Fine Art

Doris Lee

“Thanksgiving,” 1935. Oil on canvas. The painting won the prestigious Logan Medal of the Arts award when it was first exhibited in The Art Institute of Chicago. The customs and rituals of Thanksgiving and the depiction of family life in Lee’s sweet manner were especially appealing to a country that was in the midst of the Great Depression.

Dimensions are: 28″ x 40″

Image courtesy of: Antiques and the Arts

Doris Lee was a Depression-era artist that had all but been forgotten until a recent retrospective titled, “Simple Pleasure: The Art of Doris Lee”. The show recently began a nationwide two-year tour. As a painter and illustrator, Lee’s style was a mixture of folk art and Modernism. Like many female artists of the time, she fell into obscurity when the style of Abstract Expressionism took over.

During her career, Lee was featured at a number of prominent galleries and sold works to top museums; she also painted three murals for the Works Progress Administration. Life Magazine sent Lee around the world to work as an artist-correspondent which was an impressive assignment for a woman at that time. Finally, she produced art for major advertising campaigns… that art would win some awards for Lee.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Noel Allum

Throughout her career, Lee remained committed to figural painting and representational art. Even as Abstraction was growing in popularity, and critics thought that she should make more serious art with “more serious themes,” Lee continued to infuse humor into her work. Confident and fearless, Lee took on commercial projects without fear of being negatively judged. Staying true to her style, Lee was never sour to Abstraction and its practitioners; in fact, she was friends with many of those artists… sharing mutual influences.

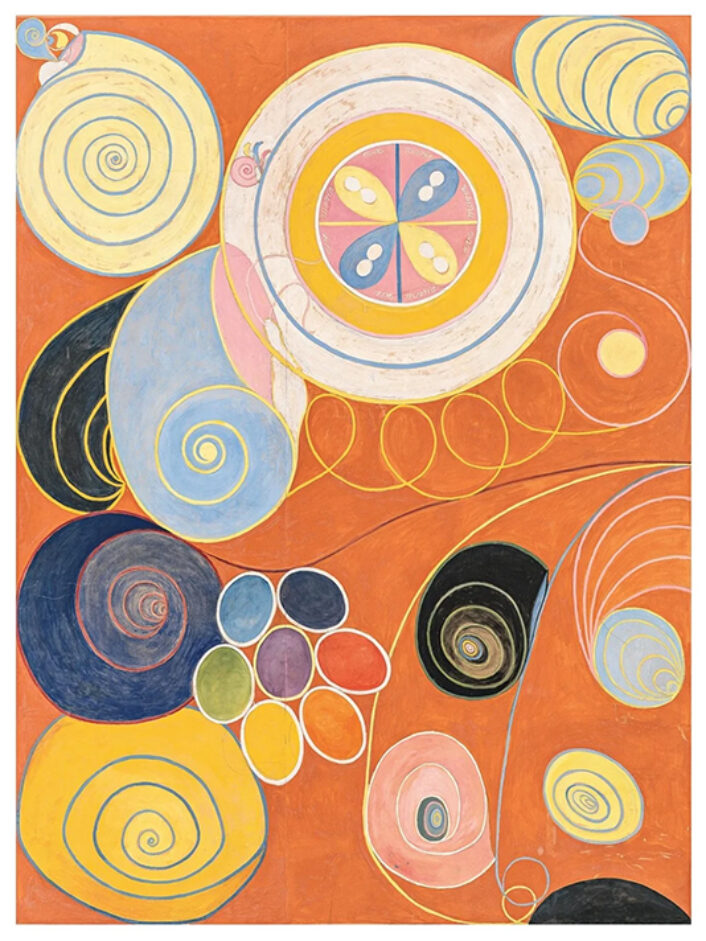

Even when Lee created her own illustrations of non-objective art (at both the beginning and the end of her career), her work differed greatly from her counterparts’. Courtesy of Antiques and the Arts, “There is a lightness and a brightness to her paintings, a sense of simplicity and joy. It is ironic that this quality of her work, which was enormously popular and critically acclaimed when it was created, has come to be seen as out of touch with her times.”

