Fine Art

Judit Reigl

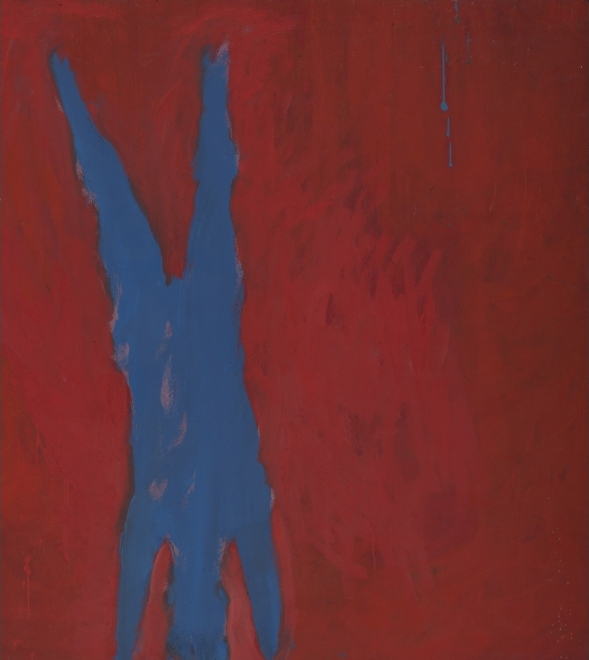

“New York,” 2005. Oil on canvas, on display at the Musee D’Art Moderne De Paris

Image courtesy of: Musee D’Art Moderne De Paris

Judit Reigl was a Hungarian artist who studied painting at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest in the early 1940s. She was fortunate to receive a scholarship from the Hungarian Academy of Rome in 1946; afterwards, she traveled to Italy for two years.

Upon returning to Hungary in October 1948, she found her homeland overtaken by a Soviet-style authoritarian regime. Reigl realized that she needed to leave Hungary. However, it took her nine attempts to escape her country. On the ninth try, Reigl walked over a minefield at night in hopes of reaching the express train from Budapest. Finally, she successfully crossed the Iron Curtain in March 1950, arriving in Paris a few months later.

“Outburst (Explosion),” 1956. This painting is part of a private collection in Hungary.

The painting mimics intimations of trauma such as one that intensifies in conjunction with the Budapest uprising in 1956. The abstract marks suggest tank tracks and shells bursting.

Image courtesy of: The Guardian

In Paris, Reigl teamed up with fellow Hungarian Simon Hantai who introduced her to Andre Breton. Breton was instrumental in putting together Reigl’s first solo exhibition in 1954. However, Reigl was quick to transition her art from Surrealism towards a more “action painting” approach.

During this time, Reigl worked on monochrome grounds which were brightly colored, yet marked with palette-knife and blade scrapings. Her abstract and physical approach was accomplished by hurling compounds of industrial pigment and oil on her canvas. During the drying process, Reigl molded them with metal devices into explosive marks. She often used her body as an “instrument of painting.”

“Center of Dominance,” 1958.

Image courtesy of: CR Fashion Book

A reintroduction to Henry Moore, who Reigle had met during her visit to Italy in the 1940s, ensued a lifelong relationship. The couple soon moved out of Paris and to the commune of Marcoussis; ironically, an area that was dear to Cézanne.

Gradually, Reigl’s canvases increased in size… and so did the involvement of her “entire body in action” as she painted. Her gallerist Janos Gat recalled (courtesy of The Guardian), “Reigl would reach for any tool at hand- a twisted length of curtain rod, the faceted stopper from a Channel No 5 flacon.”

