Culture

The Story Behind Guatemalan weavers

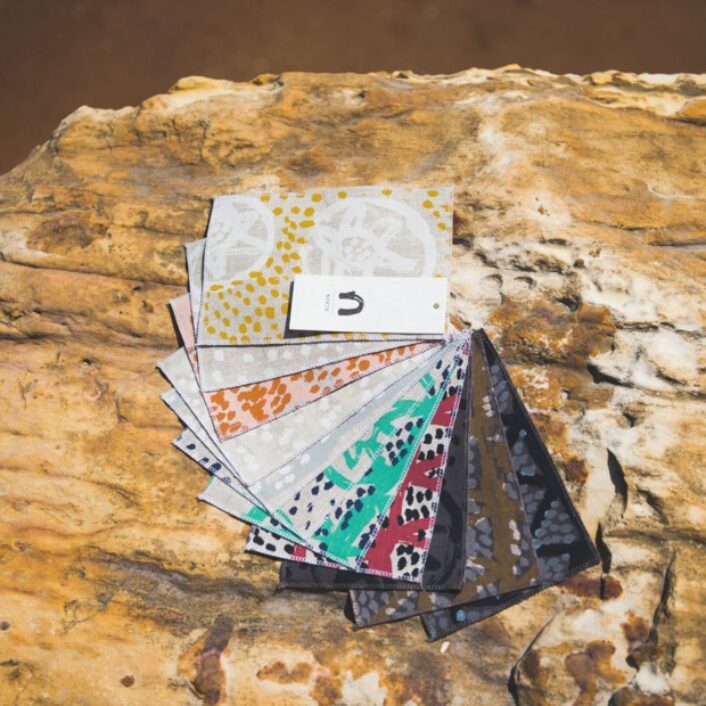

Blankets and scarves for sale in Guatemala.

Image courtesy of: The Discoverer, photographed by: Fiona Mokry

The country of Guatemala is steeped in tradition, and part of that tradition is due to the country’s strong connection to the region’s Mayan heritage. Luckily, the country has always honored its rich past and their customs that have been celebrated for years.

One of the most important customs is backstrap weaving, a centuries-old art form that is still practiced among the local women weavers in many villages across modern-day Guatemala. Legend states that the Mayans first learned to weave 1,500 years ago by Ix Chel, the Mayan Goddess of the Moon, Love and Textiles.

Weaving pulls from the earth by using home-grown cotton and natural dyes from plants, bark, fruit, and vegetables.

Image courtesy of: House & Garden UK

Mayan women learn to weave in order to provide fabric for their homes and families. It has been noted that the wealthier the woman, the higher quality thread she uses and the more elaborate the designs she masters. There is obvious practicality in weaving clothing, towels, and baby wraps. However, as time went on, close inspection of a woman’s hand-woven products would determine her wealth and status.

For the weavers, this is as much part of their day’s domestic chores as caring for children and cleaning the house. Interestingly, over the centuries, each village would develop their own characteristic patterns and colors which portray their community’s identity… much like a language’s dialect. On an empty piece of fabric, the women would repeat geometric designs, stripes, animals, flowers, and birds using their practiced techniques!

A Guatemalan weaver using a traditional backstrap loom.

The Spanish colonists introduced the treadle loom in the 1530’s. This machine allowed weavers to work faster; however, it did not completely replace the traditional backstrap loom.

Image courtesy of: Galerie Magazine, photographed by: Gerson Cifuentes

The materials remain important! Cotton is still the most commonly used material in traditional weaving. It is cultivated and some is imported to the United States and Nicaragua. With the arrival of sheep, the Spanish conquistadors introduced wool to Guatemala; this material was also used in weaving. Up until recently, weavers colored the fibers with natural dyes that came from the earth’s organic materials. Today, many weavers purchase the yarn already prepared. This “shortcut” dramatically cuts down on the time-consuming process of carding, spinning, and dyeing the fabric. Chemical dyes and synthetic acrylic threads have gradually replaced the natural ones. It is quite rare to find weavers who still prepare their dyes and yarns in traditional ways.

What remains unchanged is the backstrap loom… this looks identical to how it appeared in Mayan ceramics which date back to 600-800 A.D. The elementary machinery is made of rods that loop around the weaver’s back as she sits on the ground in order to maintain the correct tension on the threads. The other end gets tied to a tree or a post

A textile at Rum Fellow Coyolate… in progress.

Image courtesy of: Galerie Magazine, photographed by: Gerson Cifuentes

The 36-year Guatemalan Civil War was the cause of 200,000 lost lives; the vast majority of which (83%) were Mayan. For these communities, the peaceful and traditional way of life was completely devastated. The war was a conflict between the right-wing government and supporters of the socialist idea of peasants’ rights to the land. Those who survived the guerrilla fights and mass ambushes were left with burned villages, no chance at education, and zero opportunity either presently or for the foreseeable future.

Via their grandmothers’ techniques that had been passed down, the villages’ women banded together and began weaving their identity back. Little by little, this manual labor occupied the survivors’ minds and slowly diminished their vivid, horrible memories. Luckily, this art also lead to a way for the women to feed their families.

A weaver working on a backstrap loom.

In 2005, a USAID external report estimated that there are between 700,000 and 900,000 weavers in Guatemala, most of which are indigenous women.

Image courtesy of: Revue Magazine, photographed by: Matt Day

Following the country’s Civil War, women weavers joined together and formed cooperatives as a way to ensure that they earn a fair wage for their artistry. It is common to see three generations of women weaving together. Often times, only the youngest family members speaks Spanish; the others usually speak one of the 21 native languages recognized in Guatemala.

Dylan O’Shea (and Caroline Lindsell) of the London-based “A Rum Fellow,” a studio dedicated to artisan textiles, rugs, and statement interiors unique for their colors and intricate patterns said, “That social mission is very much at the core of what we’re doing, but we also wanted to make sure that what we are offering is extremely beautiful and stands up in its own right. Then behind that product is a great story and a great mission.”