less fear of the unknown and of each other, a time when we were still game and open to ideas that spoke to more than the bottom line, back before we lost our belief in the possibility- via beautiful, innovative design- of a better common future.” Perhaps we should all ruminate on the for a while?