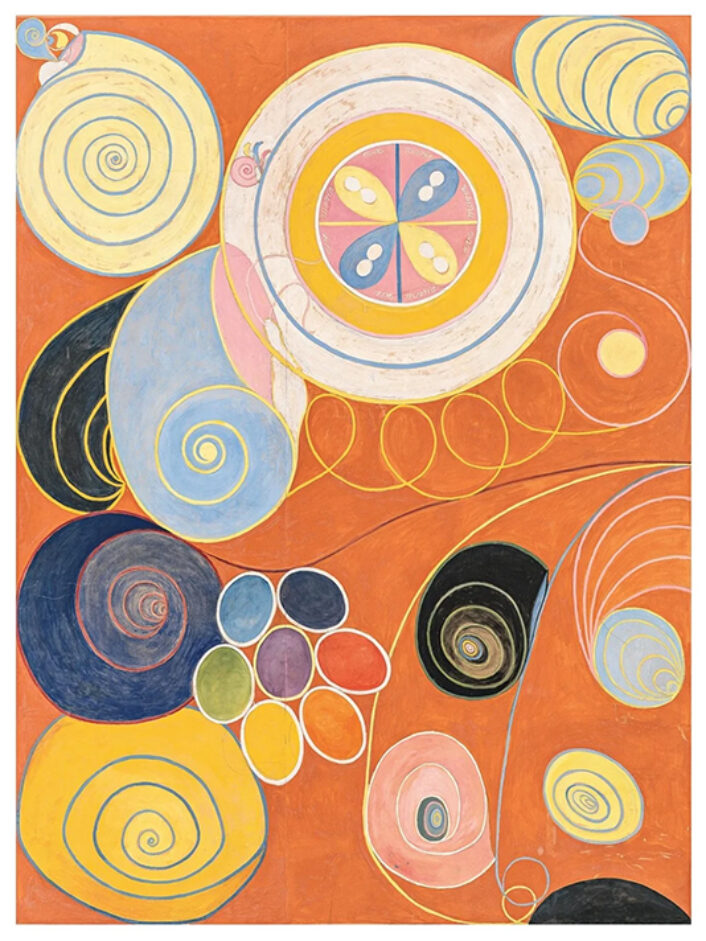

Fine Art

Giacomo Balla

“Speeding Automobile,” 1912.

Written by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the original Futurist manifesto complimented new technology; especially that of the automobile’s speed, movement, and power. Sadly though, the Futurists also believed strongly in violence and war; they exalted for the demolition of all cultural institutions such as libraries and museums.

Image courtesy of: Cardi Gallery

Giacomo Balla, born in Turin, Italy in 1871, was one of the leading members of Italy’s Futurist movement. A radical thinker among radical thinkers, Balla was self-taught and deeply influenced by Cubism. At the age of 24, the artist departed for Rome; five years later, he spent several months in Paris. It was there that he visited the “Exposition Universelle.” Balla loved his life in Paris, viewing it as one of the world’s greatest metropolises. In Paris, he was able to study the Neo-Impressionist paintings of French artists, among which were Georges Seurat, Henri-Edmond Cross, and Paul Signac.

Balla had a complicated political past, he was one of the original signers of the Manifesto of the Futurist Painters. The 1909 doctrine is considered to be the official founding document of the Futurist movement… those who signed the manifest agreed that the goal of the Futurists was to disregard art from the past and to bring in a time that rejects tradition and celebrates change, creativity, and originality in society and culture.

“Velocità di motocicletta (the speed of the motorcycle),” 1913

Most of Balla’s pieces have a Cubist perspective to them.

Image courtesy of: Cardi Gallery

Balla was especially infatuated with one specific piece of transportation- the automobile. The Futurists called it (courtesy of Cardi Gallery), “more beautiful than the Nike of Samothrace.” An important body of Balla’s work is a series of drawings and paintings that explore velocity and mechanical speed. Unintentionally, the moving car became a symbol for the modern world.

