Fine Art

We celebrate Piet Mondrian… and there is a surprise

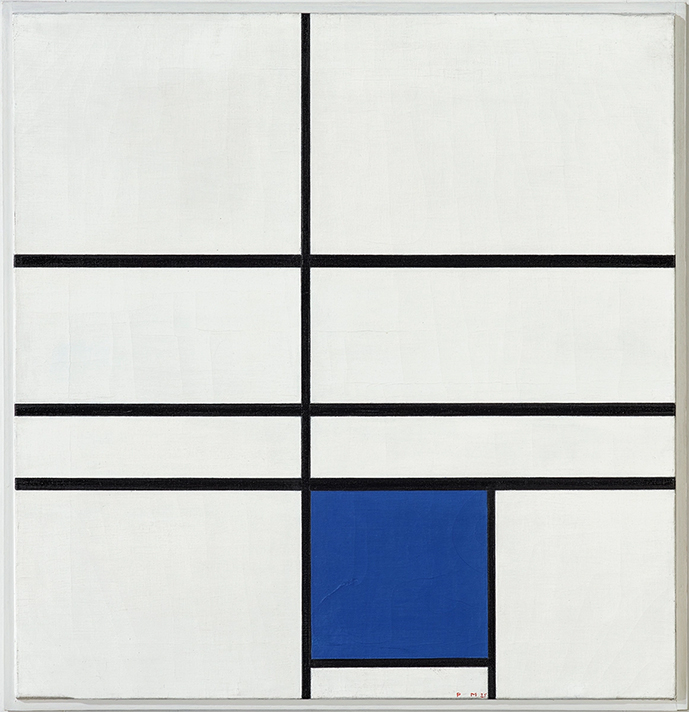

“Composition with Double Line and Blue,” 1935. Oil on canvas.

Dimensions are: 29″ x 28″

Image courtesy of: Art News, photographed by: Robert Bayer

Many of us know Piet Mondrian as a pioneer of abstract art and as founder of the De Stijl movement. The Dutch master is considered one of the 20th-century’s greatest and most influential artists. Mondrian’s signature style rarely veered past geometric figures in primary colors. Most common were the artist’s squares and rectangles in white, blue, red and yellow, and rigidly framed in straight black lines.

In celebration of the anniversary of Mondrian’s 150th birthday, Foundation Beyeler put together a beautiful exhibition showcasing his work. Titled “Mondrian Evolution,” the show presented the artist’s early formalist paintings besides his later abstractions. Courtesy of an article in Surface Magazine, the exhibition was “a format that finds overlap among painterly renditions of a forest at twilight, frenetic Cubist experiments, and minimalist canvases adorned with colored tape.”

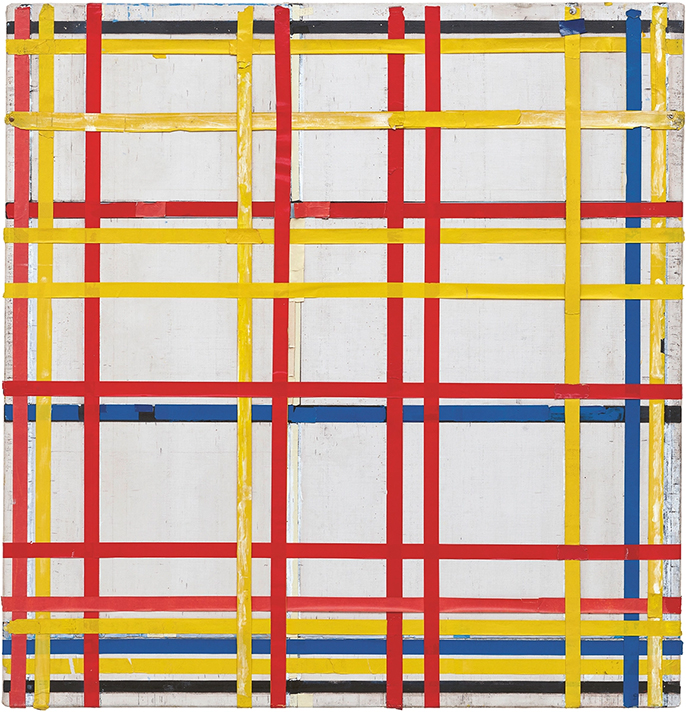

“New York City 1, 1941.” Oil and paper on canvas.

