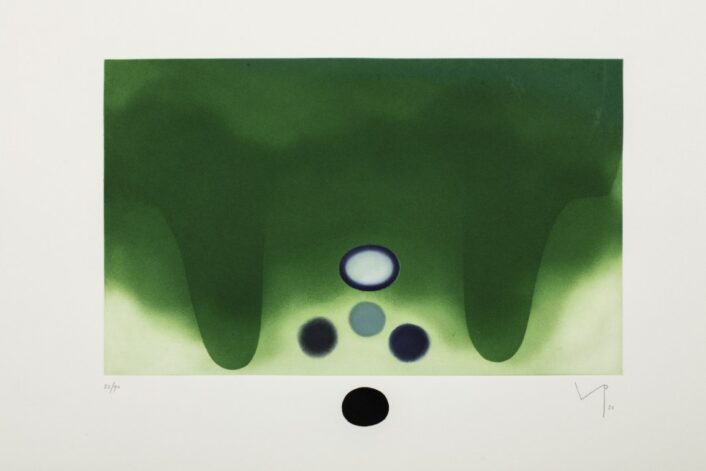

Fine Art

Lee Mullican

“Untitled,” 1949 from James Cohan Gallery in New York City.

Image courtesy of: ArtNews

Born in 1919 in a small town in Oklahoma, Lee Mullican was interested in art even as a young child. He studied at Kansas City Art Institute and followed his academics with a wartime appointment in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers where he served as a topographical draftsman. Fueling his creativity as best he could in the Army, Mullican captured aerial photographs of vegetation, rivers, and roads. Coincidently, the visions of the dense patterning below would impact his paintings for decades.

For more than fifty years, Mullican resided in California; initially, he moved to San Francisco where he exhibited his work with well-known artists such as Wolfgang Paalen. Five years later, the artist moved to Los Angeles where he began mentoring many young artists at public schools and becoming a known pillar of the Los Angeles art community.

