Design

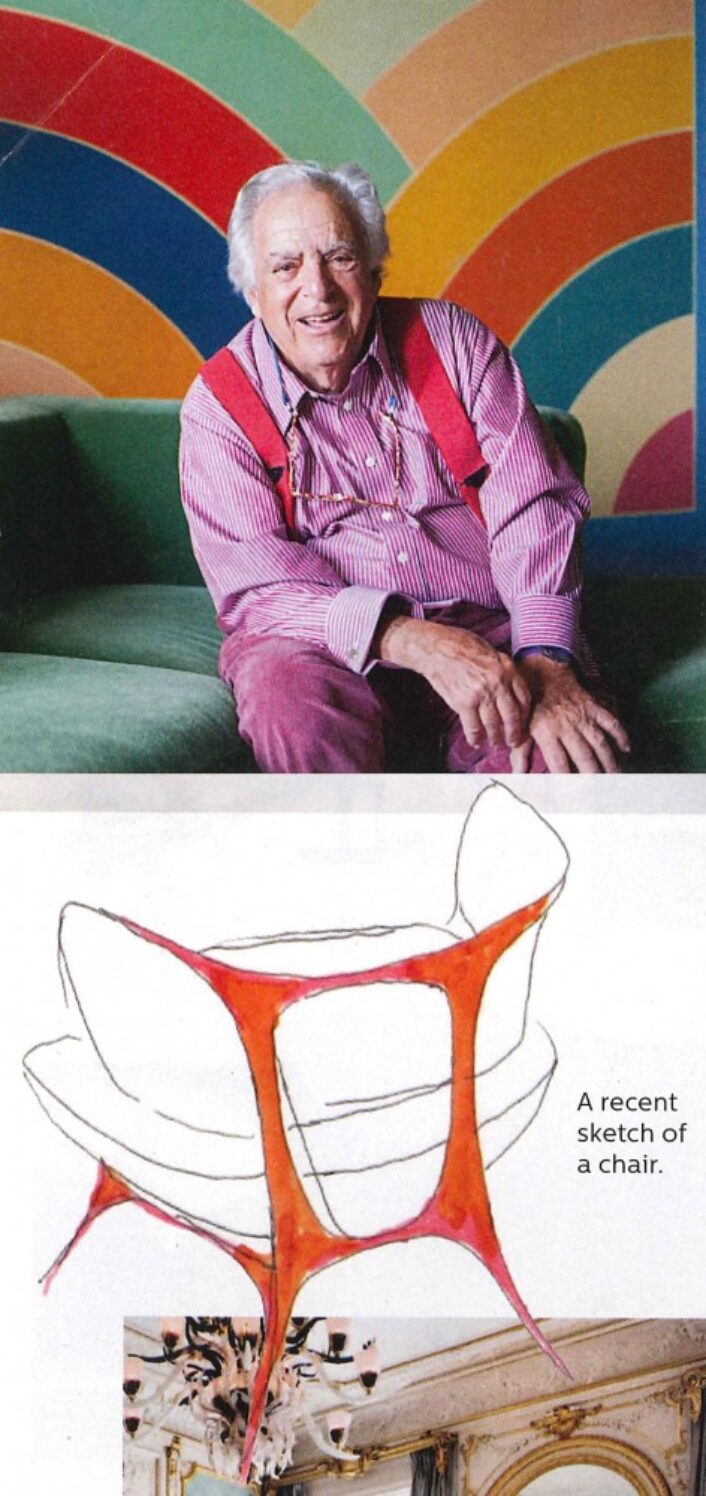

Vladimir Kagan proves timeless

A showcase of Vladimir Kagan pieces.

Image courtesy of: Vladimir Kagan

Vladimir Kagan is considered an icon of mid-century furniture design; he is often mentioned alongside contemporaries such as George Nelson, Eero Saarinen, and Edward Wormley. Kagan however, differs from most of his peers in that he remained a New Yorker through and through while most of his peers moved to the West Coast to showcase their designs. Others still joined American companies such as Knoll, Herman Miller, and Dunbar where the mass-produced pieces were furnishing homes and offices across the country. Kagan stayed true to himself for the duration of his long career.

Kagan remained linked to his city throughout the span of his life. His upbringing as a first generation child of immigrants who fled Europe and landed in New York inspired much of his work. In particular, Kagan’s early works are closely tied to his experiences growing up in New York City.

