Culture

Old-school Works Progress Administration posters

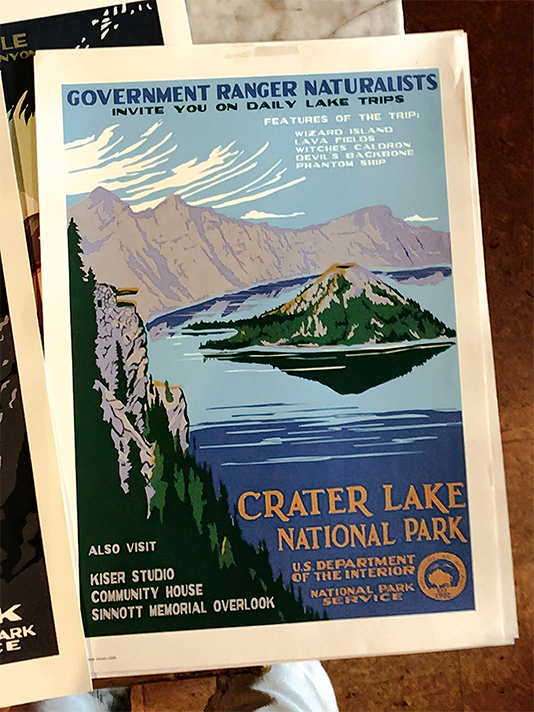

A contemporary design for Oregon’s Crater Lake National Park.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Annie Tritt

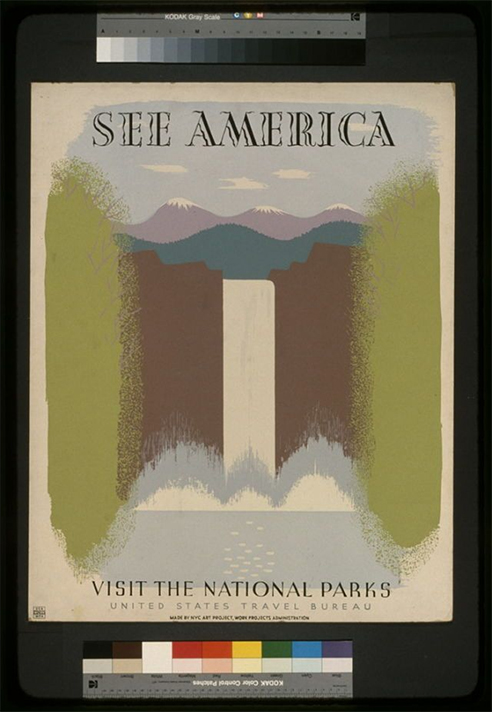

Back in the 1930’s and 40’s, Works Progress Administration (W.P.A.) artists designed 14 posters for some of the best known parks and monuments. After the Great Depression, the New Deal’s WPA hired Americans on a number of different public works. At that time, the Federal Art Project used 10,000 artists for eight years (1935-1943), including Diego Rivera.

The artists however, did not consider this glamorous work, earning roughly $23 per week. The artists worked on several projects at one time, similar to today’s freelancers. Many of the posters produced showed global influences such as the Bauhaus designs from Germany and drawing styles reminiscent of Mexican murals.

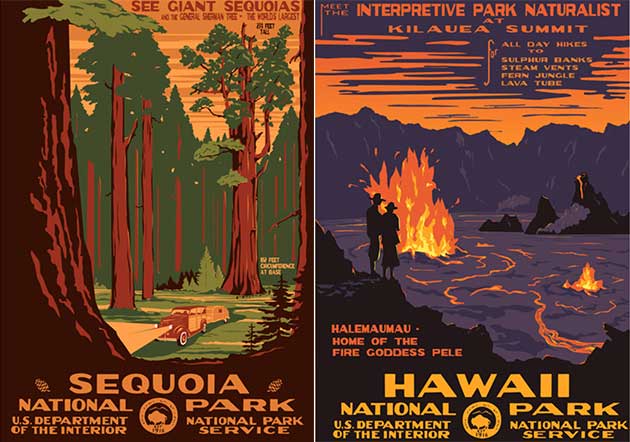

Doug Leen and Brian Maebius’ “Sequoia” (2007) and Hawaii (2007)

The program was extended to the National Park Service in 1938, it closed in 1941.

