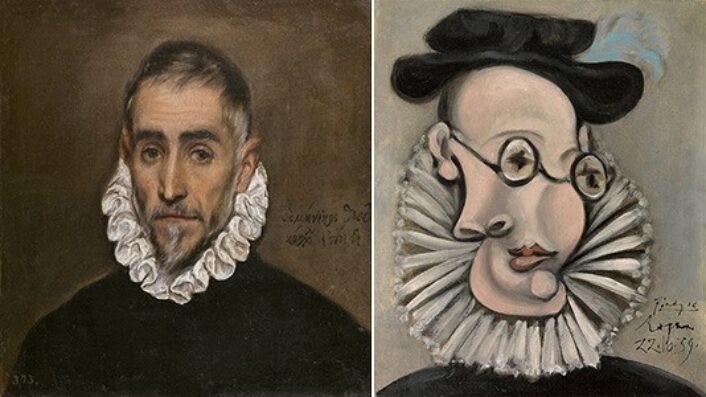

Fine Art

For the first time in 262 years…

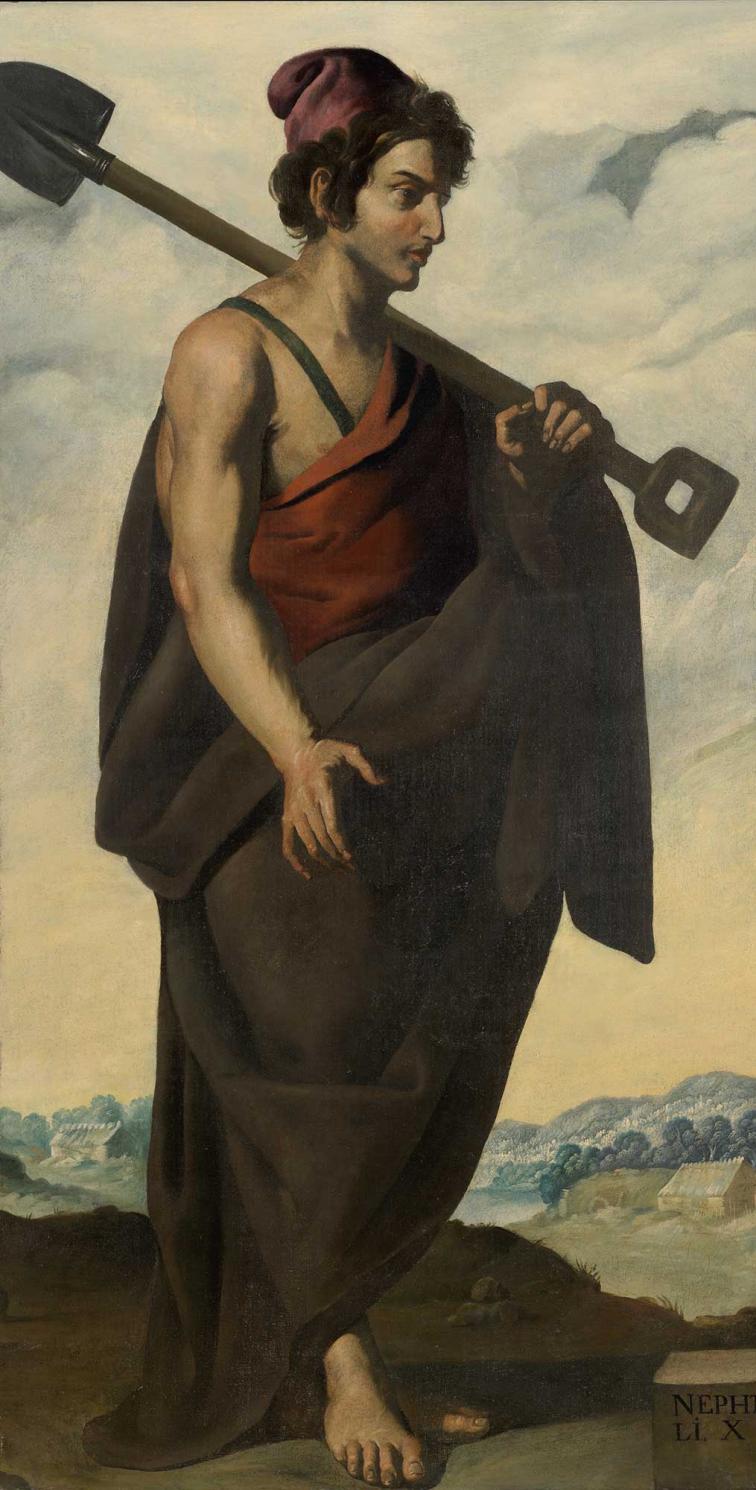

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), Jacob, from the series Jacob and his Twelve Sons, circa 1640–1645. Oil on canvas, 79 ⅛ by 40 ⅛ inches. Image courtesy of: The Magazine Antiques, photographed by: Robert LaPrelle

