Fine Art

The influence of Mexican muralists

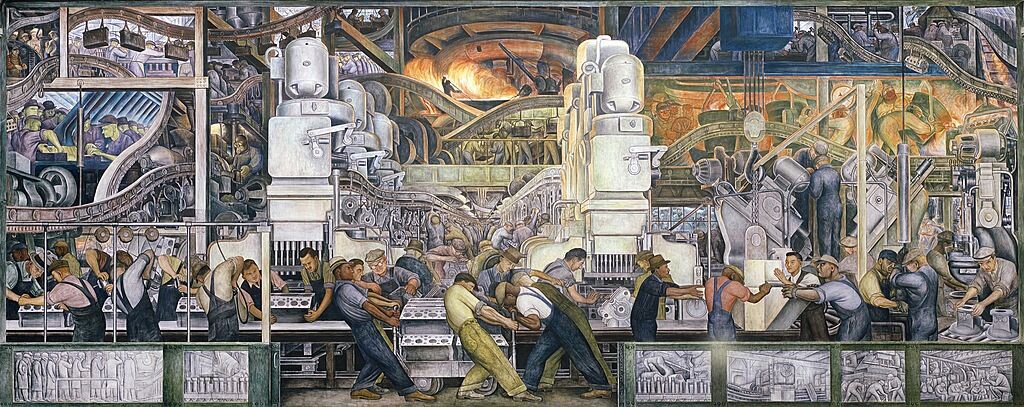

Lower panel of “Detroit Industry, North Wall”, 1923-33. Diego Rivera.

Rivera came to the United States in 1930 and was commissioned to create what would eventually become a 26-panel mural cycle filling all four walls of the covered courtyard of the Detroit Institute of Arts. This enormous undertaking began in 1932.

Image courtesy of: Whitney Museum of American Art

Some of America’s best known artists count European modernist artists such as Picasso and Miro as their biggest influences. However often overlooked is the time they spent in New York City’s Experimental Workshop. The studio was founded in 1936 by David Alfaro Siquerios, a Mexican social realist painter who is best known for his large murals in fresco. This political art workshop prepared floats ahead of the 1936 General Strike for Peace and the May Day parade. In addition, the Experimental Workshop produced a variety of posters for anti-fascist organizations in New York.

The large-scale works that they produced possessed the ability to reach “the masses” in ways different from mural paintings because they were easily accessible to a wide audience outside of museums and galleries. Herein lies the idea behind the post revolution Mexican muralist movement. Most influenced by this movement was Jackson Pollock, who worked attended the workshop and was heavily influenced by Siquerios, Diego Riera and Jose Clemente Ozozco.

In fact, Siquieros has been credited with teaching drip and pour techniques to Pollock that later resulted in his all-over paintings, made from 1947 to 1950, and which constitute Pollock’s greatest achievement. He was one of the most famous of the “Mexican muralists”

Mexico underwent a radical cultural transformation at the end of its Revolution in 1920. A new relationship between art and the public was established, giving rise to art that spoke directly to the people about social justice and national life. The model galvanized artists in the United States who were seeking to break free of European aesthetic domination to create publicly significant and accessible native art. Numerous American artists traveled to Mexico, and the leading Mexican muralists—José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros—spent extended periods of time in the United States, executing murals, paintings, and prints; exhibiting their work; and interacting with local artists. With approximately 200 works by sixty Mexican and American artists, this exhibition reorients art history by revealing the profound impact the Mexican muralists had on their counterparts in the United States during this period and the ways in which their example inspired American artists both to create epic narratives about American history and everyday life and to use their art to protest economic, social, and racial injustices.

Side-by-side comparisons that show the juxtaposition of Mexican and American art.

Left- “Christ Destroying His Cross, 1943. Jose Clemente Orozco.

Right- “Untitled (Naked Man With Knife)”, 1938-40. Jackson Pollock.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Emiliano Granado

The Whitney’s “Vida Americana” explores the profound impact of Mexican painters on America’s culture. This unique art form started in the 1920s after ten years of civil war and revolution. Mexico’s new constitutional government turned to art as a way of reinventing itself and broadcasting a unifying national self-image. This new campaign emphasized the deep roots Mexico had in indigenous pre-Hispanic culture and the heroism of its recent revolution struggles.

In Mexico, a new relationship between art and the public was evolving, giving rise to art that spoke to the population about social justice and national life. On the other side of the border, the model galvanized American artists who were seeking to break free from the aesthetics of European art. These artists were looking to provide the United States with accessible native art.

Left- “Reproduction of Prometheus”, 1930. Jose Clemente Orozco.

Right- “The Flame”, 1934-38. Jackson Pollock.

Image courtesy of: Time Magazine

The leading Mexican muralists, Jose Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siquerios all spent extended periods of time in the United States making murals, paintings, and prints as well as exhibiting their work and interacting with local artists. So admired were these three the they got a pseudonym, “Los Tres Grandes”,“the three great ones.”

The American artists that admired these muralists wanted to expose some of the social inequalities that were rampant under capitalism, all of which were exasperated by the Great Depression. Using the Mexican revolutionary experiment as a model, it seemed as though making art as a tool for social change was worth exploring.

The leadership change in Mexico lead to a less welcome feel for these self-identified Communists. Both mural commissions and far-left politics were on the rise; and in the United States, young artists were radicalized by the Depression and sought public art as a way of raising social consciousness.

Orozco arrived to New York in 1927 where he taught easel painting and printmaking to local artists. He moved to California and in 1930, Orozco executed a mural commission for Pomona College called “Prometheus.” A teenager living in Los Angeles at the time, Pollock says that seeing “Prometheus” was something he would never forget.

“Self Portrait”, 1945. David Alfaro Siqueiros.

From the very start of his career, Siquerios made it publicly known that he would not take any commission or artistic assignment that would compromise his personal ideology.

Image courtesy of: WideWalls

Siquerios was the most revolutionary of the three; as such, he took the most radical formal chances in his art. In 1932, he painted “Tropical America: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos” (“Tropical America: Opressed and Destroyed by Imperialism.” Those who commissioned the painting were offended by Siquerios’ take on “Yankee” aggression and whited out the painting.

Siquerios influenced many young artists who assisted and emulated him. Among those were artists of a diverse ethnicity. Eitaro Ishigaki, a Japanese-American painter was marginalized by his immigrant status and racial identity; the same was true for many Latino and black artists of the time.

If national unity was the idea, the debut of Charles White’s “Five Great American Negroes” public mural was a perfect example of the epic nature of the works created during this time. White’s mural includes portraits of Sojourner Truth, Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver, Marian Anderson, and Frederick Douglas. Credited with helping to create a new national identity for America, White wanted to ensure that the history of African Americans was also included.

Taking cues from Mexico, which was able to create epic works with the mission of unifying their war-torn country, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt realized the need for a similar movement in the United States. In the midst of the Great Depression, Roosevelt established the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project in 1935. The aim was revolutionary, making art a part of public life.

As much as “Los Tres Grandes” never neglected to shy away from depicting the injustices of their era, their American counterparts were equally set on creating a new and inclusive national identity for their healing country. The influences of the premier Mexican muralists remains strong!