Architecture

Richard Gilder Center at the American Museum of Natural History

The museum’s expansion is taking place on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

Image courtesy of: World Architecture

Officially, Richard Gilder Center at the American Museum of Natural History opened last month… however parts of the museum have been opening slowly over the past several months. The 260,000-square-feet expansion of the American Museum of Natural History in New York officially opened on February 17th.

In 2014, the museum first announced plans for a major expansion devoted to science . The expansion’s center, the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education and Innovation, ensued a $431 million tab. Today, the expansion is especially important as we live in a world that is affected by climate change and catastrophes such as the coronavirus pandemic. Courtesy of The New York Times, Ellen V. Futter, the museum’s president verbalized the importance of the “gap in the public understanding of science at the same time when many of the most important issues have science as their foundation.”

Organic shapes and natural light are the building’s hallmark features.

Image courtesy of: Wall Street Journal, photographed by: Martien Mulder

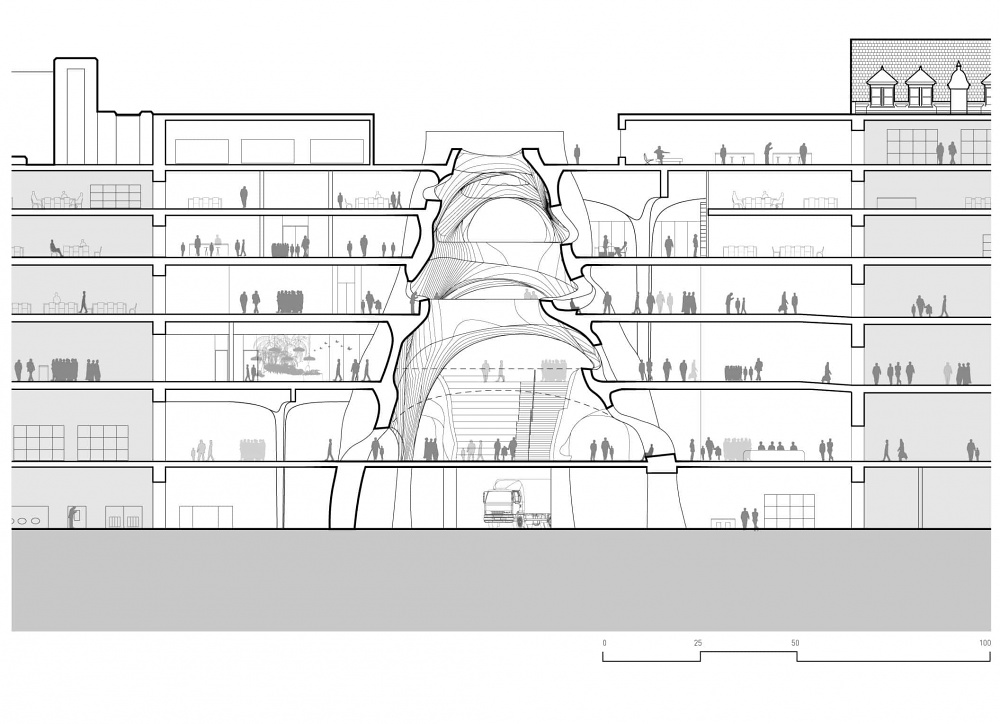

Designed by Jeanne Gang from Studio Gang, the undulate stone and glass exterior forms an organic amorphous, reinforced concrete structure. The curving exterior surfaces are (courtesy of Architect Magazine) “warped and biomorphic;” and “influenced by the form-making forces of ice and water, expressed through an innovative concrete blend; its cavernous nooks and crannies give the visitor a thrilling sense of discovery.”

Studio Gang’s latest building resembles a high-rise that is carved by the water and the wind rather than something designed via paper and architecture programs. The museum entrance is a flow through an opening between existing buildings… as such, the 65-foot-tall glass edifice waits to be explored.

A rendering…

Image courtesy of: Studio Gang

It was officially ten years ago that Studio Gang landed the commission for this project by being the winning bid in a competition. In line with the architectural firm’s pillars of their interdisciplinary practice, the design integrated aspects of architecture, nature, science, and art.

Ultimately, the design owes tribute to the American Museum of Natural History’s earliest dioramas by Carl Akeley. A big-game hunter, taxidermist, and inventor who worked at the museum from 1909 to 1926, Akeley invented a method of scooping plaster and papier-mâché over wire armatures to create lifelike creatures. Taking cues, Gang’s design hoped to minimize the distance between the museum’s visitors and the natural world… if only just a bit.

The building’s exterior is clad in Milford Pink Granite… the same stone that covers the museum’s entrance on the opposite side.

Image courtesy of: Studio Gang

A central exhibition hall (courtesy of The New York Times), “forms the spine of the new wing, and it forges an immediate connection with the material on display: Warped and biomorphic, the structure’s design is influenced by the form-making forces of ice and water, expressed through an innovative concrete blend; its cavernous nooks and crannies give the visitor a thrilling sense of discovery.”

With the added exhibition spaces, there is a new section fully devoted to insects and one set aside for butterflies. In addition, there are educational spaces and a lecture hall… all of these are centered around the main entry foyer and made accessible through the “catacomb-hollows of the concrete core.”

The Invisible Worlds Theater while under construction. The 360-degree theater is just one more way the immersive environment melds art with science.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Timothy Schenck

Improving the old building’s circulation was one of the main goals; in such, thirty new connections within the ten existing buildings were created. Visitors are now able to move around much more freely. Futter concurs, “We’ve been plagued with dead ends for years. They are gone.”

Contrary to most museums’ designs, this structure does not have an imposing aura; rather the opposite, floor-to-ceiling classroom windows allow visitors to look in and about. In essence, the big windows do much more than let in light, they serve as an invitation to come and visit.