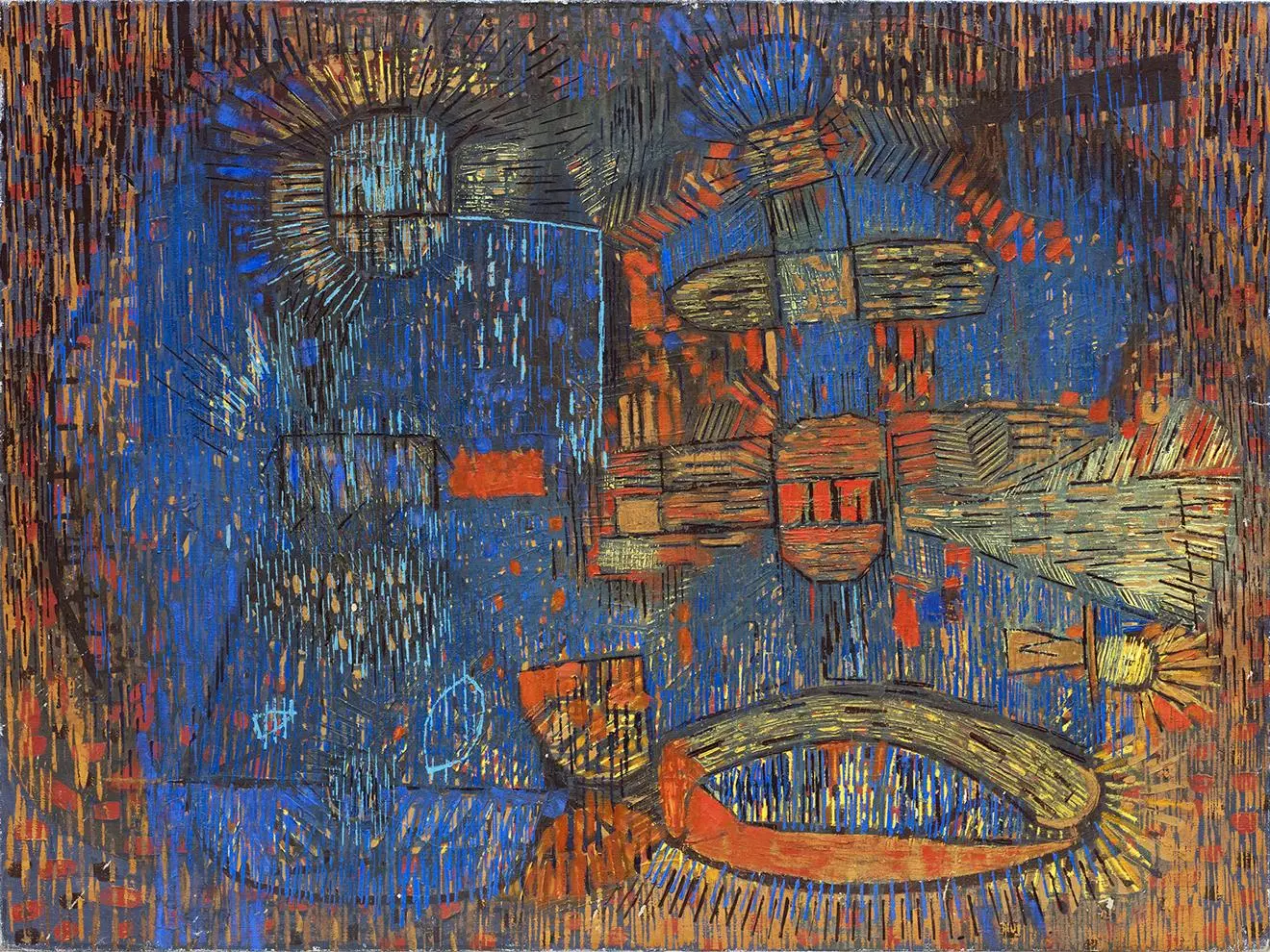

“California Landscape,” 1958. Oil on canvas, courtesy of Randall and Lara Kaplan.

Image courtesy of: Grey Art Gallery NYU

Mullican’s drawings and paintings evolved tremendously over five decades; however he would continue to draw inspiration from the natural world for the entire span of his career. The artist (courtesy of Galleries Now) “developed a practice of mapping both a quasi-mystical internal landscape and an external topography.”

Two aspects that remained present in all of his paintings were aerial and the omniscient. Different from the traditional sense, Mullican’s landscapes were expansive and vast, rather than pinpointed on a particular piece of land or feature. In 1953, Mullican explained, “I am concerned with the essence of nature; its behavior, its contour and exploitation, as in the discovery of a new planet with its phases of light, growth, weather; of a world solid in its seasons—brittle in winter—transparent in summer; a vista built for meditation—the air being important—shock being replaced by contemplation and a radiation of a wave and a plain …”

