Culture

Happy 100th birthday to the Phillips Collection

The well-preserved façade is home to state-of-the-art mechanicals, electrical, plumbing, climate, and security controls. These improvements are thanks to a substantial renovation that took place in 2018.

Image courtesy of: Traditional Buildings

The Phillips Collection, often called America’s first museum of modern art, was founded in 1921. It was opened by Duncan Phillips, the son of a Pittsburg window glass millionaire who died suddenly in 1917. The family encountered another tragedy the following year when Duncan’s older brother died from influenza. Along with his wife, Marjorie Acker Phillips, Duncan decided to honor his family members by turning the family home into a museum. He stayed committed to maintaining an intimate environment by displaying the collection in a series of rotating exhibitions.

This year, the Phillips Collection is turning 100 years old! The museum’s holdings have grown from 237 to almost 4,700. To this day, frequent visitors have been able to maintain a “personal connection” with the pieces they most enjoy.

Marjorie and Duncan Philips pictured in the Main Gallery, circa 1920.

Image courtesy of: Northwest Public Broadcasting

It is said that Phillips started this project because he wanted an outlet for his grief. Dorothy Kosiniski, the museum’s director since 2008 said recently (courtesy of an article with The Washington Post by Sebastian Smee), “Phillips wrote so poignantly about throwing himself into this project to save himself from deep despair after his father died and then his brother perished in the pandemic [the Spanish Flu]. He talked about finding salvation and solace, a way out of such profound grief, through art. We always alluded to the genesis story, but we never felt it like we do today.”

The Phillips’ were before their time, the museum was not just about collecting. From its inception, the exhibitions staged set a tone. It was the first museum to mount a solo exhibition by Milton Avery, John Marin, and Sam Gilliam; in addition, it was also the first American museum to give solo exhibitions to foreign artists, most notably Marc Chagall.

The Rothko Room, circa 1660-63.

Image courtesy of: Mapping Cultural Philanthropy

Some might draw parallels between the Phillips Collection and other major citys’ small museums that opened as a counterpart to big public institutions. New York City has the Frick Collection which “works” alongside the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Boston has the Isabella Stewart Garden Museum as a complement to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and Los Angeles has the Norton Simon as an answer to the Los Angeles Museum of Art. In D.C., both the National Gallery and the Phillips Collection occupy a prominent spot in the city’s important fine arts presentation.

Different from Henry Clay Frick and Isabella Stewart Gardner who were primarily interested in modern art, Phillips was curious, in fact infatuated, with his living contemporaries. Another unique aspect to the Phillips Collection is that unlike Frick and Gardner who wanted their institutions to remain stagnant, Philips said, “It must be kept a vital living place for enjoyment, and it must be given a sense of frequent rearrangement and new acquisitions.

‘The Migration Series, Panel no 23: The migration spread,” 1940-41. Casein tempera on hardboard. Dimensions are: 12″ x 18″

In 1942, Phillips purchased the thirty odd-numbered panels from Jacob Lawrence’s “Migration Series.” Today, this piece is seen as a American modern art masterpiece.

Image courtesy of: Jacob Lawrence The Migration Series

Since Kosinski took over in 2008, the scholar and published curator has made it a priority to honor the founders’ legacy. In 2015, she listened to her younger staff’s requests to become more “in tune” with the D.C. community. The museum set forth basic goals toward diversity and equality; and the collection strategy prioritized selecting a more diverse group of artists. Furthermore, the Phillips Collection decided that going forward, they would only offer paid internships and fellowships.

These are all things Kosiniski believes Duncan would have stood behind. She says, “Part of our history is that at a very early stage, Duncan Philips was buying works from African American artists. He invited them into the museum. He showed their works on the walls.”

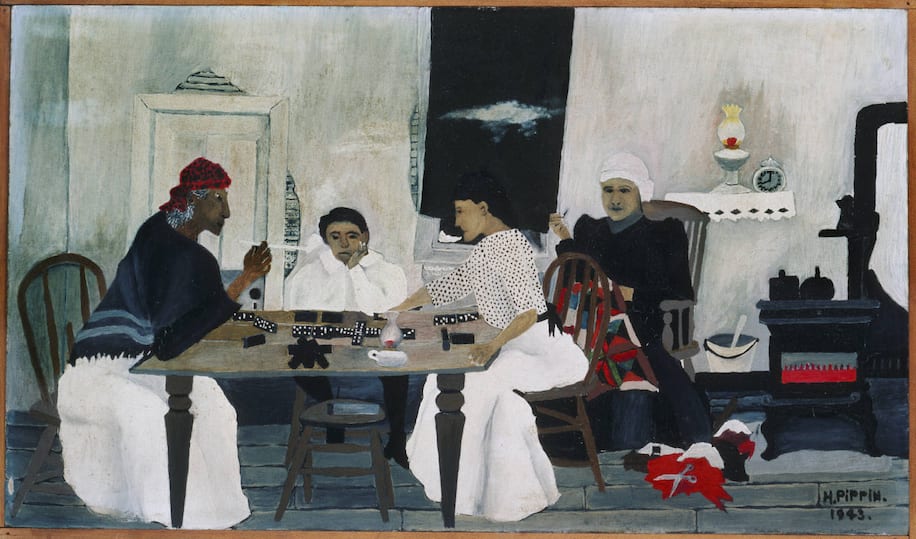

Purchased in 1943, “The Domino Players” was painted by Horace Pippin.

Image courtesy of: The Washington Post

Our favorite gallery sits on the mansion’s second floor…it is devoted to “family life.” Photographs of families by Bruce Davidson in addition to everyday scenes by Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard are part of this permanent collection.

The gallery’s categorization seems to have one theme in mind (courtesy of an article by The Washington Post by Philip Kennicott), “We are all human, all devoted to family, all equally committed to home and hearth. There are unities here, to be sure; but there are also essential differences, in scale, in wealth, in material comforts and in the subtleties of emphasis on what makes a house a home.”

With Phillips’ fortitude, The Phillips Collection lives into the next century. The founder made it easy for the subsequent generation to function within set parameters as long as this love for art and his passion for social issues remains honored.