Fine Art

Marie Cuttoli’s fabled tapestries

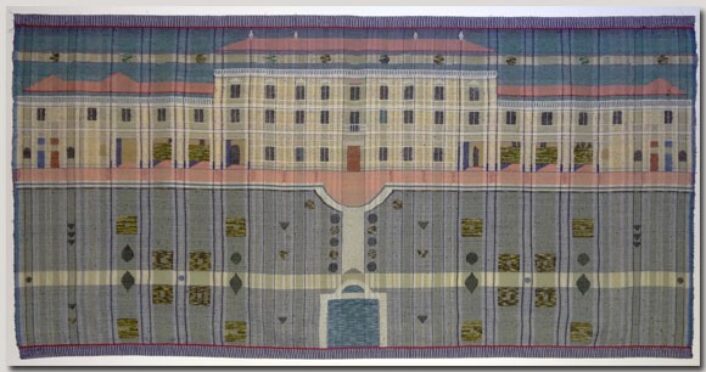

“Marie Cuttoli” by the Swiss architect-artist, 1936. Wool and silk. On loan from Foundation Le Corbusier, Paris.

In this cartoon for the tapestry, the artist paints a nude woman whose head resembles a caricature of Cuttoli with a boat and a top. However, when translated into wool and silk, the figure feels rounder and more sensual and the look in Cuttoli’s eye is wilder.

Image courtesy of: The Philadelphia Inquirer

Marie Cuttoli is a name not super familiar to many within art circles; however, the collector and patron of French modern art is considered to be responsible for bringing the art of tapestry into the 20th-century. Cuttoli achieved this through her commissions to modern and Cubist painters. She was successful at collaborating with artists, dealers, and museum directors for the course of her long career, which began in 1920 and spanned 45 years.

Cindy Kang, the Barnes Foundation curator behind a new exhibition titled, “Marie Cuttoli: The Modern Thread from Miro to Man Ray” said, “Tapestry was- at least in French art history- such a prestigious medium. It was in decline, but is still had the historic tradition.”

“Ocoteas” by Jean Lurcat, 1957. Aubusson tapestry woven by the Tabard workshop.

Dimensions are: 158 cm (height) x 218 cm (length)

Cuttoli hoped to revive this art form that was very popular during the Renaissance times.

Image courtesy of: La Tapisserie La Tapisserie

Cuttoli grew up outside of Paris, in a small and rural village. At the age of sixteen, she moved to Paris where she was exposed to the latest trends in both modern fashion and artistic production. She soon married a wealthy Algeria-born politician and art collector, Paul Cuttoli. Her marriage allowed her to have proper funds and adequate support to begin a small Cubist art collection.

However, Cuttoli was set on reviving the dying art of tapestry. During the depression, she spent her time between Paris and Setif, Algeria where she set up a workshop to teach local women the art of tapestry weaving. She sold the works at established Parisian production houses and displayed them at the Maison Myrbor- her design studio and exhibition space.

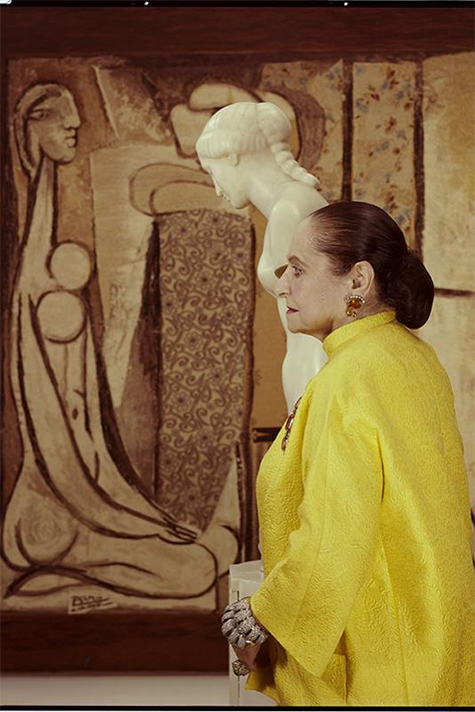

Helena Rubenstein in front of Pablo Picasso’s tapestry, “Secrets.” Rubenstein was a prolific modern art collector who found a special liking to tapestries.