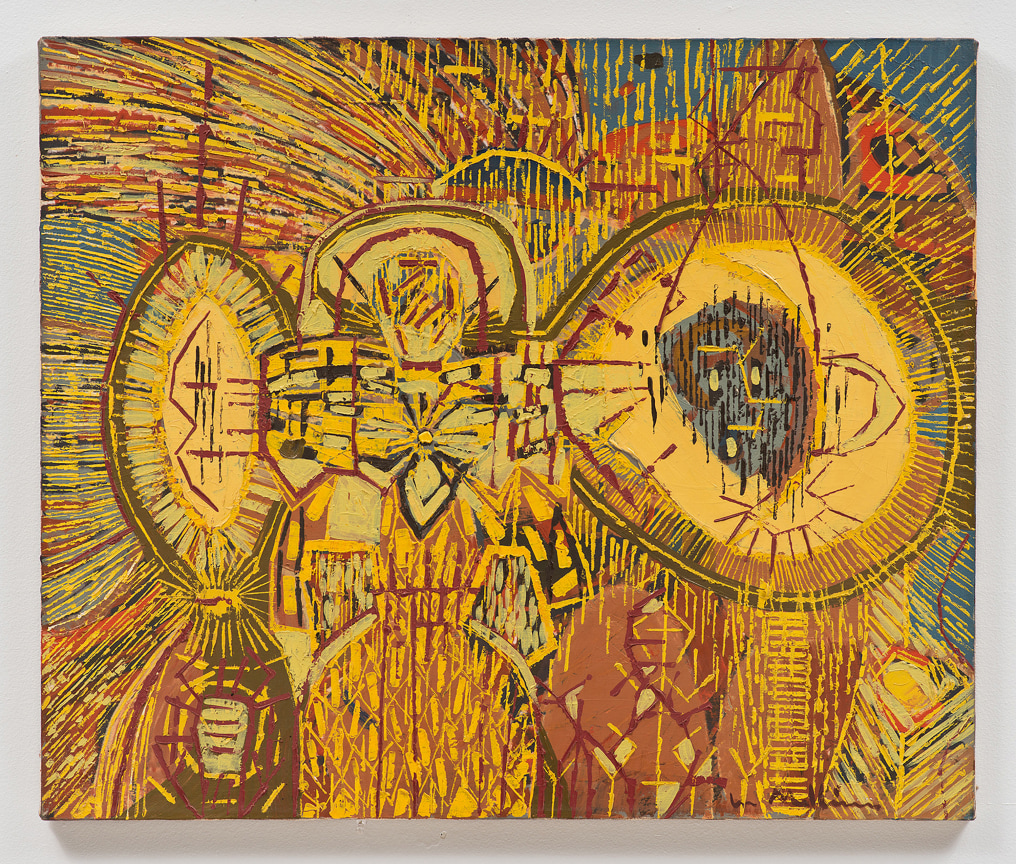

“The Nest Revived,” 1948. Oil on canvas.

Image courtesy of: James Cohan

Mullican differed from the Abstract Expressionist paintings on the East Coast because he garnered inspiration from non-Western sources, specifically Zen Buddhism. California living also exposed the artist to Surrealism’s automation and to tantric art found in India. For his entire career, Mullican was also fascinated with concepts of outer and inner-space.

In addition, Native American and pre-Columbian cultures, mysticism, and physics brought a sense of the supernatural to many of Mullican’s paintings… and revealed his (courtesy of James Cohan) “belief in the spiritual dimension of abstraction.”

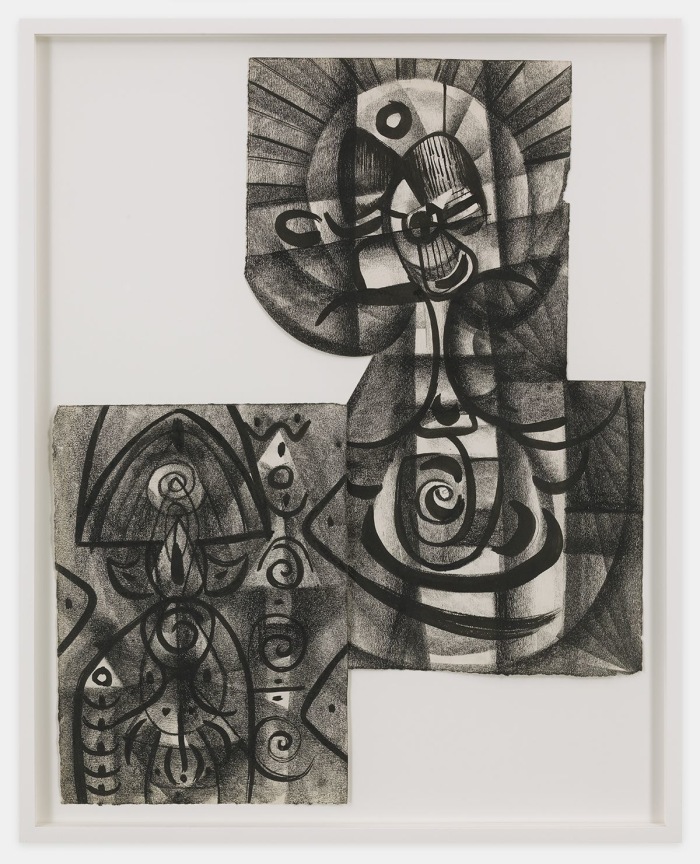

“Untitled,” 1950. Crayon and ink on paper.

Image courtesy of: James Cohan

Mullican split his time between Los Angeles and Taos, New Mexico… where he was clearly inspired by the artistic community’s vibe. Mullican’s focus on finding different meanings to formal problems through color, mark making, and composition inspired him to invent a method of applying paint to the canvas via the thin edge of a printer’s knife. This revealed a build-up of fine lines on the surface, the technique was referred to as “striation.”

