Architecture

Rotterdam’s yellow cube homes

Some of these homes are available to rent on Airbnb!

Image courtesy of: Rethinking The Future

One of Rotterdam’s most visited attractions is actually a grouping of yellow cube homes in Oude Haven, the historic section of the city’s populous port. Called Kubuswoningen, these homes were designed by Piet Blom, a Dutch architect who was known for his desire to challenge conventional design.

Both a popular tourist attraction and a strange architectural experiment, the cluster of 39 homes stands out amongst the city’s mostly modern architecture. However, that is what makes these “cube-perched-on-a-point” homes all the more interesting.

The Cube Houses were built in 1977.

Image courtesy of: Culture Tourist

World War II destroyed much of Rotterdam, as was the case with many European cities. The end of the war meant that there was a need and reason to rebuild the city in an architecturally-interesting way. Designing the city in a quick manner was very important; efforts were taken to ensure that the city’s design shy away from the utilitarian architecture that had previously existed.

Blom was asked to redevelop the area of Oude Haven with (courtesy of Arch Daily) “architecture of character.” This offered the architect the unique opportunity to apply his previous “cube housing exploration” in Helmand (a city in the southern part of the country). From the start, Blom knew that he did not want his project to resemble typical housing; he set out to challenge the idea that “a building has to be recognizable as a house for it to qualify as housing.”

Some other complications that preceded construction were the discovery of human remains which were imperative to leave undisturbed, contractor disagreements, ongoing problems with the district’s heading system that impacted the development’s buildable area, and an economic recession.

Image courtesy of: Rethinking The Future

Rotterdam’s urban planners set forth a few qualifications: the residential architecture needed to connect two small parts of land on each side of Blaak Street and the design needed to include a pedestrian bridge over the busy four-lane road. Since this was a busy traffic area, it was vital that the bridge connect the nearby market to the harbor. In addition, Blaak Street and the underground metro tunnel meant that there could not be any miscalculations in the foundation’s construction.

Even though 55 homes were in the original plan, only 38 were constructed. Two “super-cubes” were also erected; these larger units were not residential… rather, the southernmost super-cube was developed as a school of architecture and the northernmost super-cube was meant for commercial functions.

One Cube House is open to the public so that anyone who wants to experience what it feels like inside is able to do so.

Image courtesy of: The Boho Guide

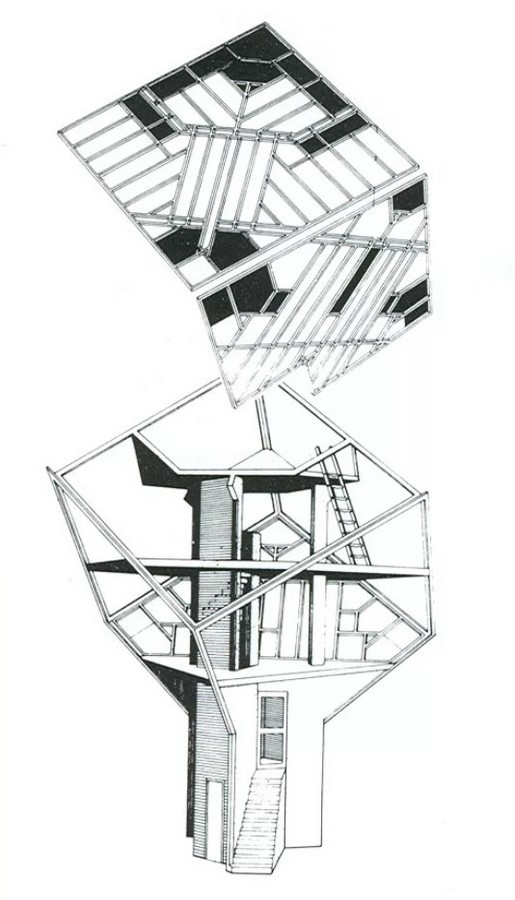

The elevated cubes are essentially houses supported on hexagonal piers; this design frees up the ground space for public use. Each cube measures 72 feet in height with each side measuring 25.5 feet. While the pillars and floor are made from reinforced concrete, structural wooden skeletons from the base for constructing the cubes were mounted on the floors’ edges. Interestingly, cement panels with rockwool insulation in the middle resulted in cutting down on almost all exterior sounds.

Inside, the complicated form meant that the interior walls were angled at 54.7 degrees with the floor. The consequences of this construction detail is that 25% of the almost 1,100-square-feet of living space is unusable because of the angular walls. The interior is divided into three floors that are connected by a narrow wooden staircase. The ground level houses in the living room and an open kitchen with plenty of windows. The second floor has two bedrooms, a bathroom, and a small living area. Finally, the third floor is a three-sided pyramid that can be used as a bedroom or an office.

In today’s Instagram-crazy age, a very popular photo op is to lie in the center of the complex and look up to see the roofs touching to form a star.

Image courtesy of: Culture Tourist

The Cube Homes were completed in 1984; since then, there have been a few changes. In 1998, zinc roofs were mounted over the original shingles for more insulation. The original retail spaces in the pedestrian “mall” were repurposed as studio spaces for small offices since some owners now work from home on a daily basis. In addition, the two super-cubes were converted into more functional spaces: one was turned into a youth hostel and the other is a transitional social housing facility.

Even all those years ago, Blom was spot on with his beliefs (courtesy of Arch Daily), “Architecture is more than creating a place to live. You create a society.” That is indeed what happened at Kuibuswoningen.