Dimensions are: 47″ x 45″

Image courtesy of: Art News, photographed by: Walter Klein

The show was curated by Ulf Küste; it draws upon Mondrian’s own thoughts regarding evolution as (courtesy of Art News), “the accumulation of experiences, on which a new phase of artistic development could build, in turn leading to further insights.”

Included in the exhibition are eighty nine paintings across nine galleries. The Foundation itself owns nine Mondrian paintings that span from 1912 to 1938; these served as the show’s core. A two-year-long Piet Mondrian Conservation Project ensued prior to the show. Specifically, conservation focused on four of the artist’s works owned by the Foundation. Luckily, La Prairie, the ultra-luxurious Swiss skincare brand, was 100% vested in sponsoring the paintings’ conservation efforts.

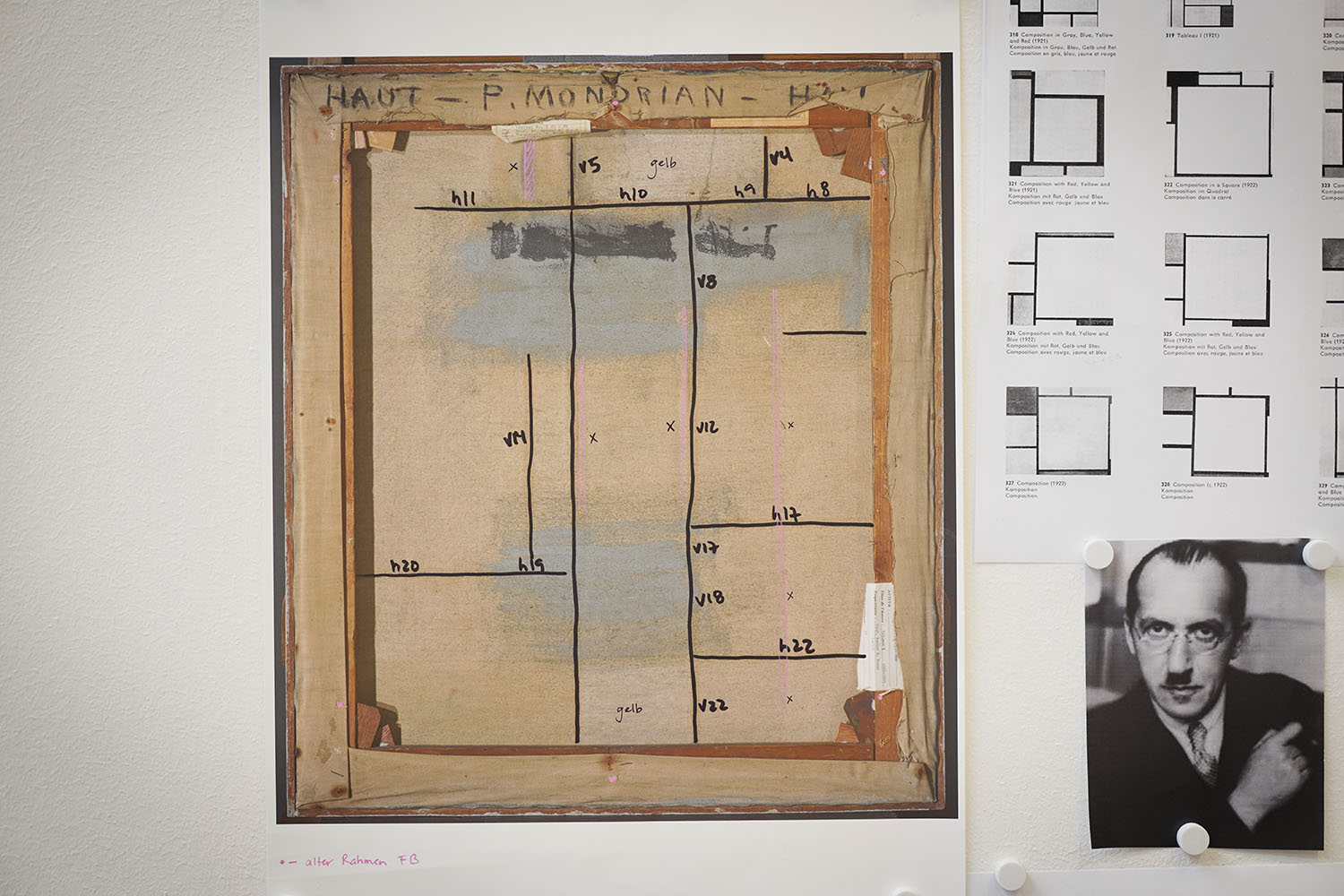

Markings discovered behind Mondrian’s paintings, courtesy of the project sponsored by La Prairie.

Image courtesy of: Cobo Social

The conservation efforts were led by Markus Gross, Fondation Beyeler’s head conservator. Gross notes that the artist was very private about his work, techniques, and processes. He was quoted as having said, “A line is not simply a line; a color field is not simply a color field. There is much more behind it.”

As such, it is not surprising that Mondrian was a perfectionist. Peeling back the layers of Mondrian’s paint, Gross and his team found evidence of wipes, scratches, and scrapes. This involved process pointed towards the conclusion that Mondrian viewed his paintings as a process evolving over time. Sections of the canvas were painted over again and again.

From left: “Lozenge Composition with Eight Lines and Red (Picture No. III), 1938, “Composition with Double Line and Blue, 1935, and “Tableau No. I,” 1921-1925.

Image courtesy of: In Exhibit, photographed by: Mark Niedermann

Specifically, “Tableau No. 1” was the perfect example of a piece with multiple revisions underneath. Made between 1920 and 1925, there is one specific zone with a uniformed charcoal grid underneath the paint. You can follow a matrix where Mondrian schematically veers from his grid in order to be “freer” in his artistry.

