Culture

The artistry behind Japanese Noh masks

The Tokyo-based Shuko Nakamura wearing one of her amazing masks, “Migawari no Ki,” 2020.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times Style Magazine, photographed by: Bo Duke

Once in a while, we like to revisit upon unusual artisans… As we reflected back on the Japanese art of Noh, it became clear that we needed to discuss what is one of the world’s oldest surviving theatrical forms of art and the artisans who make it happen. When Noh began, the highly-specialized type of entertainment often included ceremonies conducted by villagers who were thankful for the harvest.

The origins of Noh theater goes back to the thirteenth century and the masks associated with the art belong to a highly-developed theatrical tradition. Initially, the purpose was religious; but now, the Japanese masks are part of an art form that is important to keep alive.

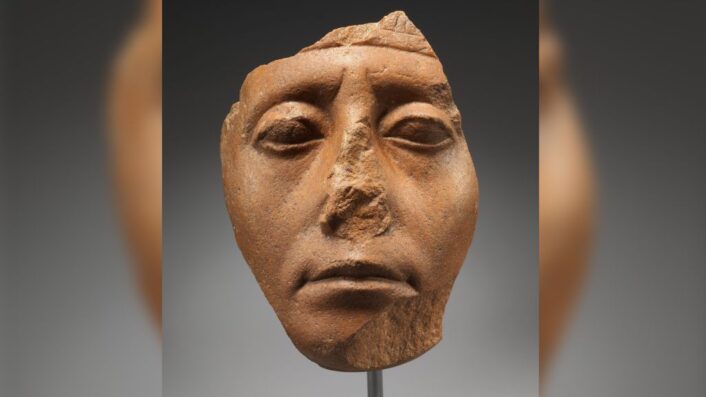

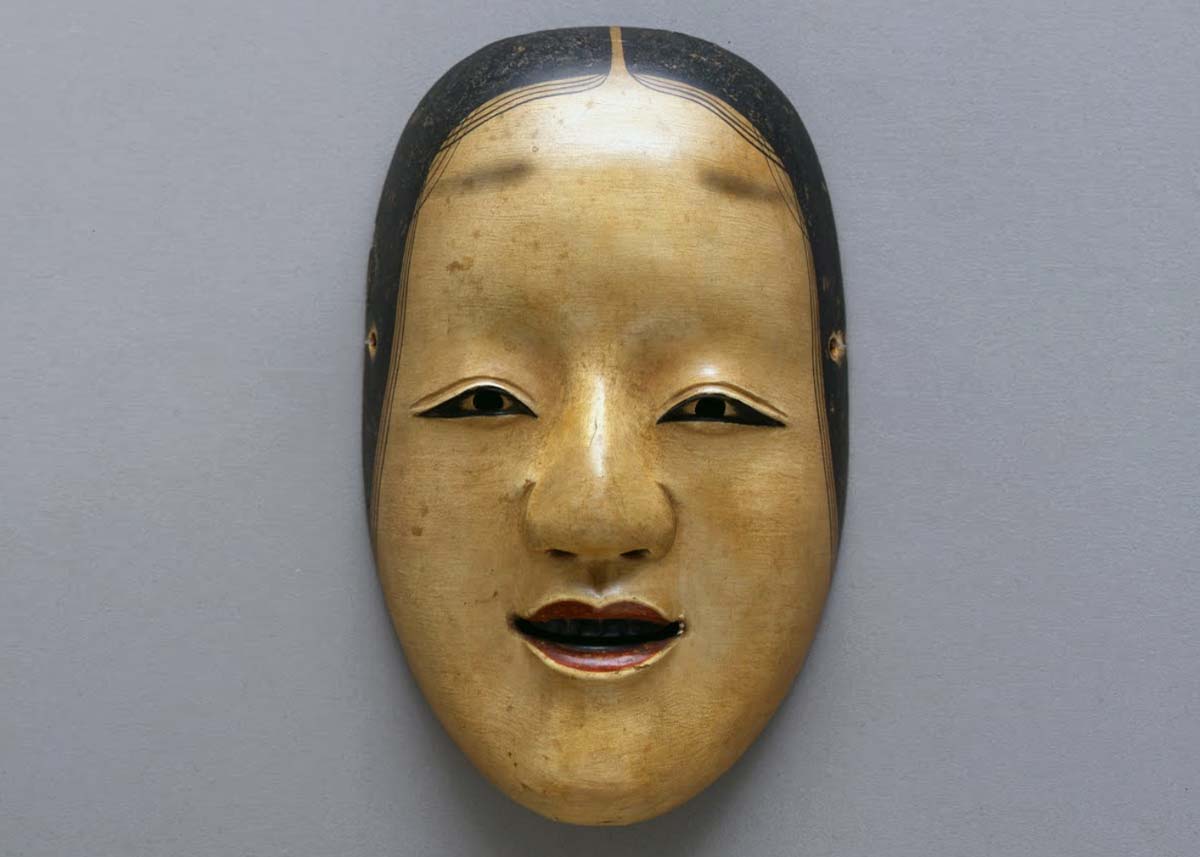

An 18th-century Onnamen Noh Mask. Onnamen masks represent wise women (attributed to the gold-rimmed eyes). This mask, with a slight smile, portrayed a character that is in love.

Image courtesy of: Japan Objects (courtesy of: Fukuoka City Museum)

The distinguishing feature of Noh were the performers’ carved masks. The different masks represented the various characters. Unique to these masks was the lack of emotion portrayed… a static face that seems to come to life depending on external factors such as (courtesy of The New York Times Style Magazine article by Hannah Kirshner) “the angle of the performer’s head and the way the light hits its features.”

Traditionally, women were forbidden from acting in Noh; their parts were played by men who wore women’s masks. Following World War II, women were allowed to perform Noh professionally; some women were even featured in leading roles.

Nakamura at work.

Image courtesy of: Mitsue Yuya

Up until relatively recently, this was a craft that was handed down from father to son. The skilled artisans use hinoki cypress wood and carve out high reliefs that are hollowed out and primed with a white mixture made from crusted oyster shells and animal glue. In addition, the gold or copper paint gives the eyes and teeth an otherworldly essence.

In the 1980’s, Mitsue Nakamura began to learn the sacred craft. It often takes the Kyoto-based artisan an entire month to complete a mask. Since ancient-looking masks are those most desired by actors, Nakamura often creates shadows that she smudges into the faces’ contours or scratches the paint with bamboo to achieve a weathered appearance.

These days, Nakamura has four female artisans that train under her… learning the unique and challenging form of mask carving for Noh theater. As more females enter the realm of mask-making, they add subtle changes in the traditional art form. Many of these slight alterations have to do with the artisans’ personal connections to Noh.

No longer are there only sixty basic types of Noh masks; many believe it is the contemporary women carvers who are changing the face of this centuries old tradition.

Nakamura wears her very own “Ikkaku Sennin,” 2020.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times Style Magazine, photographed by: Bo Duke

Some female artisans however are making bigger and more subtle changes in traditional marks. Nakamura, for example, makes masks from clay and paper rather than from wood. A stark departure for the purists, the artisan shows her respect for Noh by calling her creations “creative masks.”

Courtesy of The New York Times Style Magazine article by Hannah Kirshner, Nakamura clearly sees a place for her work “that expand the boundaries of Noh’s conservative culture. ‘Of course, the best masks are those used onstage,’ she says, ‘but I think we should also make Noh masks that can stand on their own.”