Archive

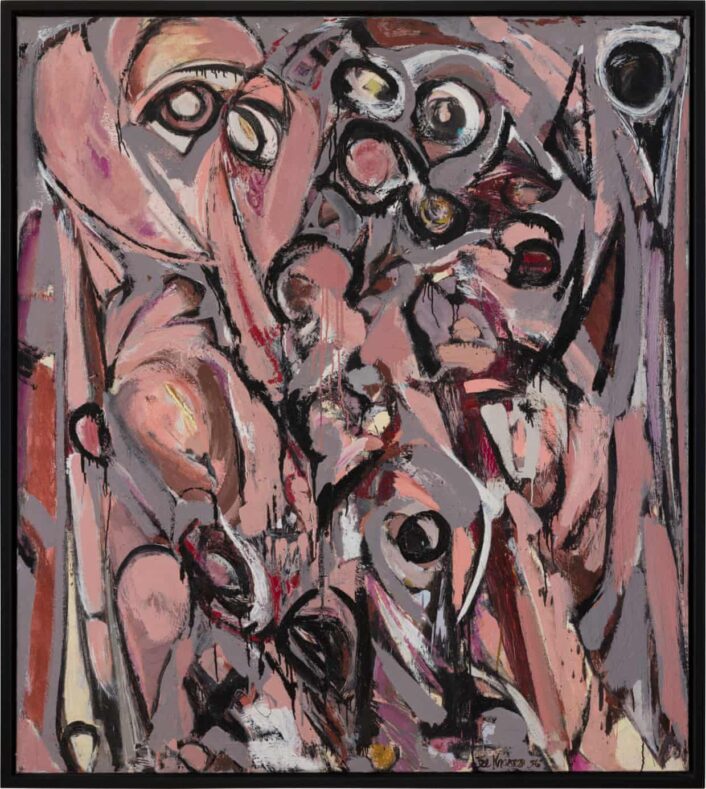

Philip Guston

“Pittore,” 1973. Titled after the Italian word for painter, “Pittore” portrays Guston as a crazed painter.

Image courtesy of: The Estate of Philip Guston/The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Promised Gift of Musa Guston Mayer (as featured in The New York Times)

Philip Guston is best known for his cartoonish paintings and drawings of subjects that range from uneventful daytime occurrences to political satires. Today, it is not uncommon to hear that claims stating that Guston helped shape 20th-century painting; however he remained an enigmatic figure throughout his career.

The Canadian-born artist was born to Jewish parents who had escaped persecution in Ukraine. At a young age, the family moved to Los Angeles where Guston’s interest in drawing and cartoons flourished. Guston befriended Jackson Pollock in high school; and in 1936, he followed Pollock to New York City. Guston wholeheartedly embraced abstraction after witnessing Pollock’s work. Together, the two artists became known for the most recognized abstract paintings from the 1950s.

“Mother and Child,” 1930. Oil on canvas.

Image courtesy of: Hauser & Wirth from The Estate of Philip Guston (as featured in Art News)

Throughout his career, Guston’s style was hard to pinpoint. A scholar of Italian Renaissance paintings, his work was inspired by the era… specifically by Piero della Francesca. As a young artist, Guston worked with some of the era’s most famous muralists and he personally made several murals in Los Angeles. Unfortunately, it was a 1932 mural of a Black man being whipped by a KKK member, as part of a larger series on racism in America, that brought him questionably, negative attention.

Over time, Guston switched from art style to art style. He dabbled in surrealism, inspired by Salvador Dali and his common subject matter of dreams and the unconscious. Finding success in abstraction, he delved into figuration. Pushing himself in new directions, Guston would often pick up subjects and styles he had previously experimented with. One thing is clear, he never created according to anyone else’s expectations.

