Archive

Museums returning Benin Bronzes

There has been a lot of news recently about museums throughout the world returning Benin Bronzes to the Kingdom of Benin. This comes following years of speculation and outrage over a large number of looted artifacts that date back more than a century. Some attest the recent public outcry is partially because of last year’s exhibition “Art of Benin From Yesterday and Today: From Restitution to Revelation.” Coincidently, this important exhibition took place at the Kingdom’s presidential palace of Cotonou.

Now known as Benin City, Nigeria, Nigerians have called for these sacred artifacts to be returned to their rightful spot for decades. Courtesy of Ryan Waddoups for Surface Magazine, “Nigerians have called for the return of the stolen artifacts for decades, decrying their placement in Western museums as a potent reminder of colonialism’s ongoing reverberations throughout Africa.”

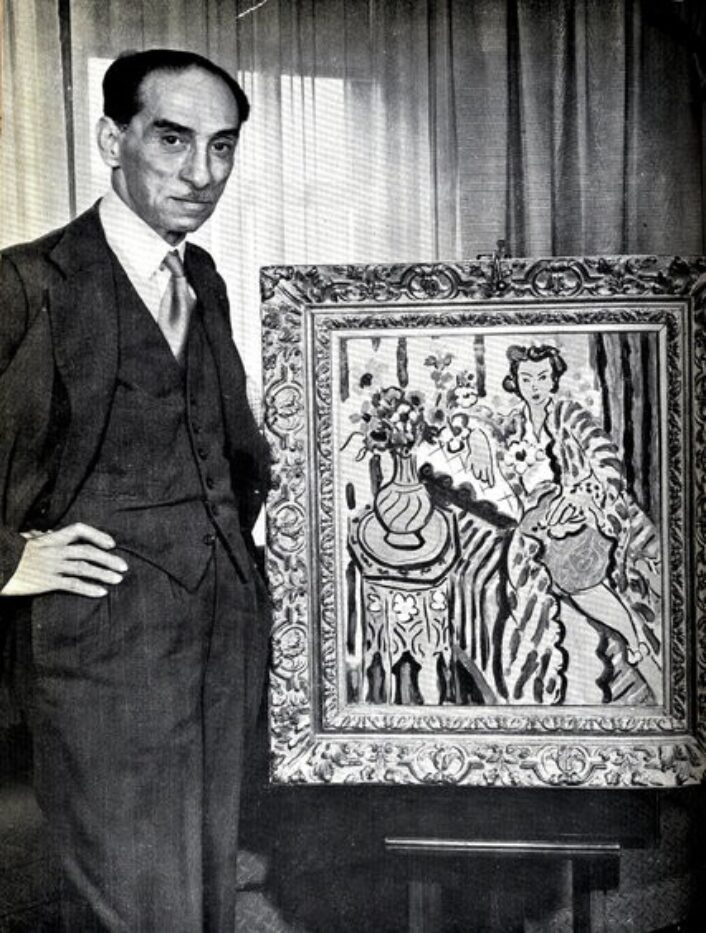

Circa the 1897 military exhibition to Benin City when British soldiers looted thousands of objects from the royal palace.

Image courtesy of: British Museum

Up to 10,000 bronze figurines, altars, ceremonial objects and plaques dating back to the mid-16th century were looted in 1897 when British soldiers invaded Edo in order to avenge the death of the explorer James Phillip. The Kingdom’s ruler, Oka Ovonramwen, resided in Edo, the “capital” of Benin, and graciously welcomed Phillip. However it was soon reported that Phillips and his expedition would disrupt a series of important rituals. Due to this, Phillip, his expedition members, and two-hundred African porters were murdered.

The British empire used this tragedy as an excuse to send troops to steal thousands of priceless objects from the Kingdom. Some items were presented on loan to the British Museums while others were sold to British and German museums, as well as to private dealers who went on to sell the artifacts to dealers.

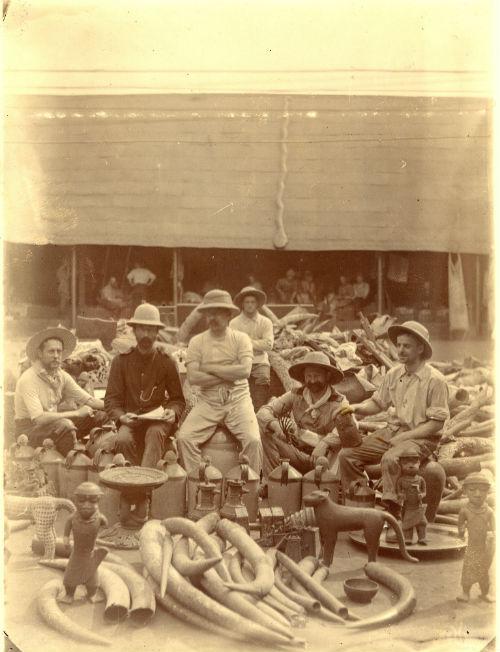

At the British Museum, cast brass plaques.

Image courtesy of: Art News, photographed by: Andreas Praefcke

It was only six years ago when the French president Emmanuel Macron publicly vowed to return the stolen artifacts to Benin. Macron stated “African heritage cannot be a prisoner of European museums.”

The British Museum, not surprisingly, possesses the largest number of Benin Bronzes in its collection. It has been stated that the Museum has more than 900 pieces in its holdings. In the unfortunate second place is Berlin’s Ethnological Museum (now part of the newly-built Humboldt Forum) which is said to own more than 500 objects from the Benin Bronzes grouping. Interestingly, Germany was the first to agree to retuning 1,100 disputed items to Nigeria.

Bracelet by and Edo artist, circa the 17th or 18th century.

Image courtesy of: Smithsonian Magazine

Next month the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Art’s (NMAfA) will return of 20 out of 29 items in possession. The remaining nine objects will remain on loan to the NMAfA for temporary display. Included in the works of art returning to Nigeria is a ceremonial sword made of copper, iron, alloy, and wood. In addition, a sculpture that depicts the head of a king with an emphasis on his beautifully-detailed beaded collar will return home.

Late last year, Digital Benin launched. The highly anticipated database of looted Benin Bronzes is a culmination of 5,246 artifacts being “held hostage” at 131 institutions across twenty countries. The data included comes from an exhaustive two year research project. The catalog that debuted provides information from the institutions themselves; specifically, the provenance of the artifacts and how they came to be a part of each institution’s collection.

A king and two attendants at MARKK Museum am Rothenbaum Kulturen und Künste der Wel.

Image courtesy of: Art Review

These efforts are important not just in regards to Benin Bronzes, but also due to a broader push by the art industry to fully understand an object’s provenance. The same applies to artwork acquired through colonialism or violence. This rings especially true with regards to artwork obtained via the Nazi regime.

Last year, the state of New York passed a law that requires all state museums to display if artwork was stolen by the Nazis. Jackie Mansky wrote for the Smithsonian (courtesy of Surface Magazine), “Uncovering the provenance of a piece can be slow work that sometimes never reaches resolution. That’s especially the case when art is swept up in war or politician instability.”