Architecture

Wilshire Boulevard Temple expansion

The Whilshire Boulvard Temple and the Audrey Irmas Pavilion.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Jason O’Rear

An expansion to Beverly Hill’s Wilshire Boulevard Temple was a tough proposition. Home to the oldest Jewish congregation in Los Angeles, the temple was designed by Abram M. Edelman and built in 1929. As a mixture of Byzantine and Romanesque styles, the famous domed synagogue is fitting for the city that is home to glamour and entertainment.

In 2015, the congregation launched an international design competition for a new structure which would encompass the Karsh Family Social Service Center, school buildings, and recreational areas. The new facility would serve, “first and foremost, as a place of gathering.”

Looking up, it’s 130 feet to the dome’s apex.

Image courtesy of: Cleveland Jewish News

The Temple is a nod to Rome’s Pantheon; topped with a large Byzantine revival dome, it is listed on the National Register of Historical Places. Also serving as one of Los Angeles’ Historic Cultural Monuments, the Moorish-style building was finished in 1929. Adding to the storied history, the architect was the son of the congregation’s first rabbi, Abram Wolf Edelman.

The institution’s history began when the first noted worship services were held in 1851. The following year, the small number of the city’s Jewish people received their charger from the state to found Congregation B’nai B’rith. In an attempt to keep up with San Francisco’s more prominent Jewish community, the decision was made to commission the congregation’s first building. In 1896, the congregation moved to a larger building; however it was not until the current Wilshire Boulevard Temple opened in 1929 that the community felt a sense of pride in their Jewish identity. Along with some of the city’s pioneers and Hollywood moguls, the new synagogue was the dream of Rabbi Edgar Magnin. Known as the “Rabbi to the stars,” Rabbi Magnin was responsible for attracting the city’s elite to his “modern vision of Judaism.”

Inside, the new temple includes a number of murals commissioned by the Warner Brothers. The enormous murals are 320-feet-long and 7-feet-tall; they illustrate important moments in Jewish history. Most impressive is the Temple’s dome with imposing marble columns that represented Hollywood magic. Different than many synagogues, there is no central aisle; the idea is so that it feels like an open movie theater.

The 55,000 square foot pavilion.

Image courtesy of: Audrey Irmas Pavilion

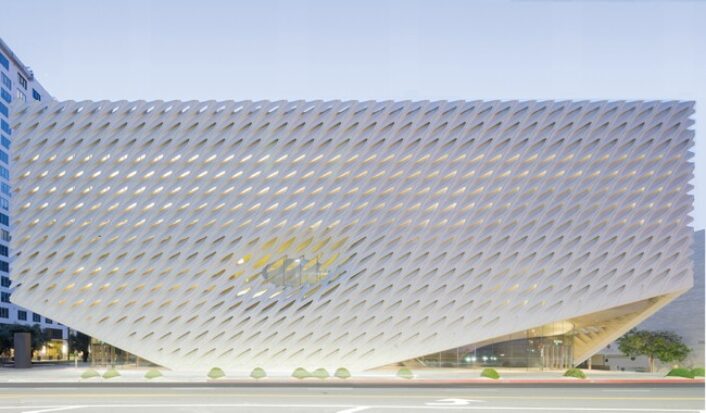

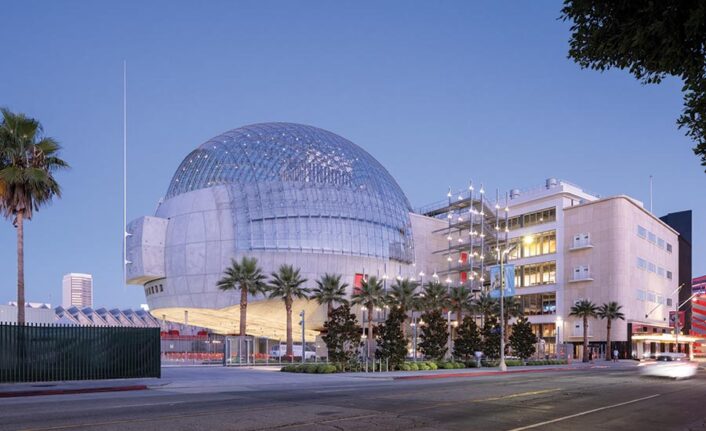

OMA, a Rotterdam-based architecture firm won the prestigious commission. It is the firm’s first commission for a religious institution and its first cultural building in California although it came in second in the design competition for the Los Angeles’ Broad Museum and the renovation of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Partner Shohei Shigematsu, head of OMA’s New York City office, lead the ambitious project. Named the Audrey Irmas Pavilion in honor of the top donor who funded $30 million toward the new structure, the 2015 donation launched the capital campaign. The gift was among the largest donation to a temple in the United States. Irmas describes her intentions (courtesy of the Audrey Irmas Pavilion site), “As a life-long member of the congregation and the lead donor supporting the Audrey Irmas Pavilion, I am elated to see the building come to completion even more spectacularly than it was originally envisioned. This building will be an important gathering space enjoyed by the wider community for years to come, and I am overjoyed to be a part of its beginnings.”

Steve Leder, the temple’s senior rabbi, pointed to the fact that the Covid pandemic caused a lot of pent-up demand for people to connect… to just be together. The building’s opening occurred at the perfect time.

Image courtesy of: ArchPaper, photographed by: Jason O’Rear

The addition’s facade is clad in 1,230 hexagonal panels that “house” rectangular windows. Inside, the three connected event spaces fill the voids. The grand ballroom on the first floor is a column-free, expansive space with vaulted ceilings made from a sassandra wood veneer that feeds off the polished red concrete with exposed aggregate flooring. The second floor contains a trapezoidal chapel and an outdoor terrace that frames views of the temple’s stained-glass windows. Traditional in style, the windows mimic churches with compositions of Renaissance paintings. The third floor is a completely non-denominational space; it houses the Wallis Annenberg GenSpace, a community center for older adults. Founded by its namesake, Annenberg is one of Los Angeles’ most recognized philanthropists. The center is beautifully laid out around a circular sunken garden that leads to a rooftop terrace.

Intentional, the new structure leans away from the temple “in a show of reverence for the historic structures.” In addition to the philosophical meaning, this also opens up the existing courtyard to a plethora of natural light. As event spaces are typically used for a wide variety of purposes, it was pertinent that there was flexibility within the structure’s design. Shigematsu says that this was one of the project’s main challenges.

On the first floor, the main event space has beautiful arches and is acoustically treated with sassandra veneer.

Image courtesy of: World Architects, photographed by: Jason O’Rear

There is no direct entrance from Los Angeles’ major boulevards; rather, an imposing steel fence greets pedestrians. Sadly, recent anti-Semitic violence made it necessary to institute basic security protocols which slightly disturbed the structure’s openness.

Having no blatant “front door” was a problem when the time came for placing the mezuzot (the Jewish custom of placing a small piece of parchment printed with a Bible verse that reminds people of their commitment to God). Rem Koolhaas and Shigematsu ensured that there IS an actual front door that has a 27-foot-tall arched window which is said to mimic the synagogue’s copper dome.

Shigamatsu told Dezeen upon the finishing the commission, “Its completion comes at a time when we hope to come together again, and this building can be a platform to reinstate the importance of gathering, exchange, and communal spirit.”