Image courtesy of: Harmen Liemburg

At that time, the National Park Service was 19 years old and the parks were not as popular as they currently are. Following the Depression, many did not have spare funds to travel the country; in addition, the country’s highway system was in in poor shape. The cumulation of these two factors attributed to the fact that Americans were not ambitious about traveling to public lands. The Federal Art Project (F.A.P.) began advertising the parks so that the potential visitors could see their value.

Western Museum Laboratories, a work space for several W.P.A.-funded projects, put out a catalog and thirteen national parks ordered 100 copies apiece. Sadly, of the 35,000 posters created during this time, only 2,000 were found and properly catalogued. From that number, only a small fraction were national park prints.

Doug Leen with two of his reproduced posters. Leen has nicknamed himself, “Ranger of the Lost Art.”

Image courtesy of: Live on Green Pasadena

For the past almost three decades, Doug Leen has taken it upon himself to ensure that the W.P.A.’s national park promotional posters do not permanently disappear. When he was a ranger at Grand Teton National Park at the Jenny Lake Ranger Station, he saw a “Meet the Ranger Naturalist at Jenny Lake Museum” poster. Considered trash, he took the poster home. In 1992, Leen moved to Alaska and years later, he got a call from a bookstore manager in Grand Teton who was seeking suggestions for a way to commemorate Jenny Lake Museum. As luck would have it, Leen went back to the antique poster hanging on his wall.

Leen called upon Mike Dupille to reproduce the poster; however the artist realized the importance of old silkscreen as a rare art form. The W.P.A. posters were the first examples of mass producing using this technique. The long and time-consuming process involved extruding inks from cloth of one color layer individually… the end result was a hand-drawn poster with a stark vibrancy.

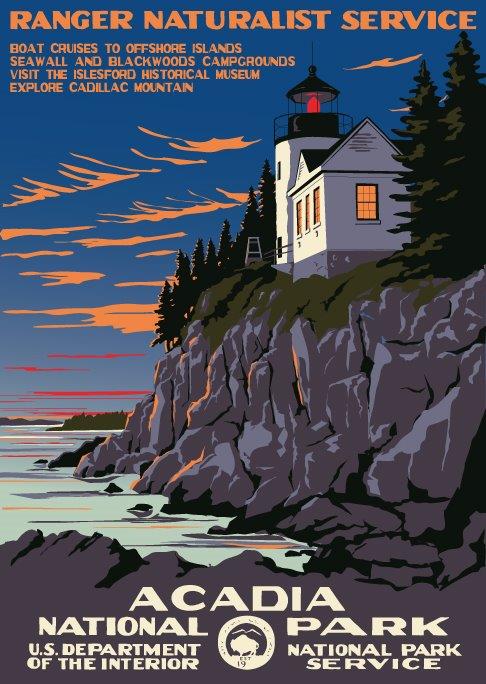

One of the contemporary designs of Acadia National Park features Bass Harbor, the iconic lighthouse on Maine’s coast.

Image courtesy of: Ranger Doug

Leen was curious about other parks and their corresponding prints so he called Tom DuRant, the archivist at the N.P.S. Harpers Ferry Center. DuRant found a set of black-and-white negatives of 13 of the 14 W.P.A. national park poster designs.

Soon, Leen started a company that recreated each original design using the original silk-screen method. He hired Brian Maebius to create posters for the national parks that never had one, these were designed in the same style of a limited color palette and matching font. At the same time, Leen began an exhaustive search for the 1,400 original national park posters copies, circa 1943. The record-keeping behind the beautiful prints was awful and since the prints technically belonged to the government, they were rarely signed.

One of the posters created by the W.P.A. from the roughly (approximately 6.7% of the country’s GDP in 1935), $4.9 billion used to hired the millions of unemployed citizens for public works projects.

Image courtesy of: Popular Mechanics

There are still two prints that Leen has not found: Wind Cave Nation Parks and Great Smoky Mountain. He is offering a $10,000 reward for either! Today, Leen’s posters are sold on Ranger Doug’s website and in park shops (the majority of the profit goes to help the national park, which are severely underfunded).

About why these prints are so special, Leen said (courtesy of Popular Mechanics), “In the silkscreen form, they are vibrant. A lot of people are printing these on little on-demand printers now. Printers have become so cheap, these giclee printers and their ink jets and whatnot, but you know, in a couple years they fade and they look horrible and people send them back to me to figure out where they went wrong.”

Thanks Ranger Doug for keeping a special part of our national history alive… and thriving!