Architecture

Joseph Stella and the Brooklyn Bridge

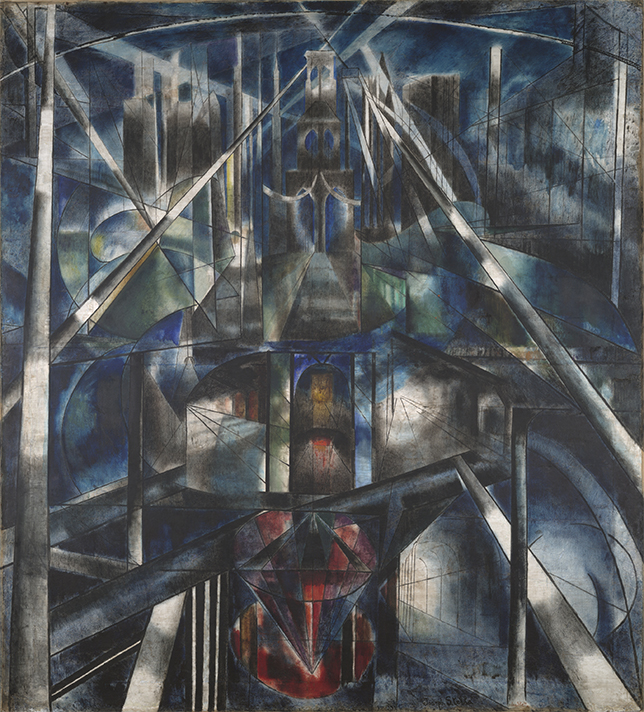

“Brooklyn Bridge”, oil on canvas, 1919-20. Yale University Art Gallery.

Dimensions are: 215.3 cm x 194.6 cm.

Image courtesy of: Wikimedia Commons

When Joseph Stella arrived in New York in 1896, he was already in love with the vibrant city which differed substantially from where he grew up in Italy. During his childhood in an Italian mountain village not far from Naples, his imagination was fueled by reading Edgar Allan Poe and Walt Whitman. He was especially intrigued by the large number of vertical buildings and urban architecture.

Stella arrived to the United States at the age of 18 in hopes of following in his physician brother’s footsteps. Quickly frustrated with the discipline of medicine, he decided that his future lay with art.

“Printer’s Row As It Stood in the Spring of 1908″.

Dimensions are: 11 ¾” x 18 ½”

About Pittsburg, Stella said, “I was greatly impressed by Pittsburgh. It was a real revelation. Often shrouded by fog and smoke, her black mysterious mass–cut in the middle by the fantastic tortuous Allegheny River and like a battlefield, ever pulsating, throbbing with the innumerable explosions of its steel mills–was like the stunning realization of some of the most stirring infernal regions sung by Dante.”

Image courtesy of: Christie’s

His teachers called him a gifted pupil and urged him to learn from the “great realists of history.” In 1907, a publication commissioned him to illustrate the recent mining disaster in West Virginia and the following year the same publication asked him to draw the industrial city of Pittsburgh. Quickly, Stella’s prominence was cemented as an academic realist.

However, a few years later he took a trip to Paris and spent time with members of the Parisian avant-garde. It was here that he began to appreciate the radical art of his contemporaries. Upon arriving back in the United States, he instantly mastered an advanced and revolutionary abstract style. He was able to magically capture the excitement and intrigue of America’s quickly growing urban industrial environment.

A pixelated version of “Brooklyn Bridge.”

Image courtesy of: Pixels

Ever since he first arrived in America, Stella was fascinated by the Brooklyn Bridge. However, when he moved to Brooklyn in 1916 and lived in its shadow, he decided it was time to immortalize the stunning architectural feat on paper. He saw the bridge through the eyes of a small boy from a small Italian village. To Stella, the sheer amount of steel and electricity that made up this majestic feature was fascinating and spell-binding. In a 1929 essay about the bridge he said, “the shrine containing all the efforts of the new civilization of AMERICA…. Many nights I stood on the bridge- and in the middle alone…. I felt deeply moved, as if on the threshold of a new religion or in the presence of a new DIVINITY.”

Stella used small intersecting planes and patch-like brushwork which resembled Cubism and Futurism. Fragmentation is evident throughout, and the stone pillars, steel cables and elevated pedestrian walkways work together to emphasize the massiveness of this industrial building.

Stella’s strong draftsmanship is evident in many of his architectural interpretations.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Not a particularly religious man, Stella’s vision depicts the bridge as something similar to a modern-day altar, a place that holds spiritual significance. The massive cables give reference to the pointed arches of Gothic architecture and the rich, jewel-toned palette is reminiscent of strained glass windows in a Gothic cathedral.

“The Voice of the City of New York Interpreted; The Skyscrapers” (The Prow)

Image courtesy of: 1000 Museums

It is clear that Stella never decided whether or not modern industry was a positive or a negative. The benefits that came out of the Industrial Revolution came at a cost for thousands of people. Stella saw both sides of the coin… however that did not have an effect on the admiration he had for the architecture that was sprouting around New York City at that time.