Using infrared technology and high-magnification machinery, the conservators uncovered black lines that have at least six layers of black and white paint… interestingly though, the white appears different than normal due to Mondrian’s brushwork’s direction.

All of these details are the result of a a long conservation project. Gross, who had previously conducted similar projects for the Foundation (for Max Ernst, Henri Mattise, and Alexander Calder) said, “We observe the artworks in our collection and document their condition constantly. We attached great importance to this process. Art is an important part of our lives. It testifies to how people see and understand the world, so it’s essential to preserve artifacts so we can remember, learn about, and honor those who were involved.” Particularly for Mondrian, these details point to an extremely deliberate process that explains why he became an even slower painter over time.

One of Mondrian’s early paintings… “Lighthouse at Westkapelle in Orange, Pink, Purple, and Blue,” 1910. Oil on canvas.

Dimensions are: 53″ x 30″

Image courtesy of Art News, photographed by: Den Haag

Our biggest takeaway is the parallels that can be drawn between Mondrian’s experience through monumental events such as World War I and recent worldwide events and the repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic. With everything that was happening around him, Mondrian never lost his focus.

Arriving in New York City, the artist was already quite established as an avant-garde painter. His relationships with some of the country’s most elite such as Peggy Guggenheim, Jason Pollock, and Lee Krasner were of great influence to Mondrian. In conclusion, we will quote Gross (as told to Surface Magazine), “Art is an important part of our lives. It testifies to how people see and understand the world, so it’s essential to preserve artifacts so we can remember, learn about, and honor those who were involved.”