Culture

Nothing to waste, not even the bones

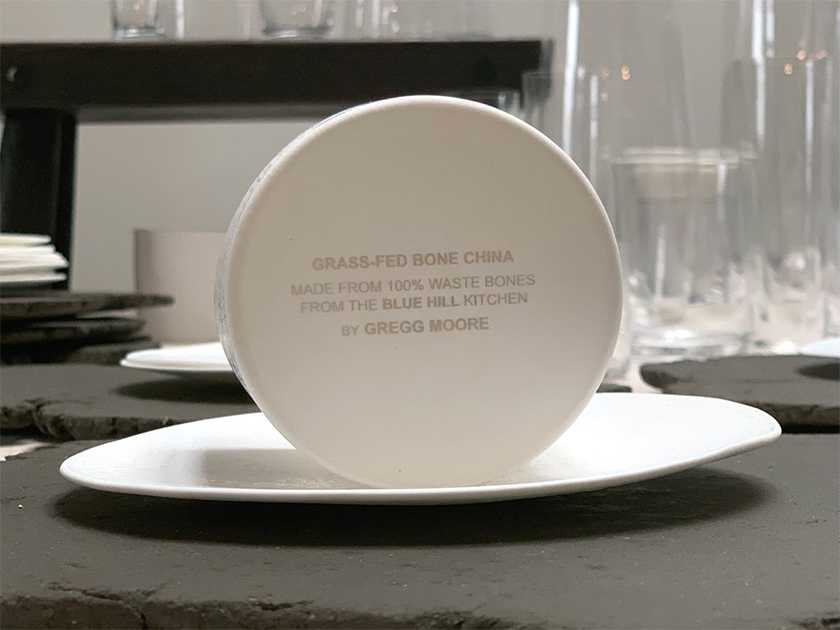

Gregg Moore’s china cups, which are made in his Pennsylvania studio.

Image courtesy of: Dezeen

In today’s world of sustainability and recycling, there is a huge exerted effort not to waste anything. However, Dan Barber, the chef from Blue Hill at Stone Barns, and ceramist Gregg Moore take that theory to another level completely.

Barber has received a plethora of accolades including multiple James Beard awards, the country’s Outstanding Chef award in 2009, and was appointed by President Barack Obama to serve on the President’s Council on Physical Fitness, Sports and Nutrition from 2008-2016. However, nothing excites him more than ensuring that absolutely nothing goes to waste!

The distinctive quality of the china is achieved using an 18th-century recipe for bone china, a type of porcelain made with animal bones.

Image courtesy of: Dezeen

So when ceramist Gregg Moore approached Barber and asked him why he hadn’t thought about being environmentally conscious with tablewares at his restaurant, Barber hit pause.

The chef and potter worked together to honor the farm’s whole-animal philosophy and made the restaurant’s china out of the farm’s cows’ bones. Barber raises the cows on pasture and, after they are slaughtered for meat, he gives the bones to Moore who transforms them into stunning tableware.

The pieces are so thin because they only spend a few seconds in the mold. Moore said, “I’m trying to get as thin a result as possible, and the less time the liquids spends in the mould the thinner the wall is.”

Image courtesy of; Dezeen

Moore created his version of bone china for Blue Hill at Stone Barns using the bones that went unused from the kitchen. The bones are cleaned and fired in a process called calcination (this turns them from a living material into calcium phosphate). Then, the bones get dried and pulverized to create bone ash and this goes into a mixture that is 50% bone ash, 25% English china stone, and 25% kaolin.

To achieve the purest possible result, the stone and the white kaolin clay is sourced from Cornwall England because the American equivalent is often “dirtier.” This mixture then gets folded into a liquid slip and cast into a mold where it remains for a mere three to five seconds.

Cow bones at various stages of processing.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Sarah Stolfa

The dishes dry for one day and then they are fired. They begin the process perfectly round and symmetrical; but the 2,400 degrees Fahrenheit heat causes them to warp. The forms that are the end result are gently curved and organic in shape.

Moore’s bone china recipe goes back to one formulated in 1799 by Josiah Spode, also known as the godfather of British porcelain. Around the mid-18th century, European ceramists attempted to replicate the smooth porcelain that came from China which was invented over a thousand years prior. It was the English artist, Thomas Frye, who first experimented with bone ash. Being the remnants after water, fat, and connective tissue are burned off, the recipe for bone china was tweaked by Spode and this is the one Moore uses today.

Underneath…

Image courtesy of: House Beautiful

Moore says, “What differentiates bone china from all other ceramic materials is that it’s made out of an element that was once living.” We couldn’t’ agree more!