Architecture

Taipei Performing Arts Center and the spherical playhouse

The Taipei Performing Arts Center.

Image courtesy of: CNN, photographed by: Chris Stowers

Nine years after originally scheduled to open, the Taipei Performing Arts Center opened in Taiwan. The landmark building was designed by the Dutch architecture studio OMA. Despite construction delays and budget concerns, the new venue is (courtesy of CNN), “radically rethinking the way theaters operate.”

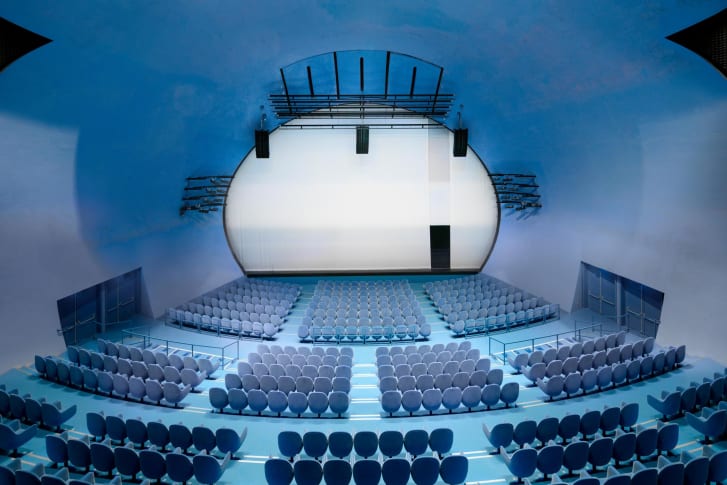

The 635,000-square-foot, $223 million project opened in August with three venues: the spherical 800-seat Globe Playhouse, the 1,500-seat Grand Theater, and the 800-seat, multi-form theater for experimental performances called the Blue Box.

The design was influenced by Taipei’s (courtesy of Dezeen), “appetite for experiment.”

Image courtesy of: CNN, photographed by: Boo-Him Lo

The interesting exterior has many fronts which OMA designed by inserting three theaters into a central glass-clad cube. Clearly, the most distinctive feature is the spherical silver auditorium that is clad in corrugated glass. According to OMA, the comparison is to “a planet docking against the cube.” OMA’s founder and chief architect, Rem Koolhaas said, “In the early part of the 21st century, there has been… an apparent obligation to make buildings stranger and stranger. In this case, we simply — almost mathematically — took the absolute outside shapes of each of the components that we were obliged to combine… that is the only spectacle.”

To continue, David Gianotten, the firm’s managing partner and also an architect said, “They are two very well-known shapes: a cube and a ball. But when you combine them, they create something that wasn’t there before.” Koolhaas and Gianotten began tinkering with design ideas in 2008.

This is OMA’s first commission in Taiwan.

Image courtesy of: OMA

IN 2009, OMA won the competition for this highly-anticipated complex along with the Taiwanese design studio, Kris Yao Artech. Commissioned by the Taipei City Government, the structure’s intent is to support local performing arts groups. Originally, the hope was that the building would be completed by 2013; however, construction was delayed until 2012.

Pushing the envelope of “conservative performing arts venues,” the design includes three separate theaters that all share a common backstage space. The reasoning for this was two-fold: one reason is for efficiency as the architects wanted to save space in the busy neighborhood, and the second reason was to encourage interaction between the other theaters’ actors, staff, producers, and audience members.

In traditional venues, there is no “connection” between the different performances and performers. Alex Wang, the center’s CEO said, “To us, what was really interesting was having all these types of energies — visitors coming in anticipation, people who are creating, people who are performing — all together.” The sky’s the limit indeed.

Up close…

The center opened with a beautiful performance by the Taipei Symphony Orchestra. This show kickstarted a season of 37 productions scheduled across the three different theaters.

Image courtesy of: Behance

An important element is (courtesy of Dezeen), “the Public Loop, a walkway that runs around the theater’s production and backstage areas.” Additional successes include lifting the auditoriums using stilts and building a landscaped plaza beneath the building. In essence, this serves as an additional performance space… one that is open to the public.

The unique juxtaposition of spaces means that the theater culture and the street culture can coexist; even more than coexist, both can learn from one another. Gianotten said, “For us, this mix of cultures aptly captures the energy of Taipei, a city always open to changes.”

One of the “walkways.”

Image courtesy of: OMA

An added bonus is that the building is open to the public whether or not someone has a ticket. The walkway below is lined with portal windows that provide views into areas that are commonly hidden. Further reinforcing this fact, Koolhaas said “that the project’s ‘distinguishing feature’ is neither the unconventional layout nor the giant sphere colliding with its facade— it’s the public spaces created around the venue.” We love it all!