Culture

Hidden beauty inside Mexico’s Michoacán churches

Apostle Santiago Church in Nurio.

Image courtesy of: World Monuments Fund

There is a long history behind Mexico’s Michoacán churches, many are located in an area that was ruled by kings since the 1300’s. A locale rich in natural resources; there is a lot of evidence pointing toward a culture that was rich in craftsmanship such as painters, carpenters, and stonemasons. It is said that this community thrived and was secondary in size and power only to the mighty Aztecs.

Unfortunately, the arrival of the Spanish brought more than mere disruption to the self-sufficient population of Michoacá; the Spanish also brought smallpox and other diseases that devastated the residents. Only three years later, the first Franciscan missionaries arrived… extending their influence through the lands. The foreigners rapidly established hospitals to provide medical care and lodging for both travelers and pastoral teachers. The hospitals, courtesy of a New York Times article by Michael Snyder, as quoted by the historian Carlos Paredes Martinez, “allowed the Indigenous people to continue performing traditional practices under the aegis of Christianity.”

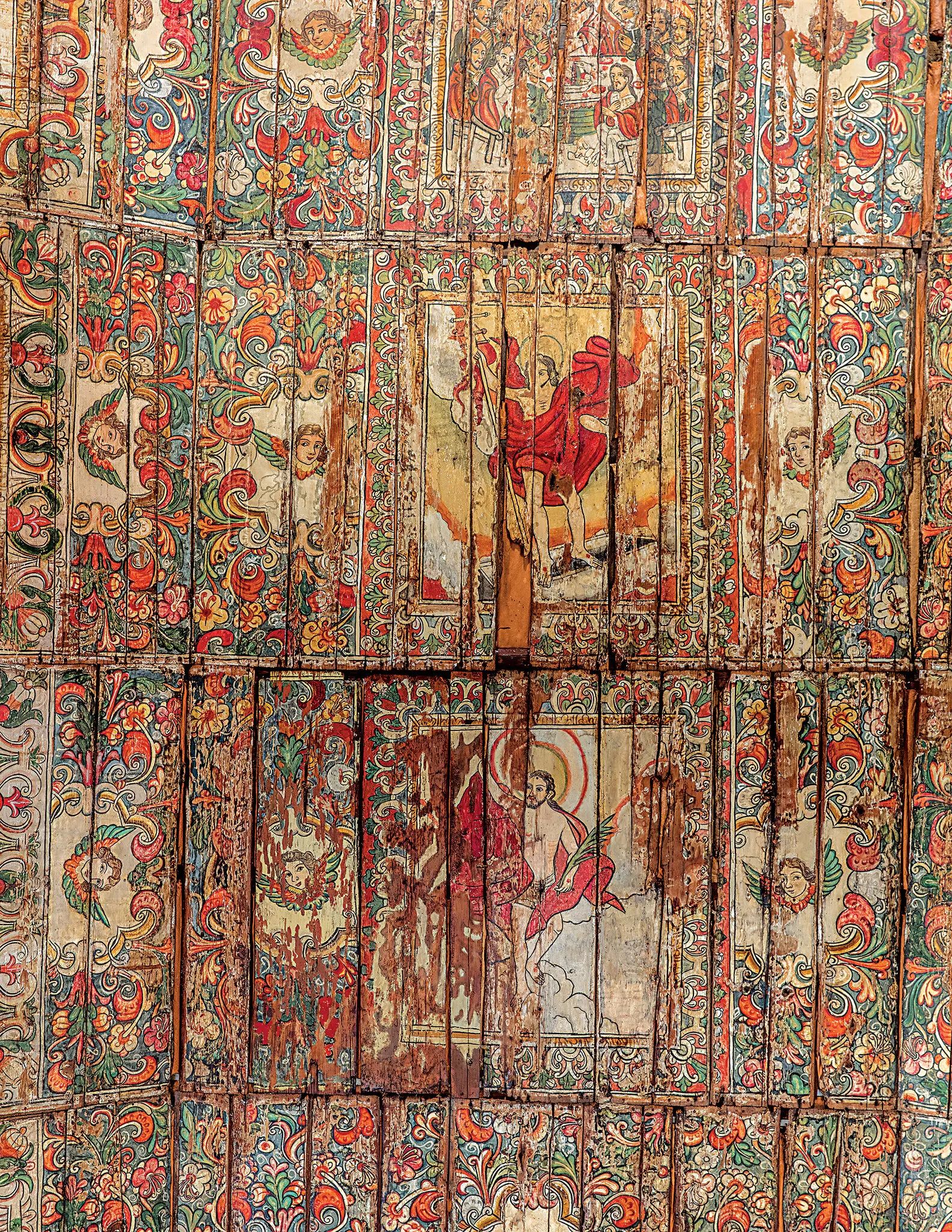

Decorative detailing inside Apostle Santiago Church.

Image courtesy of: World Monuments Fund

Specifically related to the Apostle Santiago Church, construction was initiated in order to form part of a huatápera, a hospital complex, by the Spanish Renaissance humanist and bishop of Michoacá, Vasco de Quiroga who was sent by the Spanish Crown to investigate the accusations of improper behavior against the conquistadors.

The stunning interior is full of elaborate detailing in a Mexican Baroque style (courtesy of World Monuments Fund), “which combined mudéjar carpentry and paintings done in the maque technique, a pre-Hispanic painting method that incorporates natural oils and minerals. The coffered ceiling and exposed wooden interior were beautifully painted; inspired by the philosopher Thomas More’s “Utopia,” that hoped to replicate his personal version of a utopian society where Indigenous people could reside in a community that is dictated by Catholicism.”

Churches in the region were extremely colorful, thanks to the Indigenous peoples’ use of pigments due to their knowledge of local plants and insects. In addition, the drop ceilings made from the region’s timber were gracefully supported by carved corbels that provided “ample space for places of worship to become illuminated manuscripts.”

The many figurative depictions of virgins, saints, angels, and martyrs that decorated the wooden ceilings were often inspired by European engravings and illustrated by Indigenous artists that came from Mexico City, the colonial capital. The Christian cosmology they depicted were different than anything previously seen, however it was a way to connect the present to the “previous world.”

Apostle Santiago Church in Nurio has a stone entrance with Corinthian columns. In Augustinian style, a Latin frieze above the door proclaims: House of God and the Gate of Heaven, and bears the date 1639.

Image courtesy of: Colonial Mexico

Sadly, many of these churches have not fared well. The last church was painted in the mid-19th century; around this time, the Mexican government passed a number of reforms to strip the church of power and property. Following the ten years of revolution, in 1920 “conflicts between the secular political establishment and church loyalists led to the closure of countless churches in central-western Mexico.

Over time, many Michoacán churches have been destroyed due to abandonment or insect infestation or the fragile mud-and-timber architecture. Even though the conservation of national treasures throughout Mexico has been ongoing since the 1970’s, the region’s remote location made investment in restoring the churches’ abundant glory a difficult task.

Angels alongside scenes of Jesus and Mary on the ceiling of a Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Stefan Ruiz

The feeling in this rural part of Mexico is that there should be a sense of urgency to restoring some of the country’s oldest monuments. However similar to so many other places in the world, politics play a part in continued bureaucracy leading to stagnation. Demetrio Alejo Rubio, Nurio’s second mayor, said, “The important thing now is to recuperate our civic, historic, and cultural tradition.” Yes, indeed.