Culture

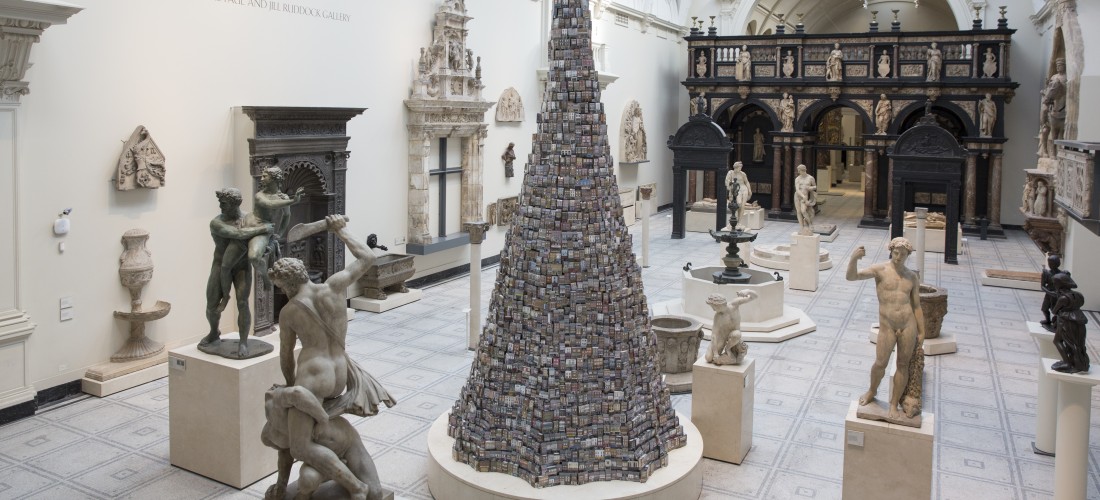

A tower full of London’s shops

In order to create this impressive and huge masterpiece, Barnaby cycled over 1,000 miles and photographed roughly 3,000 shops. The storefront he recreated ran the gamut from Vietnamese nail salons to French designer boutiques. As with a typical pyramid scheme, the more derelict storefronts are at the base and as you scan upward, you see mini versions of auction houses and prestigious art boutiques! Image courtesy of: London Design Festival

British artist, Barnaby Barford is probably best known for his “Tower of Babel” installation which debuted in 2015. While displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum, the 21-foot tall structure was made up of 3,000 individual bone china buildings. Each edifice is a copy of a real-life London shop that Barford photographed while on his 9 month mission of reconnaissance by bike through every section of London.

The company, True Staging, worked with Barnaby Barford to create the “infrastructure” which housed these individual buildings. A wooden building was made as the tower’s core, it was then covered with mesh and sprayed with foam which was carved into the necessary shape. Image courtesy of: True Staging

While on display, some 2,500 individual “houses” were sold. Now, more pieces are being sold… the price dependent upon the piece’s placement on the pyramid. The finished product showcases the wide economic divide within the city. London is often known and treasured as welcoming people from all over the world, a place where hundreds of languages are spoken, and where immigrants can open a store and begin their own “tower of commerce”.

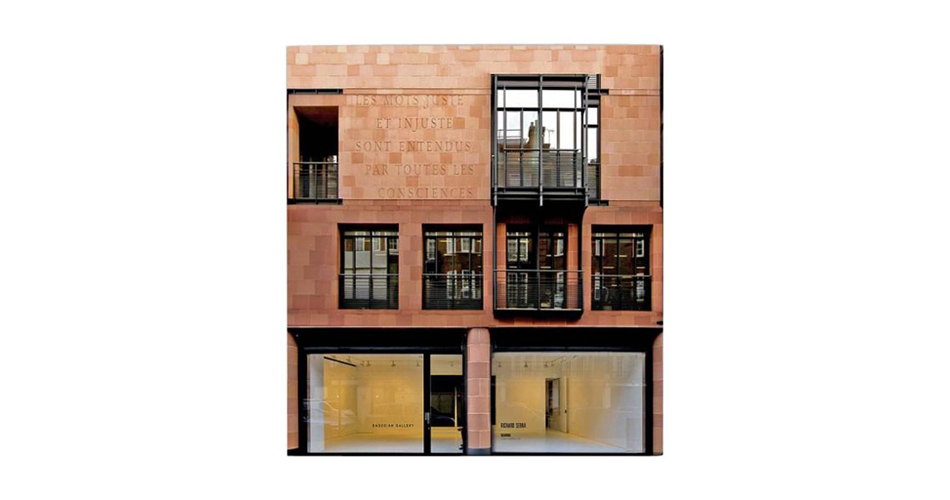

Barnaby Barford, Tower of Babel: Sculpture Number 0003, 17-19 Davies Street (W1K3DE), 2015. On Davies Street, this building is a well-known contemporary-art gallery. Here, it’s portrayed with Richard Serra’s drawings exhibition. The quote on the facade, “Les mots juste et injuste sont entendus par toutes les consciences” from Louis Antoine Léon de Saint-Just (1764–1794), a French politician and revolutionary. It’s interesting that these words ended up on a brand new building’s facade! Image courtesy of: 1st dibs

Barford meant this as a celebration to the city, not necessarily as a critique of London’s divide between the rich and the poor. The city has a very rich history of trade and commerce which independent traders enhanced over the years. Barford said he was most satisfied by the fact that people would come and spend hours circling the tower, looking for buildings that they recognized. Visitors came looking for their shops among the 3,000 pieces; and once found, they were overjoyed.

When the suggestion to sell the individual pieces are sounded, initially, Barford strongly discouraged it. After further thought, the artist realized that since the piece was really about consumerism, it would make perfect sense to sell the buildings.

Here, Barnaby is showing adhering the individual storefronts onto the tower. The “Tower of Babel” was created for the Victoria and Albert Museum. Image courtesy of: Platform

Studying at the Royal College of Art, Barnaby was always curious about ceramics. Early on, the artist says he liked using both antique and mass-produced porcelain figurines. After amassing a collection, he chopped them up and painted them… thereby producing a contemporary scene. The repetition of hundreds of objects coming together to make something unique is what drew Barford to ceramics.

Image courtesy of: The Tower of Babel

There are social issues pointedly displayed within the “Tower of Babel” that Barnaby subtly explores. Presenting a favorite pastime of locals… shopping, the Tower forces us to study the choices we make as consumers: necessary or desire? The boundary between art and commerce is beautifully presented here… we live, after all, in a financial-centric society!