Geometric shapes, sometimes in fragmented forms, dominated canvases. Hoping to portray the dynamic mechanics, Balla began deconstructing each broken form into a geometric form. In essence, “Rectangular lines are superimposed with round shapes of wheels that in dynamic succession are repeated across the canvas.”

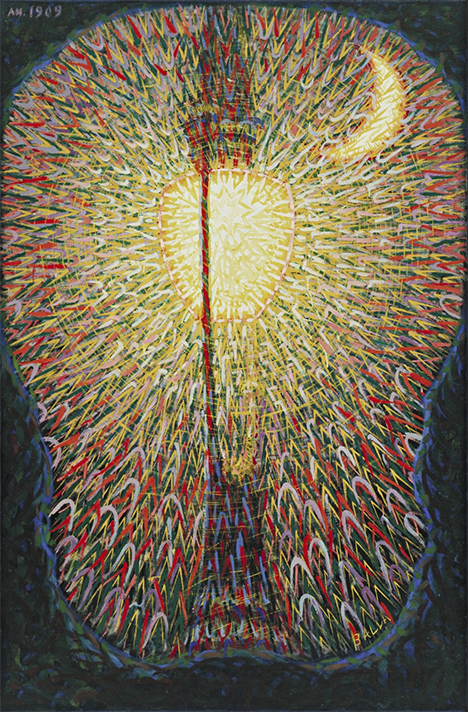

“Street Light,” 1910-11 (dated 1909). Oil on canvas.

Image courtesy of: Smart History

The Futurists were inspired by Europe’s rapid industrialization. Innovations were happening throughout the continent, and industrial cities were celebrated. The movement deemed that Italy’s culture was decaying because of the importance placed upon tradition. They further believed that humans would be freed and enhanced by art and thus, the concepts they considered of utmost importance were portrayed since they “bridged the avant-garde and life, feeding the Futurist notion of the “opera d’arts total” (the total work of art).

A painting that demonstrates the Futurist’s ideals is “Street Light.” Rejecting what had been considered classic subject matter, Balla painting an electric street lamp. At the time the piece was painted, this innovative piece of technology had just arrived in Rome. More than just highlighting technological advancements, this was also a way to spotlight that Rome, an ancient city, was moving on from its past.

“Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash,” 1912. Oil on canvas. Displayed in the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy.

Image courtesy of: Britannica

Balla was very interested in movement and conveying a sense of speed and urgency. These principles were commonly portrayed in his paintings, and they are in line with the Futurist Movement’s interest in energy. One of Balla’s most familiar works is “Dynamic of a Dog on a Leash.” This 1912 painting attempts to mimic a woman walking a dachshund. In this painting, the locomotive is the dog… his legs and the leash flickering are featured as a halo of dashes and short lines.

The effect of chronophotography was quite influential on Balla, especially the motion that Etienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge portrayed twenty five years earlier. Although these pioneers used groups of cameras to showcase movement, Balla illustrates the same notion in a different way. Rendering motion by simultaneously showing aspects of a moving object, the artist appears masterful in illustrating movement.

Cassina Paravento Balla

This piece comes in two color iterations: cinnabar, citron, and deep forest and shades of blue and sage green on a white background.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times Style Magazine, photographed by: Diego Mayon

Balla’s works have become mainstream; the best example is the original sketch of the Paravento Balla. Painted by the artist in 1917, the drawing is of discarded photographs that Balla etched onto a folding screen which he colored with tempera and pencil. This beautiful design sat unpublished for more than fifty years until it was published by Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco in a book titled, “Balla: futurist reconstruction of the universe.”

The drawings are a great indication of Balla’s use of color and chromatic combinations, which is why Cassina jumped at the chance to reproduce the partition. Collaborating with Balla’s heirs, the Italian luxury brand comprised three panels in differing heights and widths from honeycomb wood and joined together by satin brass hinges. Silk-screened on both sides, the colors are those Balla himself specified. If nothing else, this happy piece illustrates that the future has indeed arrived!