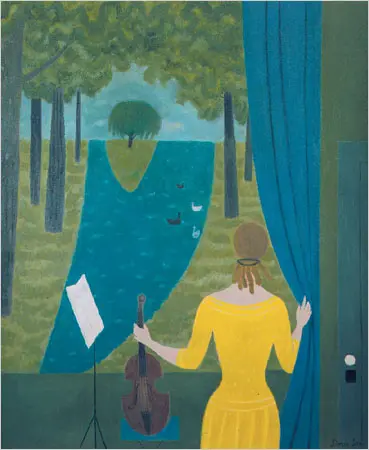

“The View, Woodstock,” 1946. Oil on canvas from the John and Susan Horseman Collection of American Art.

Dimensions are: 27.5″ x 44″

Image courtesy of: Citibank Private Bank

Lee was born in Illinois to a father who was a banker and a mother who was a schoolteacher. As a teenager, she was sent to boarding school for some discipline. The self-proclaimed “tomboy” was known to skip classes and rebel against her “normal” surroundings. Lee graduated with a degree in philosophy and went on to marry Russell Lee. At the time, Russell Lee was well on his way to becoming an acclaimed photographer for the Farm Security Administration. This marriage was short lived and soon, Lee became quite friendly with Arnold Blanch, a realist painter with whom she studied in San Francisco.

Lee moved to Woodstock, New York where she quickly established herself in the Woodstock Artist’s Community; the progressive location was perfect for the outspoken artist. Even though her work never seemed overtly political, she was active in combatting the time’s inequities against women. Courtesy of an article for The New York Times, Lee was quoted in a talk from 1951 that was titled, “Women as Artists, that it was “stupid” that young women were taught to find husbands, and told the audience, “We cannot afford to neglect or discourage any talent because of the artificial barriers of race, class, or sex.”

“Grapefruit Still Life,” 1950. Oil on canvas.

Dimensions are: 16″ x 20″

The bowl of grapefruit sits on a wooden column… “in perfect equilibrium between abstraction and figuration, folk art, and modernism. Lee expertly filters such motifs through a stylized, near-geometric pattern – the grapefruit bowl hovers in mid-air while leaves dance in the background as if part of a patterned wallpaper.”

Image courtesy of: Citibank Private Bank

The simple lines, frontal views, and flat colors portrayed Lee’s (courtesy of Citibank Private Bank), “deliberate application of both folk and modernist art approaches, such as Cubism and Fauvism.” She was a master at honoring everyday items; oftentimes highlighting their “basic” form and texture.

Lee’s rise with the American Scene painters was greatly accelerated thanks to the Depression; the movement pivoted against European modernism to develop a completely “American” art form. It was all about “Made in America,” and American customs, ideals, and future aspirations.

From the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Doris Lee circa 1935.

Image courtesy of: Hudson Valley One

“Simple Pleasure” was co-curated by Barbara L. Jones and Melissa Wolfe, Curators of American Art, Saint Louis Art Museum. The beautiful retrospective includes more than seventy works by Lee, spanning from the 1930’s through the 1960’s. The pieces come from both public and private collections; they include drawings, commissioned commercial designs in fabric and pottery, prints, and paintings. In addition to Greensburg, Pennsylvania, the show will travel to Davenport, Iowa, Vero Beach, Florida, and Memphis, Tennessee.

The scenes of rural life depicted by Lee were representative of life during that time and of an ideal that was sought after during the Depression era. She was perhaps one of the earliest female “commercial success stories.” Always an advocate for females, Lee portrayed women as happy and confident regardless of where they were. Both rural and urban women deserved happiness, Lee suggests. Emily Lenz, director and partner at D. Wigmore said about Lee, “She makes no apologies for her women and their joy, which I think shows a great deal of liberation.” Lee remained feisty as this example shows… “I remember hearing one woman say, ‘The most wonderful thing a woman can create is her family and home,'” she recounted. Her rebuttal “and you’ll never know the feeling of being an artist.” We love that!