Culture

Who knew there was a museum in the Korean DMZ?

Haegue Yang’s “Migratory DMZ Birds on Asymmetric Lens — Kyott Kyott Vessel (Pale Thrush),” 2021. From the museum’s inaugural exhibition.

To reach this five-foot-tall block of grey soapstone with a translucent bird perched atop, Yang needed a bulletproof vest. The deceptive work can appear either circular of spherical; the bird is made from 3D-printed in resin and it is separated from the center (as visible from certain perspectives).

Image courtesy of: ArtNet, photographed by: Shinwook Kim

Late last year, a museum opened in the Korean Demilitarized Zone. The hope was that this new endeavor would eventually, in a small way, help to promote goodwill between North and South Korea. Called the UniMARU Art Museum, the inaugural exhibition took place in September 2021 and it was titled, “2021 DMZ Art and Peace Platform.”

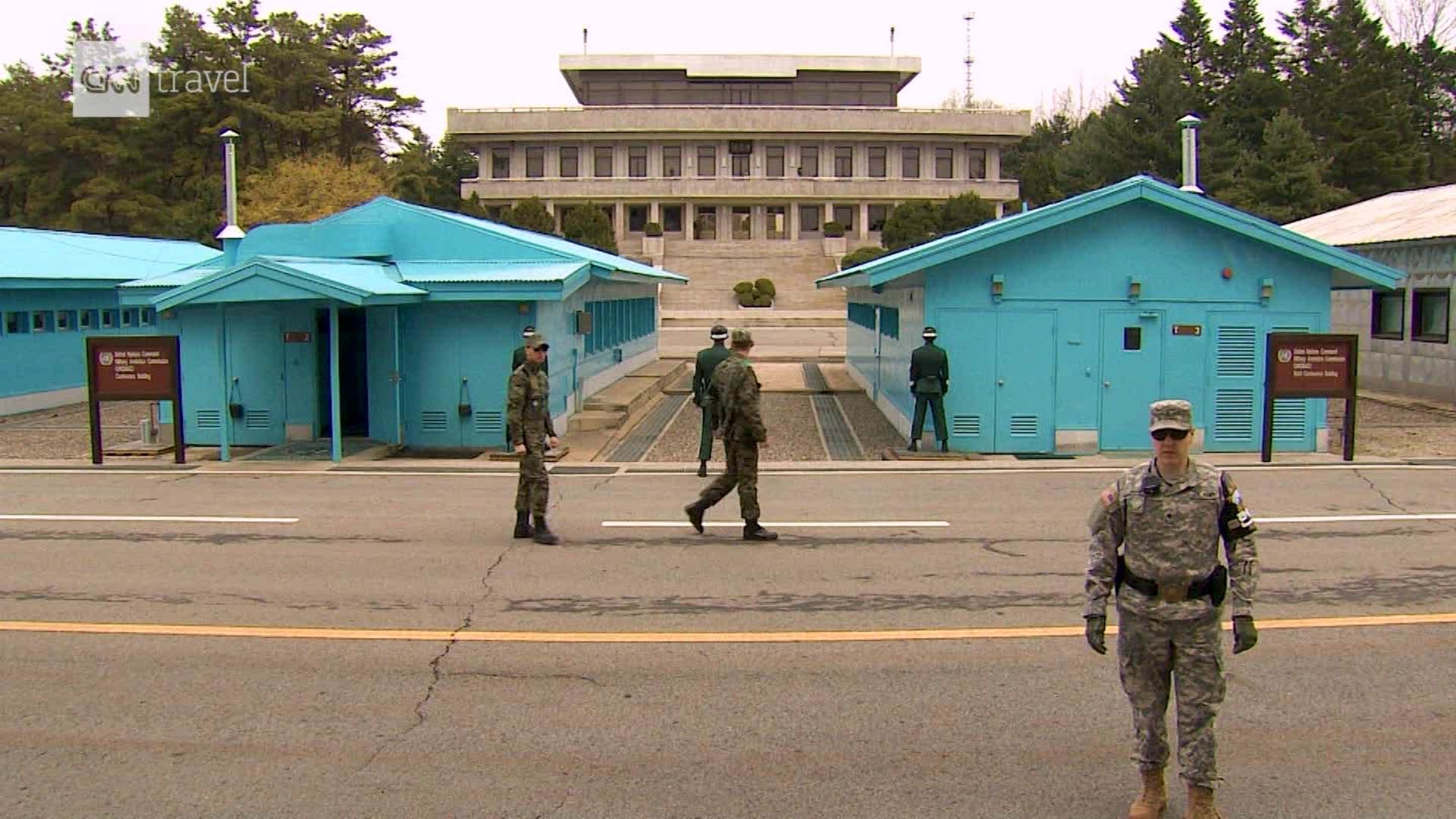

The DMZ is a thin strip of land that divides the Korean peninsula on either sides of the 28th parallel, at the border between North Korea and South Korea. The location is one of the most heavily militarized regions in the world and access is granted only via the North Korean government or the United Nations Command.

