Fine Art

I spy…

Bruegel’s “Dutte Griet” has been restored especially for this exhibition.

Image courtesy of: Art Newspaper

What happens when you combine art and present-day technology? Interestingly enough, new technology is allowing researchers to uncover the stories that lie beneath the surface of some of the world’s most sacred and priceless artwork.

A project called, “Inside Bruegel” from Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum allows us to pull up and investigate layers of art underneath Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s works. This exhibition featured 87 of the master’s works; and allowed visitors to follow Bruegel’s creative process.

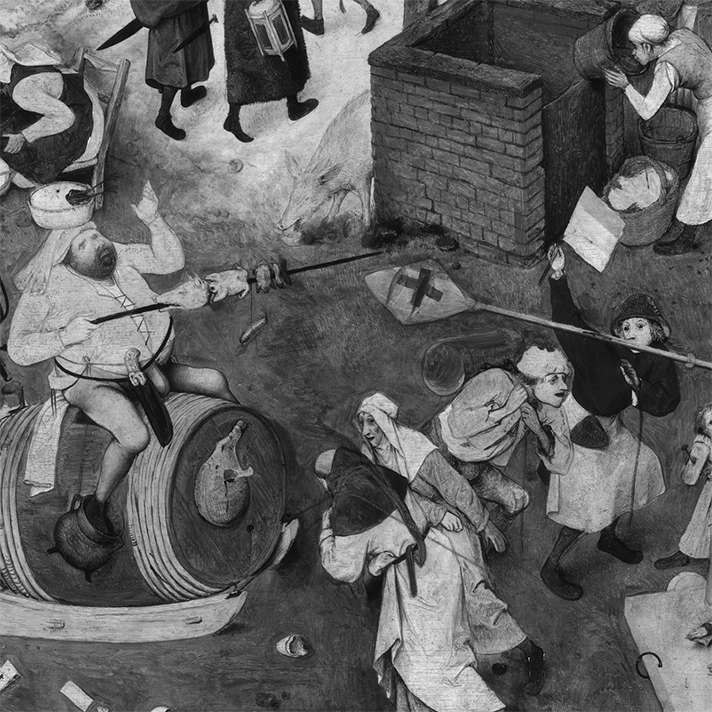

“The Battle Between Carnival and Lent”, 1559. 118 cm x 164.5 cm. Oil on oak wood.

A true Flemish piece by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, an Old Master painter who was relatively elusive.

Image courtesy of: Musee Historique Environment Urbain

What’s amazing is that you can actually follow the intricate creative process…

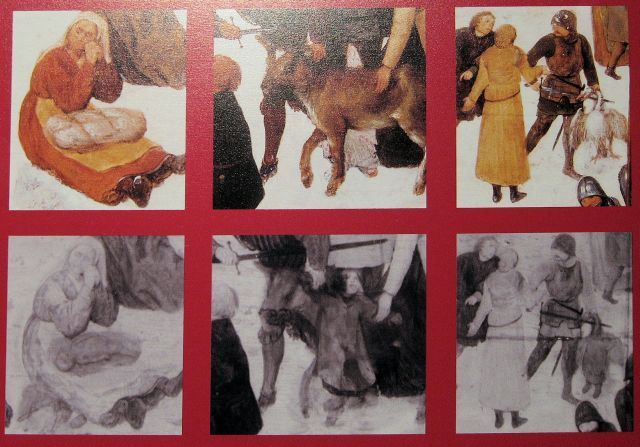

Looking at the first drafts with the help of x-ray photography, you can clearly see a corpse inside a cart that an old lady is dragging. Then, there is another corpse on the ground with the face turned to see the viewer. This deceased person is laying very close to a gravely ill looking child.

Now the final version of the painting is missing these morbid elements: the corpse in the cart is now a bit of brown paint and the body on the ground is covered with a white piece of fabric.

New imaging technology helps us get insight into this puzzle by pulling apart the painting’s layers. Fascinating!

The exhibition marks the 450th anniversary of Bruegel’s death. Bringing together 87 pieces (two-thirds of his work), there are 28 original paintings, 26 drawings, and 33 prints.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times

The amazing detailed works created by Bruegel always appear chaotic. It’s no surprise then, that he changed his mind multiple times during his diligent process. Interestingly enough, Bruegel was ahead of his times in that he mocked religious themes and religious superiors. He also minimized death and destruction; and made peasants, rather than noblemen, the story’s central figures.

It has been verified that on his death-bed, Bruegel asked his wife to burn his drawings for fear that they might be too controversial. Ron Spronk, an Art History professor and one of the exhibition’s four curators has said, “One of the things that art historians debate quite seriously is to what level Bruegel was criticizing the government of that day. Those kinds of questions are still debated today.”

The finished product of ” The Battle Between Carnival and Lent”.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times

The chubby man holding a pig on a stick is jostling with the man holding the two fish on the paddle. However, in the drawing, the paddle actually features a cross.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times

Similar to other 16-century Old Masters, Bruegel constructed his paintings meticulously on wood panel. As layer upon layer were laid down, changes occurred. Initially, Bruegel started with a light-colored foundational surface made of chalk and animal glue. It is on this foundation that he would sketch out his thoughts. Oil was used after his primary process was completed.

Interpreting “The Battle Between Carnival and Lent”, the villagers are separated by their activity: the ones who went to the festival are on one side and the religious observers of Lent are on the other side. Two fish are at the center of the piece; perhaps with a deeper purpose? Through infrared rays, we can see that rather than two fish, Bruegel painted a cross. Later, the cross was removed and fish were added. Although the logical expatiation is that fish is often served during Lent, fish are also symbols of Christ. This switch can be interpreted in a variety of ways and that is what’s so fascinating.

Image courtesy of: Gerry Company WordPress

Perhaps one of the world’s most famous paintings, “Massacre of the Innocents” is another perfect example of the alterations that Breugel made. Originally presenting the slaughter of children, this was a blatant portrayal of the Spanish Inquisition atrocities in the Netherlands. Historians believe that this might have been “too much to handle”, and during the 17th or 18th-century, someone replaced all the massacred children with images of murdered farm animals.

Art historian, Robert L Bonn sums Breugel up perfectly, “To look at almost any Bruegel painting is to be transported back to life as it was known more than four centuries ago. But that’s not all. With Bruegel, a second deeper look invariably reveals a certain ‘something more’. This ‘something more’ varies from painting to painting. It may be secular or religious. It may be a proverb, a moral, a philosophical dilemma or a social myth. Whatever it is, I have often found it to be strikingly modern.”