For Mullican, he hoped that his viewers would see that this new style “excited” the canvas’s surface… allowing the paintings to feel alive. In addition, the color choices had definite meanings: the yellows referred to the golden lights of a radiating cosmos and the earthly colors: browns, deep reds, and violets, conjured up images of magical mountains inspired by (courtesy of Galleries Now) “walks in landscapes that appeared from the depths of the mind.”

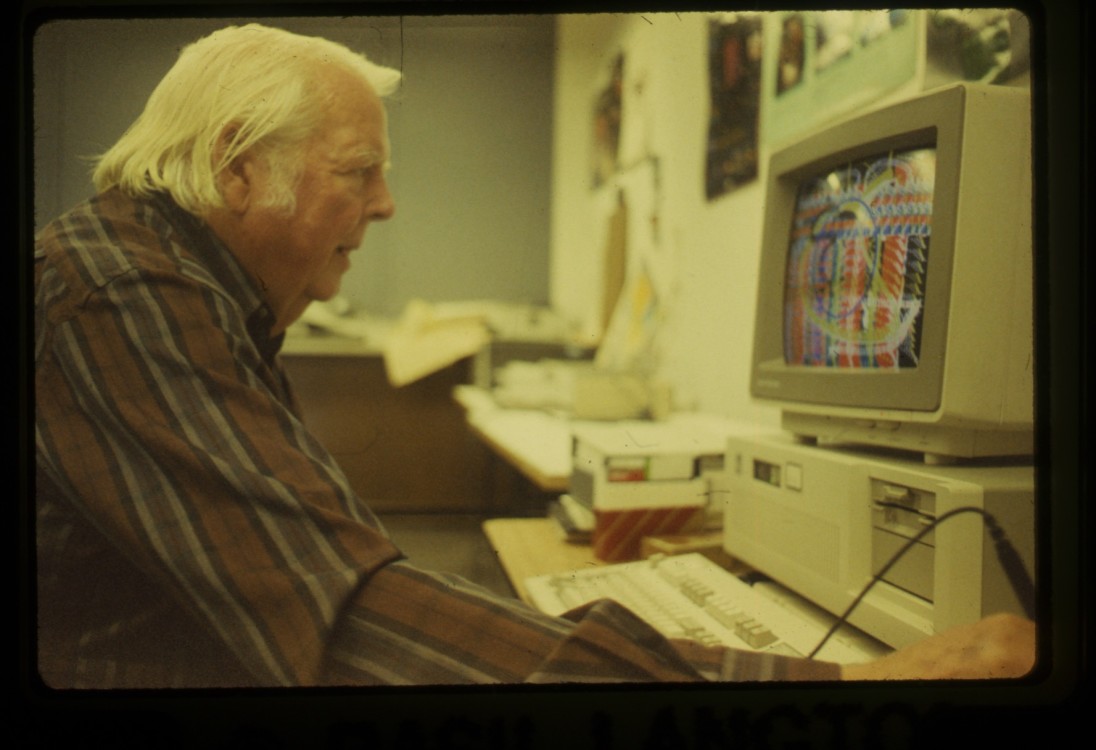

Mullican at UCLA in 1987.

Image courtesy of: Versiart, photographed by: Basil Langton

Always curious and always experimenting, these traits continued for the entirety of Mullican’s career. In the mid-1980s, the painter was one of the first to pioneer digital works. Certainly ahead of his time, Mullican was instrumental in bringing art and technology together at a time when the “digital age” was just a fantasy.

At 67, Mullian began to work with the Program for Technology in the Arts at UCLA. His agenda was simple: to explore how his unique style of painting could be translated to a digital realm. Mullican seemed to already know what would happen… the digital works would feel as though they were jumping off the screen. Mullican’s rich colors and repetitive patterns forced the viewer to keep looking at the screen.

It is safe to say that Mullican was indeed a pioneer; he understood the issues that computer programs produced and realized the unpredictable nature that existed in digital art. However his calm demeanor pushed through as evident by this quote (courtesy of Versiart), “I found that beyond what one thought, the computer as being hard-lined, analytical, and predictable, it was indeed a medium fueled with the automatic, enabled by chance, and accident, discovery of new ways of making imagery.” Thank you Lee Mullican!