Fine Art

Sweden’s Af Klint

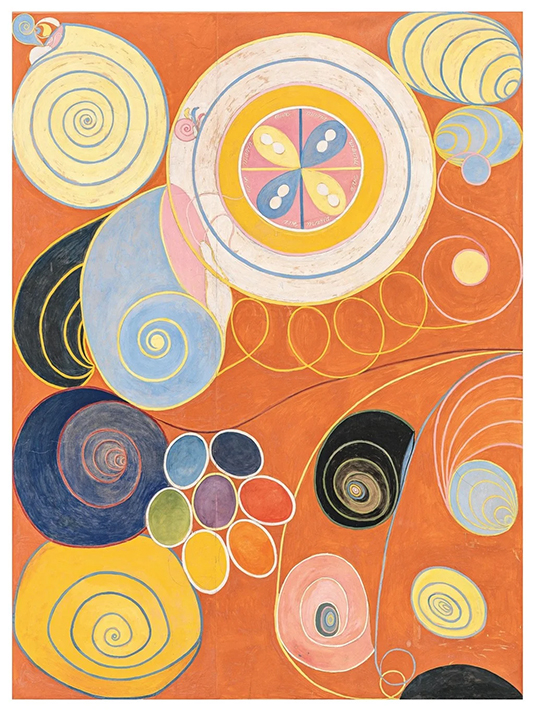

“Group IV, The Ten Largest, No. 3, Youth”, 1907.

Painting on loan from Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Image courtesy of: The New Yorker, photographed by: Albin Dahlstrom

Until the 1980’s, Hilma af Klint was virtually unknown to even the most proficient of art connoisseurs. The secretive Swedish artist created a huge assortment of bold, abstract, enormous compositions between 1906 and 1915. Some of the nearly 200 pieces were as large as 10 x 8 feet; and most were painted in a small, unknown studio in Stockholm’s center.

There is hardly a record of anyone viewing or discussing her work; and to maintain her anonymity, the artist destroyed nearly all correspondence a decade prior to her death in 1944. Last year, af Klint was the star of a six-month show at New York City’s Guggenheim Museum. Setting attendance records with 600,000 visitors, this much-awaited exhibition was her first solo show in America and on every art critic’s “to see for 2019” list.

“Group IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 17″, 1915.

Image courtesy of: The New Yorker, photographed by: Albin Dahlstrom

Af Klint is now being celebrated as a pioneering artist with a style similar to Wassily Kandinsky… although at least five years prior to “his time”. It was thought that the abstract style of artists like Kandisnky and Kazimir Malevich was revolutionary to them.

Part of this is because the artist left specific instructions stating that none of her work be shown until twenty years after her death. People have various thoughts as to why this was… the main thread relates to her spirituality. Graduating with honors from the Swedish Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1887, she was granted a studio with two other artists. By this time, af Kint had already embraced her spiritualism and was a regular attendee of seances since she was seventeen. Perhaps it was the death of one of her sisters that renewed her vigor?

Her personal life, however, centered around a group she formed with four other women named, “the Five.” At regular seances, they received messages from supernatural “High Masters” which they began documenting in simple, abstract drawings. From here on out, she channeled the visions she says she received from a spirit world. Who knows if such a things exists… but does it really matter?

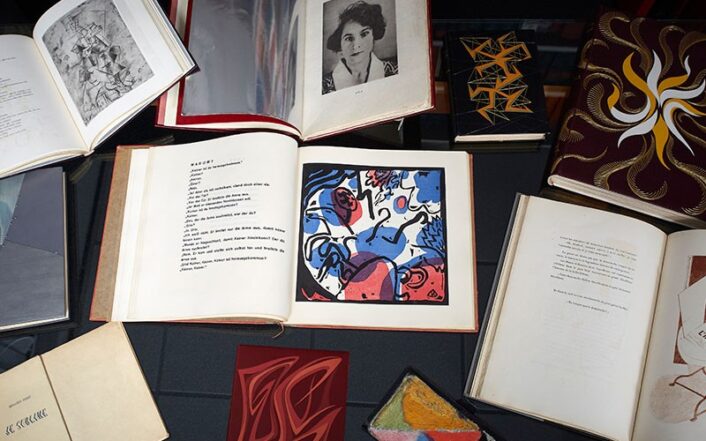

Hilma af Klint in her Hamngatan, Stockholm studio, circa 1895.

