Fine Art

Simone Leigh’s ascension

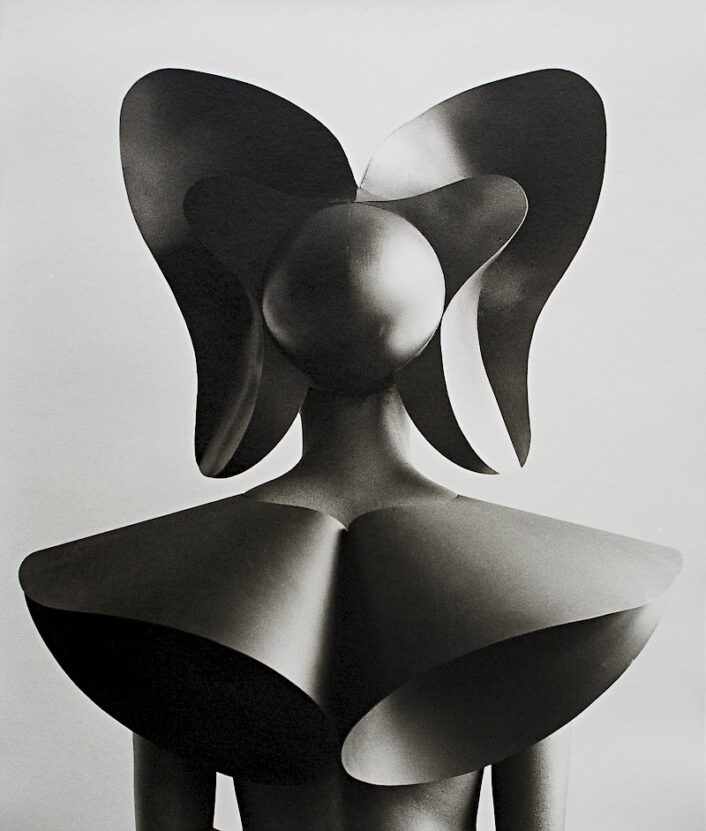

“Brick House,” bronze, 2019. Leigh was the first artist to be commissioned to present a piece for New York City’s High Line Plinth; this massive structure was unveiled in 2019.

Dimensions are: 196″ x 114″

Image courtesy of: Matthew Marks

When Simone Leigh was chosen to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, it marked the first time that a Black woman was selected to headline her country’s pavilion at the world’s top art festival. Courtesy of ArtNet, Jill Medvedow, Institute of Contemporary Art Boston’s director stated, “There’s no better artist for our time.”

The Brooklyn-based sculptor makes large-scale works that oftentimes address the social histories and personal experiences of Black women. For years, the single mom struggled within an art world that typically looked down on ceramics. Leigh’s “medium of choice” has long been considered (courtesy of The New Yorker), as a material for hobbyists or studio potters.” Luckily, Leigh’s unique style, far-reaching vision, and endless energy kept her going until a “breakthrough” that was so monumental that it led to the invitation to represent the United States at the world’s most prestigious and largest art fair.

“Hortense,” 2016. Made from terra cotta, India ink, glass beads, epoxy, porcelain, and 14-karat gold.

Dimensions are: 26″ x 16″ x 16″

Image courtesy of: The New Yorker

The Chicago-born artist is unapologetic in that her target audience has been and will always remain Black women. As she told the New York Times regarding the traditions of Black women, “have been left out of the archive or left out of history. I still think there is a lot to mine in terms of figuring out the survival tools these women have used to be so successful, despite being so compromised.” As protagonists, Leigh’s forms mimic distinctive figures… oftentimes faceless and staring into the abyss.

The past five years have been busy for Leigh… in 2018, she won the Hugo Boss Prize. In 2019, the sculptor took part in the Whitney Biennial and made the move from a major gallery, Hauser & Wirth, to the smaller Matthew Marks Gallery. The change came less than two years after Leigh joined Hauser & Wirth; it caused quite a sensation.

Simone and her crew at work. The impressive sculpture depicts a Black woman with braids. The torso was meant to look like a skirt-like house.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Michelle Gustafson

Initially, Leigh worked only with clay; however she is now quite proficient in bronze. These bronze sculpture are made by casting over clay models. The enormous pieces are made in a large room on the top floor of Stratton’s foundry. The three-story building with a rope-operated elevator is just perfect for Leigh… as it gives her the opportunity to work with Shane and Julia Stratton and their talented staff. This well-versed crew makes ceramic molds for each section of the sculpture, pour in the bronze, weld together the parts, and do the chasing and finishing.

As Shane and Julia like to point, they love being Leigh’s “backup singers;” and the twenty five years of experience owning their own foundry makes this a perfect combination. The 11,000-square-foot building in North East Philadelphia is a second home to Leigh. The small group of skilled craftsmen who work at the studio stay with a project from start to finish. This was just the “boutique-style” studio that Leigh was looking for. Luckily, the studio is able to assemble works up to 20 feet in height. An interesting fact, they melt up to four-hundred-fifty pounds of bronze per pour.

“Las Meninas,” 2019.

Image courtesy of: ArtNet, photographed by: Farzad Owrang

Leigh’s women are often missing features. Sometimes the figures have no ears, other times their eyes are smoothed over. The figures are holding tight onto secrets while seamlessly alluding to (courtesy of ArtNews), “centuries of undersold histories of Black resistance against colonialism, racism, sexism, and white supremacy.”

Traveling Africa since 2007, Leigh found a kinship with many African artists. What resonated the most with Leigh was that in South Africa, the artists used earth and common objects to construct, “They were working with material culture and not running away from it.” As such, Leigh’s 2016 outdoor project at Marcus Garvey Park let her African influences project outward. The project consisted of three hut-like structures built from clay with thatched roofs. These were inspired by rural Zimbabwe’s kitchen huts, or imbas. The traditional structures were used to hold meetings and hide valuables. However the huts were without an entrance which made it seem as though they were protecting a secret… a common theme. The imbas were curious enough; however what brought forth the magic was when Leigh placed a small ceramic head atop the center of the hut. She says, “That’s how those busts started that have house-like bodies.”

“Sentinel,” 2022. This 16-foot tall bronze sculpture was at the center of the rotunda inside the Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Gus Powell

Leigh was completely in charge in regards to her pavilion at the Venice Biennale. She hired the Italian-fluent Susan Thompson as the project manager and Pierpaolo Martiradonna, the architect who designed her Red Hook studio, as the Pavilion architect. Pierpaolo’s first step was to reinforce the floor so that it could support the bronze sculptures that would be made. Following, he designed the Pavilion to have a faux-classical thatched roof, per Leigh’s request.

Leigh titled her Bienelle show, “Sovereignty.” Perhaps that is because of the determination and perseverance it has taken for her to get to this place? Perhaps it was because of the magnitude Leigh headlining such a momentous affair signifies?