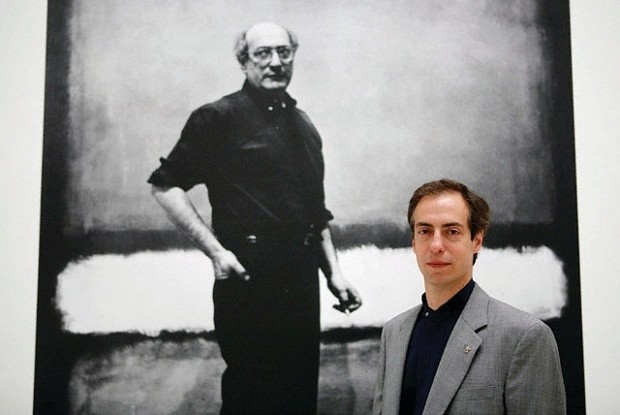

Rothko’s son Christopher Rothko, in front of a photograph of his father and one of his paintings.

Image courtesy of The Art Newspaper.

Last year Rothko’s son Christopher published a book, Extract from Mark Rothko: from the Inside Out, outlining his father’s inspiration and process. One of the most interesting pieces of the book is his exploration of Rothko’s obsession with Mozart. He was committed to creating the same grace that Mozart had achieved in music, in his paintings.

Here is one of our favorite excerpts from the book and more can be found in the Art Newspaper article.

I focus here on Mozart, the alpha and omega for Rothko. Certainly not the most obscure of composers, but why so lionised by my father with such an exclusive, even monogamous, zeal? What is it about Mozart’s music that so appealed to Rothko’s soul? Certainly there are few parallels in their biographies. Mozart the wunderkind burst fully formed from his father’s thigh, composed large-scale works at the age of five, toured all of Europe as a phenomenon, only to see his fame fade as he grew to manhood. This was hardly Rothko’s trajectory (not that my father read much biography anyway). It was Mozart’s compositions that moved my father and in which he found the stylistic and formal principles, and more especially the means of articulating ideas, that would influence the development of his own artistic language.

Most notably, Mozart (shameless imitator that he was) adhered to the maxim set forth by Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb in the mid-1940s: “The simple expression of the complex thought.” Ironically, the two artists made this declaration not at a time when they were painting the expansively scaled, pared-down abstractions for which they would become famous in the following decade, but during their Neo-Surrealist periods, when both were painting works of great complexity.

I have found time and again that my father’s writings on art prefigured the development of his work by several years; that he had generated and internalised the ideas before discovering how he could realise them in paint. The fact that Rothko and Gottlieb produced more readily Mozart-compliant works a decade after their manifesto does not change our understanding of the aesthetic and philosophical targets they were seeking.

Mark Rothko paintings hanging in the Tate in 2000.

Image courtesy of Ruthie V.

Rothko’s Yellow over Purple (1956). The artist’s colour-field paintings “are like a Mozart aria… making possible the most passionate communication”, his son says. Courtesy of Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko.

Image courtesy of The Art Newspaper.