Image courtesy of: Forbes

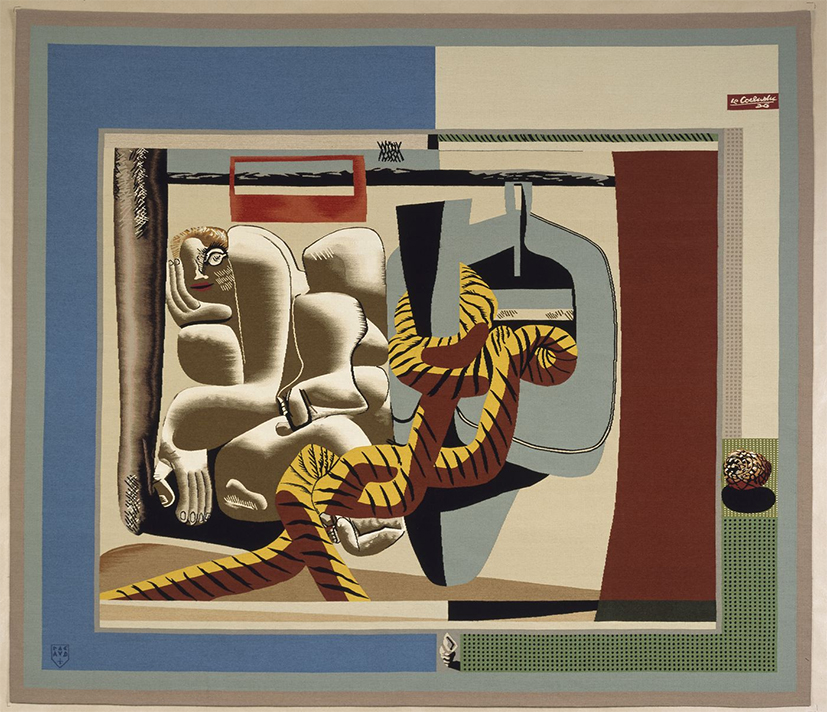

Unique to Cuttoli was that she befriended most of the artists whose work she commissioned. Years before she asked Picasso to design a tapestry, his work hung in her home. The two collaborated several times in the 1920s and 1930s, solidifying their relationship as lifelong friends and business partners. Prolific in producing cartoons for tapestries, Picasso produced a cartoon of “Minotaure” (1928) which was woven in 1935 and his large-scale “Women at Their Toilette” (1938) that was the basis for a tapestry woven at Gobelins in the 1950s.

Kang said, “The fact that she was a collector and a gallerist was instrumental to her being able to do this project at all. That’s how she established the relationship; that’s how she established trust.”

Alexander Calder tapestries at Omer Tiroche Contemporary Art, London in 2015.

Image courtesy of: Artsy

Cuttoli’s entrance into fabrics occurred in the early 1920’s when she started a fashion line and commissioned designs by artists. Soon after, Cuttoli added rugs to her inventory, enlisting artists that she personally collected to design small carpets that would look just as impressive on the walls as on the floors.

In 1926, Cuttoli rebranded herself as Galerie Myrbor and she began hosting exhibitions that featured young artists. Within just a few years, Cuttoli became focused on rugs and contemporary art exhibitions. In quick progression, floor to wall to woven murals happened. A new decade saw bigger accomplishments for Cuttoli; she started commissioning designs from artists like Rousault, Man Ray, and Henri Matisse.

Historically, large-scale woven hangings were a luxury art form between the Middle Ages and through the Baroque era. Mostly seen in castles and cathedrals, kings, members of the clergy, and nobility were the only ones privy to these monumental artworks. Thankfully, Cuttoli’s 20th-century sensibility helped to revamp the often misunderstood and complicated medium.

A Miro tapestry at the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

Image courtesy of: Aubusson Tapestry

Full circle indeed… as one of Cuttoli’s most important American clients was Albert Barnes and this year, a Barnes Foundation exhibition traced Cuttoli’s pioneer career.

Dr. Albert C. Barnes was one of Cuttoli’s most vocal advocates and patrons. The founder of Philadelphia’s fabulous Barnes Foundation, he bought pieces by Picasso, Rouault, and Miró. These three selections are all presented in the exhibition even though Dr. Barnes had previously donated them to the people of France.

This year’s show was not the first American exhibition to feature Cuttoli. During World War II, there was a wartime showing which was considered as a gesture of solidarity with occupied France. The nationwide exposure helped to make the exiled Cuttoli more renowned in America than in her homeland of France.

Among the rich archival materials is a digitalized national radio broadcast of Dr. Barnes praising Cuttoli. In the same thread, Kang said about the trailblazing collector, “Marie Cuttoli was a trailblazing entrepreneur who breathed new life into the tradition of French tapestry and helped redefine what modern art could be in 20th century. It is exciting to shine a light on her impressive career and to present a new history of art that includes decoration as a serious endeavor of modernism here at the Barnes—especially given Dr. Barnes’s enthusiasm for Cuttoli and her work.”