Culture

Peggy Guggenheim’s Tribal Art Collection

From this year’s show at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, a D’mba headdress by a Baga artist in Guinea. The piece stands in front of a 1939 Picasso portrait. Often, Guggenheim paired her modern art pieces with tribal art.

Image courtesy of: 1st Dibs, photographed by: Matteo De Fina

Everyone knows about Peggy Guggenheim’s collection of modernists such as Pollock and Picasso; but her tribal art collection is equally fascinating. The storied heiress-turned-art-patron was always generous with her collection, intent on sharing it with the public. In 1951, she opened her palazzo on Venice’s Grand Canal from Easter through early fall for three days a week in order to allow people to stroll through her private rooms and see all of her amazing artwork.

Those who pursued Guggenheim’s home were lucky enough to see works by the likes of Alexander Calder, Wassily Kandinsky, and Leonora Carrington. By this point in time, the heiress was already considered a champion of Cubist, Surrealist, Dada, and Abstract Art. However, those fortunate visitors were also privy to some of Guggenheim’s most beloved, yet less-celebrated, treasures which included her collection of African art, Oceanic art, and the art of the indigenous people of the Americas.

Left- seated male figure by an unknown Dogon artist from the N’duleri region in Mali from the first half of the 20th century.

Right- Peggy Guggenheim with the Dogon figure (above) in the entrance foyer of her Venice palazzo, “Palazzo Venier dei Leoni.” An Alexander Calder mobile hangs from the ceiling and behind Guggenheim is Picasso’s 1937 painting, “On the Beach.”

Image courtesy of: IMO DARA, photographed by: Matteo De Fina (picture #1)

To say that Guggenheim elevated the stature of tribal art would be a vast understatement. Displaying “non-Western” art prominently in her palazzo, she was one of the first to showcase how modern masters habitually borrowed inspiration from “primitive” forms.

For the time, this was a very fashionable interior decorating scheme; but it proved to be an art history lesson as well. Guggenheim loved her objects and was often found rearranging her favorites; yet, she was always cognizant that the formal connection between modern and ancient remain obvious.

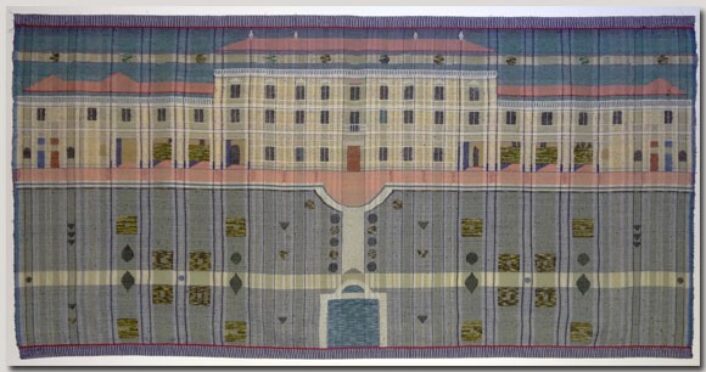

Palazzo Venier.

Guggenheim escaped Paris just days before the city was invaded by the Nazis. The Jewish, American-born heiress migrated to Venice in 1948, and she purchased the 18th-century palace in 1949. The palazzo was designed by the Italian architect, Lorenzo Boschetti… instantly, the stone building was turned into a cultural haven!

Image courtesy of: The Educated Traveller

Many of Guggenheim’s tribal objects were originally used for ritual purposes, mainly funeral ceremonies. Some of these pieces were part of a recent exhibition, “Migrating Objects: Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection.” The show, curated by Guggenheim’s granddaughter, Karole Vail, opened with 35 pieces. Vail has been overseeing the Venetian Palazzo since 2017 and has said of her mission, “Part of the educational mission of the museum is to highlight lesser-known aspects of the collection.”

Guggenheim died in 1979 at the age of 81; at that time, her collection became part of the foundation that Solomon R. Guggenheim, her uncle, founded in 1939. Sadly, some of her most personal belongings, including her non-Western art collection, were put into storage. Thanks to Vail, the objects are now out of their hiding places and in the public eye.

Guggenheim and her beloved Lhasa Also dogs on the roof of Palazzo Venier.

Image courtesy of: The Educated Traveller

The route that lead Guggenheim to begin collecting tribal art is an interesting one. She moved to Venice after closing her fabled New York City modern-art gallery, “Art of this Century.” Upon returning back to New York City, she became focused on buying more contemporary art. However, the climate had changed dramatically. Guggenheim said, “I was thunderstruck the entire art movement had become an enormous business venture.”

This caused her to look elsewhere, as she found herself “priced out” of the modern-art market. She explained, “In the next few weeks I found myself the proud processor of twelve fantastic artifacts, consisting of totem poles, masks, and sculptures from New Guinea, the Belgian Congo, the French Sudan, Peru, Brazil, Mexico, and New Ireland.” A new collection was founded!

Masks:

Left- Salampasu artist, in what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Middle- Tatanua mask (malangan) by a Madak artist, in Northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea.

Right- a Toma or Loma artist, in what is now Guinea.

Image courtesy of: 1st Dibs

It is clear that Guggenheim was ahead of her time and much more adventurous than many other collectors of her era. It was not until 1957 that the Museum of Primitive Art was established by Nelson A. Rockefeller, across the street from MOMA. At the time, Rockefeller’s collection of indigenous art, African Art, and Oceanic Art included a few objects that Guggenheim fell in love with and would later acquire for herself.

Guggenheim was never as vocal about this collection as she was about her European and American paintings and sculptures. However, it is clear the pieces were very important to her. Vivian Greene, the exhibition’s main curator said, “She wrote about loving the work while she was collecting it,” says Greene. “She corresponded with a man who collected non-Western objects, Robert Brady, a Barnes student who settled in Cuernavaca. She writes, ‘I’m so glad I started collecting primitive art.” Hopefully, the newfound attention it is receiving will enable it to find its proper place in the hearts of art lovers everywhere.