Art historians know that the 1590’s were known for the births of many very important artists… among them Diego Velazquez, Guercino and… Francisco de Zurbaran. Perhaps not as known as other, de Zurbaran is now the interesting subject of a new show at New York’s Frick Collection.

Now through April 22, 13 paintings that have been “hidden” from the public’s eye will be on display. The Spanish painter was known for his large sized pieces, the 13 painting currently on view is a cycle of seven-foot-tall religious paintings, dating from 1640-1650.

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), Figure #2, Reuben, circa 1640–1645. Oil on canvas, 78 ½ by 40 ½ inches. Image courtesy of: The Magazine Antiques, photographed by: Robert LaPrelle

In an ambitious collaboration with the Meadows Museum in Dallas and The Auckland Project, County Durham, England, The Frick Collection was able to organize an exhibition of Jacob and His Twelve Sons. This series of 13 paintings depict life-size figures from the Old Testament.

On loan from Auckland Castle, these 13 works have never before traveled to the United States. They were first presented at the Meadows Museum in the fall of 2017. The beauty Zurbaran’s iconography of Zurbarán’s is derived from the Blessings of Jacob in Chapter 49 of the Book of Genesis. This poem is quite significant to each of the 3 major religions. The writings tell that: “on his deathbed, Jacob called together his sons, who would become the founders of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. He bestowed on each a blessing, which foretold their destinies and those of their tribes. Jacob’s prophecies provide the basis for the manner in which the figures are represented in Zurbarán’s series”.

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), Naphtali, circa 1640–45. Oil on canvas, 78 1/2 x 40 5/8 inches. Image courtesy of: The Frick Collection

It is thought that these 13 paintings were created in Seville between 1640 and 1644 and that they were meant to be shipped to Latin America as Catholic propaganda for Spanish missionaries. Unfortunately, or fortunately, they never made it to their intended destination. Nothing was known about the works’ whereabouts until they turned up at auction in London in the 1720s.

In London, these paintings were purchased by a James Mendez, a Jewish merchant who owned them until his death in 1756. Upon his death, the paintings were snapped up in a posthumous property auction by the Bishop of Durham, Richard Trevor, a supporter of Jewish emancipation who displayed them at his official residence at Auckland Castle. The paintings remains there, privately for roughly 250 years.

Making their journey… 370 years later! The series as displayed at Auckland Castle in northern England. Image courtesy of: Auckland Castle

Zurbaran usually painted religious figures such as nuns, monks or still-lives. Most art historians believe that Zurbaran was self-taught; it is said that he often “borrowed” his compositions from other prints he’d found. Growing up in a humble household about 60 miles from Seville, he moved to the “big city” as a young adult to take advantage of a 3 year apprenticeship. Thereafter, he moved back to the countryside, married an agricultural official’s daughter and set up his shop.

Most of Zurbaran’s commissions came from the church. It was lucky that as a port city, Seville was quickly growing and thus; religious institutions found that they needed to be accessorized. For example, in 1822, Zurbaran returned to the city to paint 22 works for the convent of the Mercedarian order which is now Seville’s Museum of Fine Arts.

Auckland Castle outside of Durham in northern England is also known as the home of Prince Bishops. Image courtesy of: Auckland Castle

Some of the backstory… the gentleman who bought the paintings, Richard Trevor, was a connoisseur of art and architecture. He loved adorning his dining room with the 13 paintings and hoped that the series would heighten awareness for the discrimination that Jews in Europe faced. Some of the things Jewish people couldn’t do was receive university degrees, hold public office and become a citizen- unless they took Communion in the Anglican Church (this signified their conversion).

By displaying this series in his dining room, Trevor assured that his aristocratic and political visitors would be privy to some of the issues that these paintings might bring up. Clearly, this was a political statement being made in a “subtle” way.