Culture

SFAI’s Diego Rivera Mural

“The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City”

Image courtesy of: Art Forum, photographed by: Jay Galvin

The past two and a half years have not been kind to art institutions. Unfortunately, the San Francisco Art Institute was no different in suffering an unfortunate fate. Struggling to stay open due to declining enrollment, expansion-related debt, and the temporary layoffs and closures due to the Covid-19 crisis, the school has struggled to cover the $19 million due in operating costs.

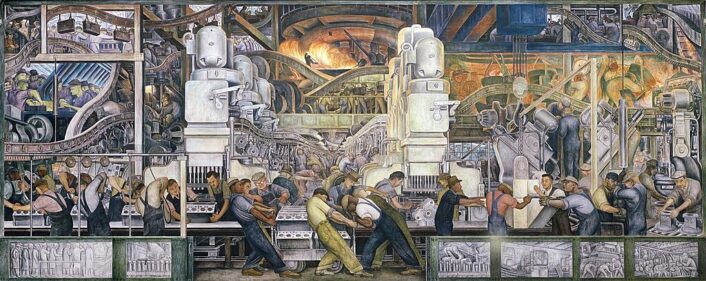

Perhaps SFAI’s most valuable asset was a 1931 mural by Diego Rivera titled “The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City.” The school’s president at the time commissioned the iconic work for $2,500. The site-specific mural depicts workers on scaffolding creating a fresco of a city in a stage of construction. For ninety years, the mural has served as an important piece in the history and culture of SFAI and the city.

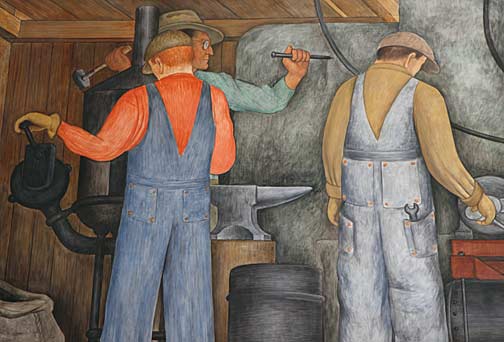

Rivera depicts the workers in detail which is aligned with his Marxist perspective that (courtesy of Art for a Change) “the workers produced all the wealth so they should be the masters of society.” Above, a worker operates a forge bellows, a sculptor hammers at an enormous stone block with a chisel, and a belt-machine operator works diligently.

Image courtesy of: Art for a Change, photographed by: Mark Vallen

The iconic mural depicts workings atop wooden scaffolding creating a fresco that presents a city in the midst of being built. For more than ninety years, the monumental 10-panel fresco has been omnipresent in the lobby of a theater at City College of San Francisco.

Completed in just one month, Rivera also painted himself working on the mural that has two levels: one level shows the building of a city while the other shows the creation of a fresco. Courtesy of Ronald Brichardson, “In the upper right section showing the steelworkers, the wood scaffold structure continues in the fresco-within-the fresco as steel girders, and, although the workers in the foreground are the same size as the figures on the wood scaffold, the scene depicted is clearly not within the gallery space. The three architect/engineer figures in the lower right panel are ambiguous—are they painted or working on site in a very confined space? Is the blue rectangle behind them an open window or a blueprint? Most likely it is a blueprint, since other rolled prints are leaned against the wall nearby.”

Since it was painted at an art school, Rivera believed it was important that the mural would showcase the actual process of creating the mural. Above, Rivera painted himself sitting next to his assistant who appears busy covering the wall with limestone plaster in preparation for the artist to paint.

Image courtesy of: Art for a Change, photographed by Mark Vallen

For many decades, the 10-panel fresco was tucked away in the lobby of a theater at City College of San Francisco. The monumental piece underwent a four-year, multi-million-dollar preservation project. Occurring in stages, the conservation work enlisted mechanical engineers, architects, fresco experts, riggers, art historians, and art handlers from both Mexico and the United States.

However when it became known that the SFAI considered selling the mural to help with the school’s expenditures, there was outrage. Sadly last summer, the 151-year-old institution closed permanently… this resulted in many questions; mainly, what will happen to the historic landmark mural painted by one of the world’s most recognized artists?

The mural is located on the Diego Rivera Gallery’s north wall, on the SFAI campus.

Image courtesy of: HyperAllergic

Last year, a $200,000 grant from the Mellon Foundation saved the mural from a public sale. In addition to directly impacting the mural, the funds will support public programming and scholarship as related to the mural. Also vital was to digitalize the plans… specifically the blueprints of the scaffolding used to create the mural.

SFAI board chair Lonnie Graham said, “The Diego Rivera mural occupies an essential and profoundly meaningful place in the culture and history of SFAI and San Francisco.” The additional funding will help the school to “elevate how we share the mural with the public by expanding cultural discourse and creating a broadly inclusive platform for social and academic collaboration.”

“Pan American Unity” was placed in a free gallery on the first floor of SFMOMA. Later this year, the mural will be carefully returned to City College.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Don Ross

The mural is one of three monumental pieces that Rivera produced for San Francisco. At City College of San Francisco, Rivera painted “Pan American Unity,” a mural that depicts workers from South, Central, and North America. Similar to other works, Rivera portrayed himself as a blue collar worker fighting for workers’ rights.

For many years, the 30-ton, 74-foot-wide-by-22-foot tall mural was essentially hidden from sight. Rivera himself foreshadowed a possible move… as evident by the fact that he painted on plaster with steel frames rather than directly on the wall. Hoping to get the mural more public interaction, a team spent years coming up with a plan on how to move the mural with the least amount of stress. Courtesy of The New York Times, “This spring, movers began the task of extricating the panels from the concrete wall. Threaded rods were slowly twisted into place above and below the mural by teams of movers situated inside and outside the building, who wore headsets to synchronize their actions as they simultaneously turned the rods — one-sixteenth of an inch at a time. It took two hours for one panel to move six inches.” The truck slated for the move was encased with custom-made shock absorbers; it drove at 5-miles-per-hour to ensure as little movement as possible for the precious cargo inside. After seven tedious trips, the mural was finally home at City College.