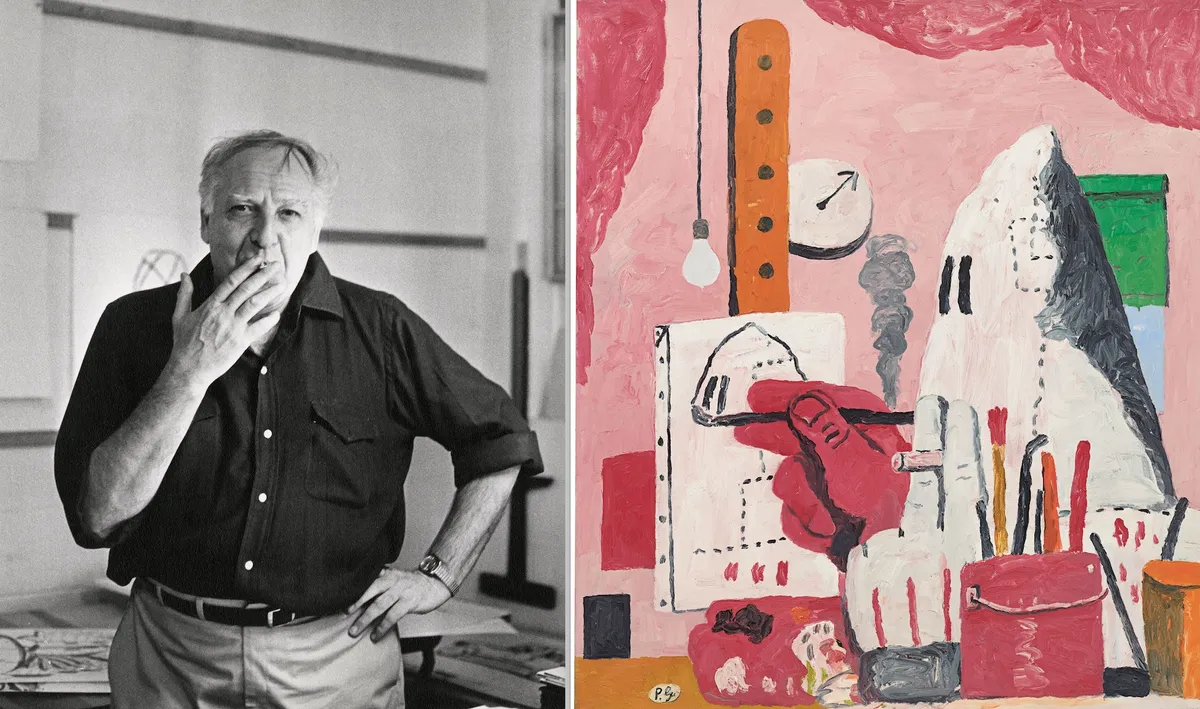

Guston (left) and “The Studio,” 1969 (right).

A common and recurring theme in his work, “self portraits” were Guston’s attempts to imagine himself being part of the Ku Klux Klan. Those thoughts presented questions such as: could he be evil, and what would it be like to plot against others.

Image courtesy of: The Estate of Philip Guston, photographed by: Frank R. Lloyd (as featured in The Art Newspaper)

Guston’s first major show was at Marlborough Gallery in New York City. In 1970, at the height of his career, the works he featured at the show (courtesy of National Gallery of Art) “are considered some of his most significant contributions to modern art.” Unfortunately, the works were misunderstood and he was crucified by critics. As an added strike against him, some artists were vocal about their resentment that Guston left behind the New York School style of abstract painting that he helped make famous.

Guston’s “new paintings” were large, horizontal canvases similar to billboards; the canvases were full of everyday objects painted in an oversimplified manner. A common figure that appeared in his work was in reference to the KKK; often, Guston would paint hooded figures in a time when the country’s political climate was charged and racism was rampant.

“Native’s Return,” 1957. Oil on canvas.

The painting is one of the artist’s strongest examples of abstract style; it was inspired by a trip to Italy where Guston became enamored with the clear compositions of Northern Italian painters.

Image courtesy of: The Phillips Collection

In 2020, “Philip Guston Now” was intended to open with a large-scale touring retrospective of the artist. However the politically charged time caused the four directors of the museums that were part of the tour to postpone the show that had been in the works for five years. A joint statement by the directors of National Gallery of Art in Washington, Tate Modern, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston and Boston, stated that the delay would continue until “a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.”

Even forty years earlier, when the paintings were first exhibited at Marlborough Gallery, the scathing reviews prompted to gallery to cease their contract with Guston. However for the artist, he felt as though he couldn’t quietly sit and watch what was happening in America. He said, “The war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue? I thought there must be some way I could do something about it.”

Installation view of “Philip Guston Now” from Washington’s National Gallery of Art

Image courtesy of: National Gallery of Art (as featured in The Brooklyn Rail)

The long-awaited “Philip Guston Now” retrospective opened at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in 2022. This summer, the tour’s final stop was at Washington’s National Gallery of Art. Interestingly, Trenton Doyle Hancock, an African American artist that focuses on KKK imagery said (courtesy of The Art Newspaper) “[Guston] made the case that the Klan was as American as apple pie. He didn’t run from this very American conversation in the 1960s and neither should we now.”

Regardless of the state of affairs, there is no doubt that Philip Guston was an instrumental part of art in the 20th century in America. His cartoonish figures hold much deeper meanings than initially suspected… but we mustn’t forget that those are the reasons we love art.