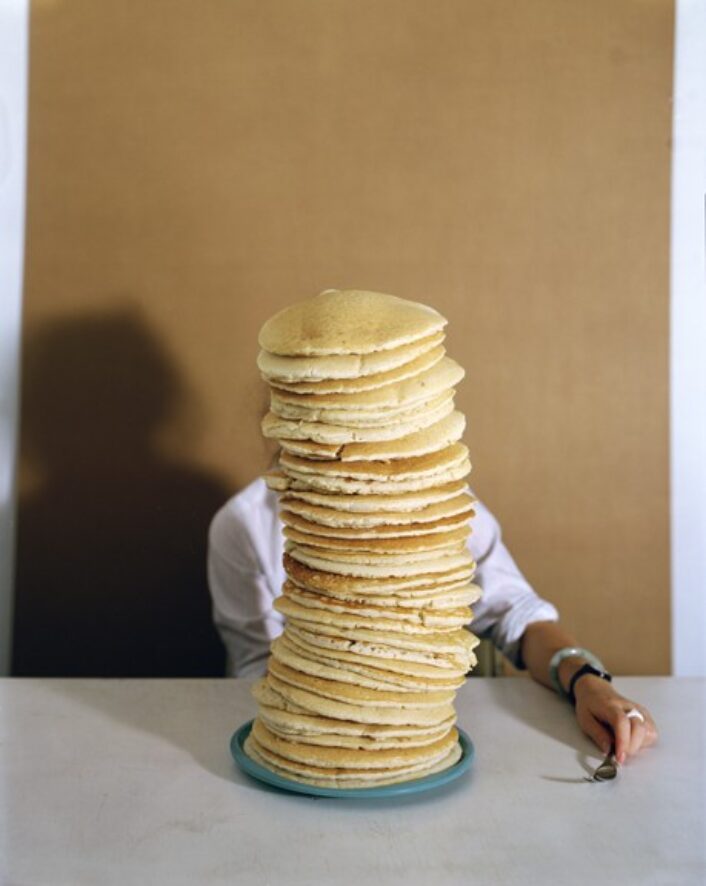

“Guano,” 1958-1962.

Image courtesy of: Judit Reigl

During the late 1950s and early part of the 1960s, Reigl began recycling a group of abandoned canvases that had previously covered her studio’s floor. The blobs and sweeps of paint that fell as she worked were repurposed. Reigl stood on the canvases and moved across them impressing the splashes and drips into the surface. In 1961, the artist returned to the “encrusted surfaces” and realized that they WERE artwork. She began to work with the canvases… scraping away the paint and forming striated markings that moved across the surface.

Specifically, “Guano” has a dark grey band across the outer edge with a lighter, variegated khaki section in the middle. This area overlays the darker one and both are textured by Reigl’s marks that were left as she worked and reworked the paint onto the canvas.

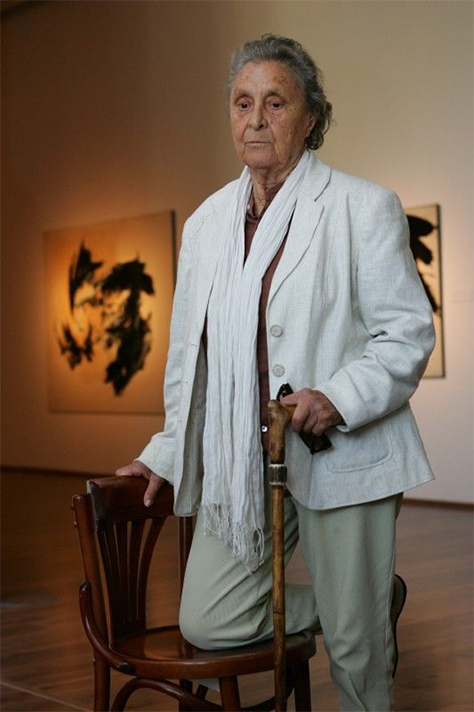

Reigl in front of some of her paintings. Sadly, the artist passed away in August.

Image courtesy of: CR Fashion Book

In an interview with Julia Cserba in “On Judith Reigl” in a catalog for an exhibition, published by Műcsarnok-Makláry Fine Arts from 2005, “My entire body took part in the work, “in the wake of my arms wide open”. I wrote in the given space with gestures, beats, impulses.”

We couldn’t explain or describe the process any better!