Image courtesy of: The Guardian

Af Klint’s paintings are abstract, lush, and flowing with variants of color which comes to us via looping floral and biomorphic forms. Sometimes there are letters, unique shapes, or indecipherable words that take their place on the canvas. It is all so innovative! What is clear is that very few people were privy to af Klint’s works during her life and perhaps it is because she felt that the world would only judge… not yet advanced enough to understand this non-descriptive style of art.

Thus the clause requesting that her work not be shown for at least twenty years after her death. When the crates were finally opened, it was her nephew, Erik af Klint, a naval man who had no knowledge in art, that was heir to these hibernating treasures. When the paintings were uncovered, 26,000 pages of accompanying notes detailing the creations were also unearthed. Much of the additional material pointed to a spiritual guide named Amaliel who came to af Klint during seances. The artist stated Amaliel didn’t “commission” the paintings, she actually directed her hand as she painted.

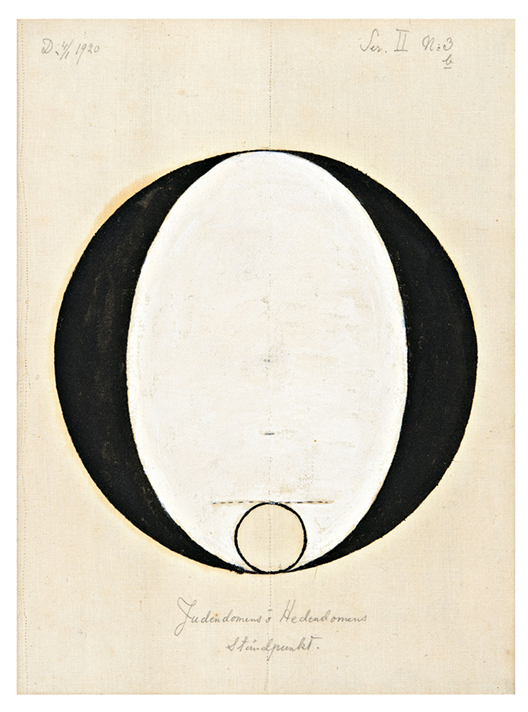

“Temple Series” speaks to an unknown cosmos.

Image courtesy of: CFHILL

Af Klint’s group, “The Five” was hardly alone in searching for existential answers and universal explanations about a higher power. The effects of the Industrial Revolution left society seeking connectedness. In addition, technological advances such as x-rays and atomic theory seemed to reinforce the possibility that there IS an existence beyond what is right in front of you. Af Klint was not the only artist who included abstract principles in her art, many other artists explored spirituality in their art during those days. Maybe it is because her work is relatively unfamiliar to audiences that we are seeing a freshness and newness to her paintings.

Whatever the reason, we couldn’t be happier that af Klint is having “her moment.”

“The Standpoints of Judaism and Heathendom, No. 3b”, 1920.

Image courtesy of: The Cut

Perhaps af Klint’s most recognizable collection was one of an “assignment” that she agreed to carry out at the age of 43. “Paintings for the Temple” was a commission which she was involved with between 1906 and 1915… this series would change her life.

Encompassing 193 paintings and subdivided into several series and sub-groups, these are some of the first pieces of abstract art that the Western world was presented. These predate, by several years, the first non-figurative compositions of af Klint’s contemporaries in Europe.

The choice to wait years to present her work was so that perhaps the world would find time to “catch up” with af Klint’s ideas. Even the famous Austrain philosopher, Rudolph Steiner, suggested to the artist, after seeing her work for the first time to wait fifty years before exhibiting. So she followed the suggestion… she agreed that the art belonged to the future and only in the future would they be properly understood by the public!