Culture

Bringing back Murano’s glory

From Stories of Italy, the Crackle Collection of Vases and Tumblers.

Image courtesy of: Stories of Italy

Murano, known as the “glass-blowing capitol of the world”, started by a string of events that began in the Middle Ages. The small island just a mile north of Venice has been home to the enormous gas furnaces since 1291. The furnaces were moved to Murano in order to contain and sequester the frequent fires that erupted. The government decried that the workers and their families remain cloistered on the island.

As a result, glass dynasties became a step below royalty as they elevated glass’ aesthetic and started designing chandeliers and mirrors in addition to vases and simple accessories. These renowned glassmakers were monitored so that their trade secrets would not leak…creating a sort of monopoly as globalization began to threaten.

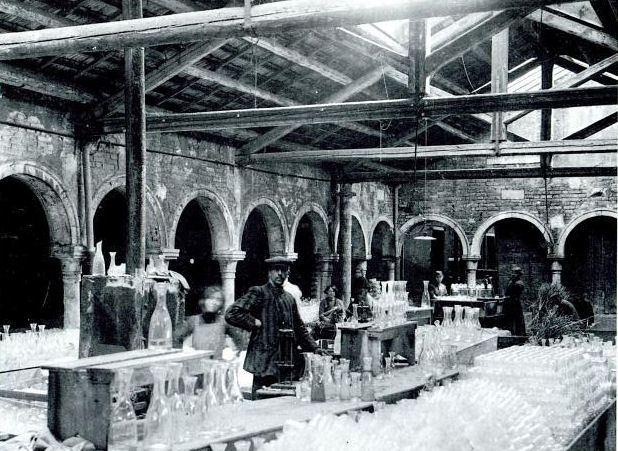

The Fratelli Marietti Milan bottle factory in the mid-1880’s housed inside the Ex Chiesa di Santa Chiara.

Image courtesy of: Santa Chiara Murano

Venetian merchants were able to keep the secrets of glassmaking they had learned from the Muslim world for more than a century. However by the 18th-century, France, Germany, and England had perfected their own glass industries.

Fifty years after Murano’s demise, local industrialists attempted to bring the island back to its former glory. It took until after World War I for the industry to refine it’s purpose and to be reborn as the palace for “glass artistry.” The Murano glass of the Middle Ages was either clear or pale; however in 1921, Paolo Venini, a Milanese lawyer, and Giacomo Cappellin, a Venetian antiques dealer, decided that it time to energize glass with vibrant colors.

From Luca Nichetto’s Plastic + Glass = Plass Collection for Foscarini.

Nichetto applies “high tech” to the tradition of ground glass by using rotational molding to create a lightweight polycarbonate diffuser.

Image courtesy of: Moco Loco

Venini hired Carlo Scarpa in 1932; soon Gio Ponti join the team to create the shapes and colors we now associated with Murano. Scarpa and Ponti (both of whom would become legends in Italian architecture and design) began frosting the glass with translucent orbs and ribbing, effects that resemble distressed wood or “fish scales,” and explosive colors. Those pieces from the “Golden Era of Murano Glass” remain desired by collectors; however the decades that followed were not lucrative for the island’s glassblowers.

By the later part of the 20th-century, the island had lost more than half it’s operations; only 100 companies remained. Unfortunately, the remaining glass-makers are older than 70 and the younger generation of artisans is simply uninterested in spending their days in front of a 2,000-degree oven and on an unexciting island with a population of less than 5,000.

Luckily, a group of artists, some with personal ties to the island, have realized the uniqueness of Murano. In addition to the generations of tradition that is tied to the island, glass-blowers say that Murano glass stays hotter for longer due to the ingredients. The proportion of sodium oxide, nitrate, and other minerals changes the very nature of the material, enabling the glass to be worked more deeply. Luca Nichetto, a designer with studios in both Stockholm and Venice and the grandson of a master blower and son of a mother who decorated the works as they emerged from the kilns says (courtesy of an interview with Nancy Hass for The New York Times Magazine), “I have Murano in the blood. I explain to people I work with all over the world what it is to have these craftsmen, how it is not like anywhere else.”

From a Special Collection for Stories of Italy, orbs for Pierre Gonalons’ iconic King Sun lamps. This glasswork uses the Macchia su Macchia technique.

Image courtesy of: Stories of Italy

Enter Dario Buratto and Matilde Antonacci, the 39-year old duo that runs Stories of Italy, the Milanese store that works solely with Murano’s artisans. The pair met in 2000 while studying in Florence and worked in Italy’s fashion scene until they were drawn their country’s glass-blowing traditions.

Opening a studio in 2015, they travel to Murano on a weekly basis and work with selected glass-blowers to create vases and glasses. Buratto says,”These are people who don’t read email, who maybe stopped going to school at 15 to become a master at this. They want you to work side by side with them. They are your hands.”

The Opale Collection by Stories of Italy.

This collection comes from the Murano secular tradition, a technique that dates back to the 16th-century. The design is created by melting together white opaline glass flakes onto a transparent crystal base. This technique creates a snowy surface that is filled with varying transparencies.

Image courtesy of: Stories of Italy

We hope that slowly, more companies such as Stories of Italy will realize the value that the island of Murano holds. They understand that deep inspiration comes from the historical and cultural heritage of Italy. The “everyday objects” that they design are more than beautiful, they are “tools of communication” with their own stories. Blending art, craft, and design; the designs the company produces capture Italy’s most revered traditions all the while playing and experimenting with materials and their artisans’ abilities.

It is the strong and established relationship with the local glass-blowers that makes the works art. For these masters, their job is really their life… they hold the history of Italy in their well-equipped hands. As Buratto and Antonacci say, their hope is that their creations represent a “small continuation to the Italian heritage preservation. We hope (and think) so also!