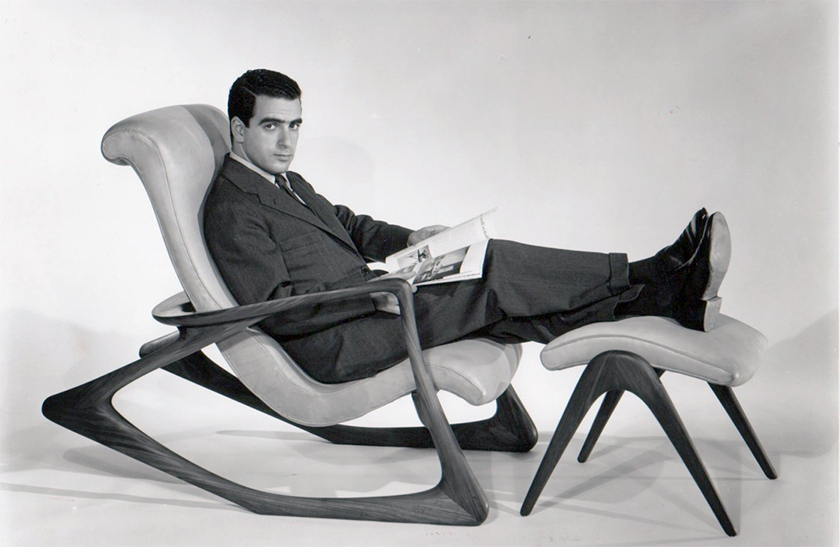

Kagan sitting in his ‘Two Position’ Contour Rocker, circa 1955.

Image courtesy of: MCM Daily

It is no surprise that furniture making was in Kagan’s blood. When his family survived a dramatic escape from the Nazis and made a home in the United States, they brought with them the legacy of furniture making. In the Old World, Kagan’s maternal grandfather had previously owned a shop that specialized in (courtesy of Phillips), “peasant art, furnishings, and costumes into the staid old Munich society.” The youngster’s aspirations differed however as he veered towards sculpting.

The combination of traditional crafts with a nod toward modernism and abstraction would coincide years later when father and son worked together in Manhattan. The two opposites worked at their factory on East End Avenue where Kagan successfully reworked his father’s abstract, out-of-proportion sculptures into functional pieces such as table bases and chair frames. He explained, “I wanted to create a piece of sculpture and saw no reason why a chair could not have the same derivative spark.”

In the formal living room of our Scarsdale Residence, we used Kagan’s Serpentine Sofa as a graceful anchor in this seating area. The sofa was purchased from Pucci, and upholstered in fabric by Le Manach through Pierre Frey.

Photographed by Eric Piasecki

View more of this residence

Kagan was drawn to minimalist design which was spurred by his desire to be an architect, and by the Bauhaus movement which was familiar to him because of his father. However, he was also inspired by Scandinavian designs’ purity at the time his peers were creating sleek, industrial pieces.

A lifelong learner, Kagan studied anatomy in order to fully understand how to properly brace a spine and provide the adequate lumbar support. Especially, Kagan was drawn to the female torso as evident by the “sinuous and sensual lines and details” found in many of his curvaceous sofas. In 1950, Kagan opened the Kagan-Dreyfuss on East 57th Street. The desiger was immediately popular amongst the wealthy patrons who wanted to transform their homes by purchasing avant-garde pieces.

Eitel sitting on the “Barrel” sofa at the furniture workshop.

The young designer joined Kagan’s studio in 2013; he was instrumental in helping to create some of Kagan’s limited-edition pieces for showrooms such as Ralph Pucci and Carpenters Workshop Gallery.

Image courtesy of: Wallpaper, photographed by: Steve Benisty

Last year, Vladimir Kagan Design Group collaborated with Holly Hunt to present ten pieces created by the designer between the 1940’s and 1980’s. The group joined Holly Hunt in 2016; however until recently, the two separate entities had not produced a collection together. Curated by Chris Eitel, the idea was to explore the key themes in Kagan’s work. Eitel, a former Kagan protege and director of design and production at Vladimir Kagan Design Group, hope to preserve (courtesy of Wallpaper) “the designer’s legacy with minimal functional or material adjustments.” Mainly, the pieces reissued reflect the two themes commonly found in Kagan’s work, “linear architecture and organic forms.”

Eitel adds, “We wanted to just explore his career a little bit and pull from decades, see what his influences were from the 1940’s through the 1980’s, find some pieces that people might not have had access to for a long time, and pick things that we were attracted to, and that we thought we could bring forward in a contemporary and modern way.”

Erica low-back lounge chair; the piece debuted at Miami Art Week in late 2021.

Inmage courtesy of: Galerie Magazine, photographed by: Josh Gaddy

When Holly Hunt acquired Vladimir Kagan Design Studio, the plan was to continue supporting its work. Jo Anna Kornak, senior vice-president and executive creative director at Holly Hunt said, “Vladimir Kagan’s work embodies a lifelong dedication to the handcrafted and exquisite. [We are] honoured to continue that legacy, and work with Chris and the Vladimir Kagan Design Studio to create heirloom pieces that respond to the changing modern world.”

The 10-piece collection was masterfully updated with contemporary materials and manufacturing methods that include new fabrics, foams, and little pieces of hardware. To best translate Kagan’s intent, hand-drawn details were digitalized and vintage designs were deconstructed. Eitel who lead the change said (courtesy of Galerie Magazine), “It’s a process of styling and deciphering.”