Denise Scott Brown in Las Vegas, 1968.

During her 1966 tenure in Southern California, Scott Brown took a life-altering trip to Las Vegas. Two years later, she returned with Venturi, Steve Izenour, and some Yale students to study the architecture and spacial planning of “the Strip.” The trip yielded collective research that produced one of the most widely-referenced texts of 20th-century architectural theory, “Learning From Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form.” The book was published in 1972.

Image courtesy of: The Guardian, photographed by: Robert Venturi

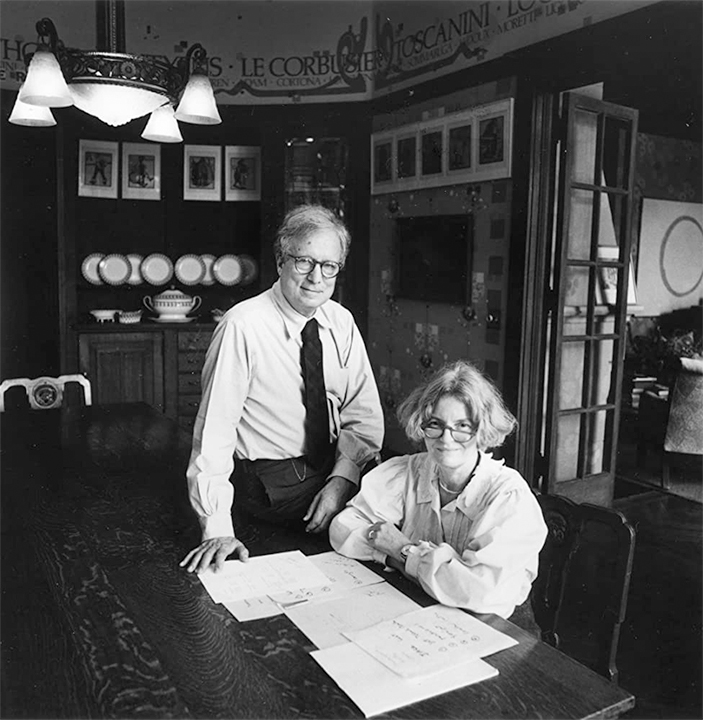

To say that Denise Scott Brown has been revolutionary in architecture would be an enormous understatement. The 88- year-old has been a member of architecture’s elite ranks for over fifty years, well into her ninth decade. For years, Scott Brown was married to Robert Venturi, her partner in both life and work. This sound merger brought about many professional collaborations… however in 2013, two architecture students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design launched a petition to have Scott Brown retroactively recognized by the Pritzker Prize, the most prestigious award in the design field which was given to Venturi in 1991 (for shared work).

The pair…

Their scale of work ranges from decorative arts to furniture, urban design and planning, and architecture. Scott Brown and Venturi were also well known for their writing.

Image courtesy of: Archinomy

Sadly, it was a very long time before Scott Brown received her well-deserved due. The South-African raised, Philadelphia-based architect, urban planner, and theorist met Venturi when the two were young professors at the University of Pennsylvania. The pair met in 1960, got married in 1965, and became architectural partners in 1967.

Scott Brown’s earliest architecture inspirations were formed by her mother, also an architect. It is said that her early childhood was a study in contrasts: the modernism of Johannesburg and the vernacular architecture of Zuzuland as racial segregation raged in the background. Scott Brown credits her Johannesburg childhood with forming the ideas that, later in life, made her one of the leading experts on urban design.

Chippendale chairs, set of four. Knoll International, 1984. Made of laminate over plywood, upholstery.

Image courtesy of: Wright

By the late seventies, Scott Brown and Venturi had begun designing furniture for Knoll. The pair reinterpreted the shape of traditional Chippendale chairs in a two-dimensional silhouette clad in various modern-day patterns.

Each had a specific role, Venturi would study chairs from different eras such as Art Deco and Queen Anne while Scott Brown would create the pattern to be applied to the form. The “Grandmother” design that they created featured a floral, quilt-like pattern interspersed with hash marks. Trying out samples on cotton and sateen, Scott Brown also played with an abstract black-and-white design. Scott Brown said that with time, this pattern began “to look more like the black-and-white blobs on the covers of composition notebooks that American children use in school.”

Designed jointly by Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi, Sainsbury Wing National Gallery in London

Image courtesy of: Bigmat International Architecture Agenda, photographed by: Timothy Soar

Sadly though, it took decades for Scott Brown to get her well-deserved recognition. When Venturi won the Pritzker Prize, the most prestigious award in architecture, there was no mention of Scott Brown. The jury cited numerous projects that were completed in collaboration such as the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery in London; however, she was shunned. Twenty two years later, a petition to retroactively recognize her by the Pritzker Prize went viral and received over 20,000 signatures and widespread support by past Pritzker Prize laureates such as Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, and Frank Gehry. The petition claimed, correctly, that the prize should have been awarded for the duo’s JOINT body of work .

Disappointingly, the jury issued a statement claiming that they could not reverse a prior jury’s decision. This pointed to testament that there was ongoing chauvinism within the architectural establishment and that it was well out of touch with the times.

Designed by Denise Scott Brown and Robert Vertuni, Gordon Wu Hall at Princeton University, New Jersey, 1983.

Image courtesy of: Culture Trip, photographed by: Mark Wargo

At the age of 81, Scott Brown is still very much in demand at architectural events; she is also frequently asked to give lectures and present papers. While at an event that introduced the Spanish translation of her book “Having Words” to a group, Scott Brown said, “In the 70s and 80s we thought we were suffering alone, by the 90s I was still having a great deal of trouble and when I said anything it made powerful men very angry. By the 90s, we had to tell them we were not going to suffer in silence. I watched the advent of women in my field. Early on, if I went to a conference there would be one woman and one black in a hall with 500 white men. I think what happened to me could still happen, some of the inequities remain.”

She stated that the Pritzker Prize was based on the fact that great architecture was the work of a “single lone male genius” at the expense of collaborative work. She concluded, “It wasn’t just an oversight. They made a conscious decision not to include me.”