Culture

James Kerwin’s “Abandoned Places” photographed

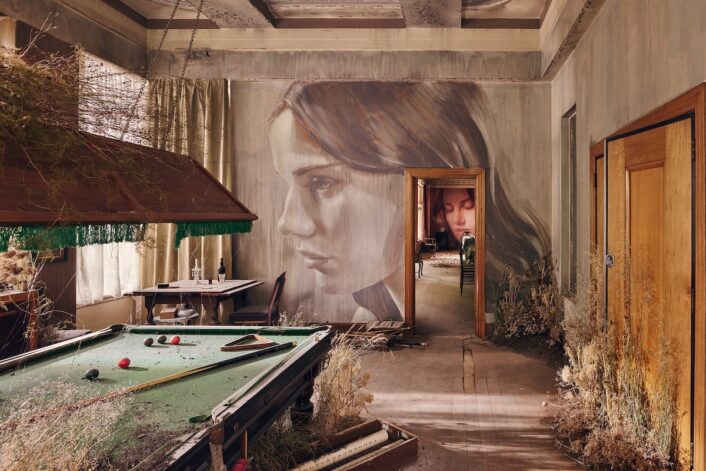

From 2019’s “A Paradise Lost” series; specifically, a mansion from the “Orange and Teal” collection.

Image courtesy of: Luxeo

James Kerwin is an English photographer… a visual storyteller that explores the world’s abandoned churches and buildings. The self-taught photographer has captured some of the world’s most glorious neglected ruins and relics throughout the world, often in remote locales.

Kerwin has a way of pinpointing the stillness that these locations possess. Courtesy of My Modern Met, “With a studied eye for composition and color, Kerwin creates beautiful documents of the texturally rich but criminally underappreciated corners of the world.”

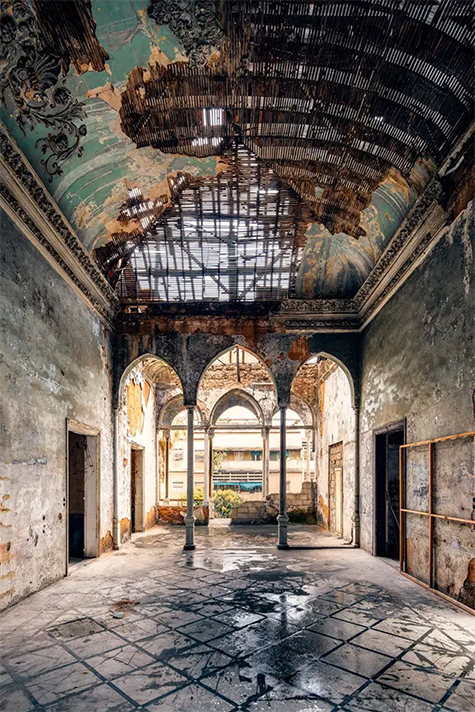

“Paris by Design,” a mansion with ceiling details in full effect.

Image courtesy of: The National News

Three years ago, Kerwin took it upon himself to capture Lebanon’s history of bombardment in “A Paradise Lost.” As one of the world’s oldest cities, dating back over 5,000 years, the city has a long list of conquests and triumphs. Once called “the Paris of the Middle East” due to its French-colonial architecture and sophistication, Beirut was a relatively stable, international city that brought in tourist galore.

Sadly, the stunning city suffered severe years of unrest beginning with the civil war that broke out in 1975. In addition, throughout the 1980s, the city’s Christian and Islamic sides had numerous conflicts. Finally, in 2006, the war with Israel resulted in further consequences of demise.

“Triple Arcade.” Most often an external feature, the triple arcade also appears in interiors.

Image courtesy of: Architectural Digest

Kerwin considers himself an urban explorer; he is part of a growing group of photographers who document abandoned structures and present them in a new light. He says (courtesy of The Spaces), “There’s a sad side of such buildings being left to rot but, in many cases, an explorer’s photos can lead to a building being purchased and saved,’ he says. ‘It’s not all doom and gloom!”

It makes sense that Kerwin, along with his fellow explorers, is particularly protective of the architectural finds he chronicles. He spends a lot of time researching exactly which locations would provide him with the most touching images. Kerwin keeps his locations a secret, he says, “Giving away the location leaves these buildings vulnerable to graffiti, vandalism and even fire.”

Inside a home in Al Madam, an inland ghost town of the Emirate of Sharjah in the UAE.

To complete “Uninhabited,” Kerwin still needs to photograph a place in both South America and the Caribbean.

Image courtesy of: Stir World

Prior to the pandemic, Kerwin began a series called “Uninhabited” that drew him to remote locations. The ghost town of Sperrgebiet in the Namib Desert was a place once populated with miners working in the local diamond mines. However, the area is now deserted and the buildings’ only occupant is a “sea of sand.”

In deciding which lost villages and towns to photograph, Kerwin spent a lot of time surveying maps. He looked for one or two places on each continent for “Uninhabited.” Thus far, he captured Europe’s Ukraine, Africa’s Namibia, and the Middle East’s United Arab Emirates.

Many of the thirty buildings photographed were damaged in 2020 when 2,750 tons of stored ammonium nitrate detonated. Improperly stored at Beirut’s port, this triggered a fire in the foreword factory next door… coincidently crippling many of the neighboring heritage buildings.

Image courtesy of: Africa Pearl

Most recently, Kerwin debuted a number of Lebanese ceilings in varying states of ruin. He wanted to showcase the beauty of this local architecture which is hidden in the rotting ceilings, some of which date back thirty years. Called Baghdadi ceilings, the intricate ceilings fill many of the homes throughout Lebanon. Baghdadi is the name given to the traditional “false” ceilings used in heritage buildings. Those ceilings are made of wooden strips (called lath) and covered in plaster before they are paintings and sometimes embellished with frescos, artwork, or additional moldings.