Nam June Park, “Elephant Cart, 2001” This piece is part of UniMARU’s first show, “2021 DMZ Art and Peace Platform.”

Image courtesy of: ArtNet, photographed by: Kim San

The building itself has a long and interesting history. UniMARU was built in 2003 as a temporary inter-Korean customs office that screened visitors prior to their entrance to the DMZ. However with the region’s escalating tensions, the office opened a larger location in 2007; this left the former space vacant.

The gut rehab from architect Hyunjun Mihn and the firm MPART transformed the former governmental structure into a high-ceiling venue for contemporary art. Luckily, Mihn had previous experience with museums; he was in charge of designing Seoul’s Museum of Modern Contemporary Art. The museum’s name is important; a portmanteau of the two works “uni” for unification and “maru,” the Korean word for space or platform. In essence, the name itself demonstrates the hope that this place will become a platform for peace.

Left- Sulki and Min’s “here/Here,” 2021. Single-channel video projection.

Right- Sungmi Lee’s “Invisible and Visible,” 2021.

Image courtesy of: Museum Next

The museum’s artist director, Yeon Shim Chung, hopes that artists from North Korea will eventually be allowed to participate in exhibitions. This is the reasoning behind the blank spaces and empty frames adjacent to exhibited works… they are, in essence, in a waiting pattern. The first exhibition showcased the works of 32 Korean and international artists whose subject matter reflects on war, displacement, borders, and other current issues from peace including climate change. The show was hosted by the Inter-Korean Immigration Office of the Ministry of Unification with the support of the Inter-Korean Transit Office.

Chung told Museum Next, “This exhibition attempts to construct peace and ecology zones in order to re-envision Korea’s DMZ, which is currently a symbol of division and war. It also seeks to establish art communities in the DMZ to commemorate the painful memories of the past.”

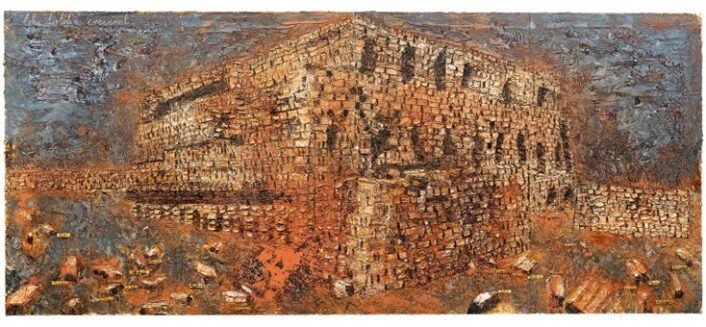

From a different perspective…

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Shinwook Kim.

Part of the exhibition was on view at separate locations- two DMZ train stations: one nearby, Dorsal Station, and one on the peninsula’s east coast, Jejin Station. Both terminals remain active in the event that the countries open their borders and mass transportation between the two nations is needed.

Perhaps the most emotional exhibition location is on the site of a former guard post, roughly one mile from the border. At this site, the Korean Artist Hague Yang was asked to present her “Migratory DMZ Birds on Asymmetric Lens- Kyott Kyott Vessel (Pale Thrush).” Chung commissioned this piece after falling in love with Yang’s “Ground/work” from the 2020 Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Military presence at the DMZ faces the museum.

Image courtesy of: CNN

Surely, this is the only museum where visitors must don bulletproof vests in order to get close to the artwork. Security concerns mean that the number of daily visitors remains quite small. A maximum of five groups are allowed each day, and no group can be larger than thirty. Those who want to visit UniMARU must apply for permission at the South Korea Ministry of Unification. Once permission is granted, they receive a free ticket to the museum and can board one of the buses that takes guests to the DMZ.

Once identification is checked, visitors are escorted around the museum. A strict dress code ensures that guests do not wear shorts, miniskirts, or anything with a fatigue print. Waving and taking pictures without permission is forbidden and no children under eight years old are allowed.