Architectural Digest February 2002

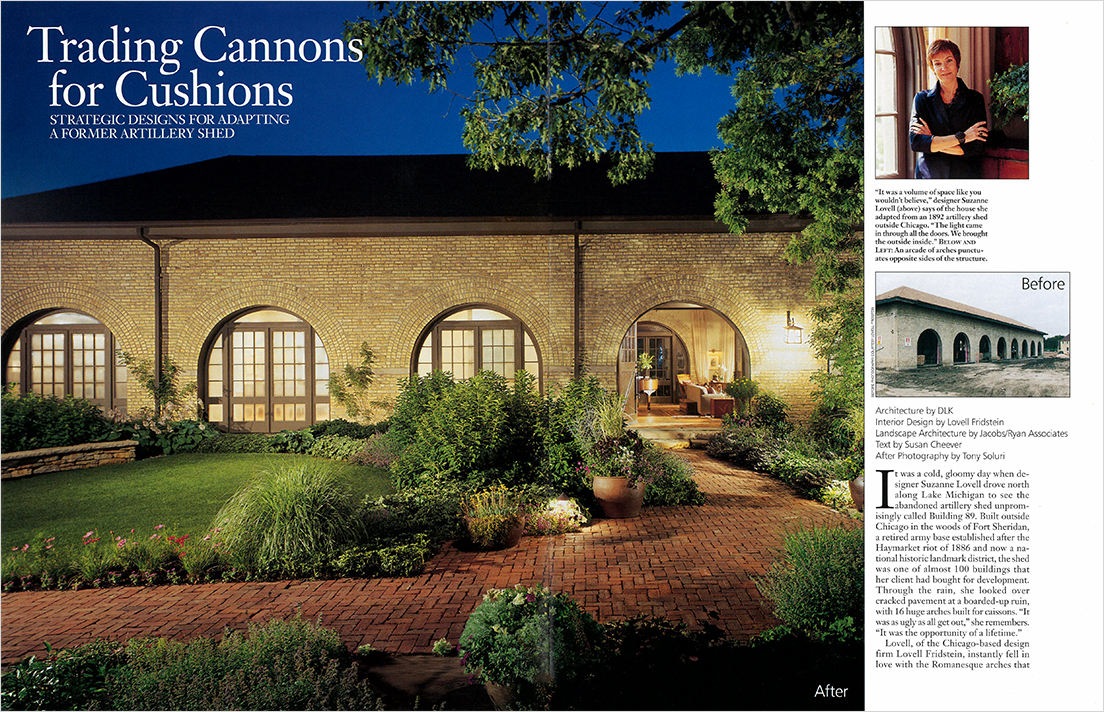

TRADING CANNONS FOR CUSHIONS

Strategic designs for adapting a former artillery shed

It was a cold, gloomy day when designer Suzanne Lovell drove north along Lake Michigan to see the abandoned artillery shed unpromisingly called Building 89. Built outside Chicago in the woods of Fort Sheridan, a retired army base established after the Haymarket riot of 1886 and now a national historic landmark district, the shed was one of almost 100 buildings that her client had bought for development. Through the rain, she looked over cracked pavement at a boarded-up ruin, with 16 huge arches built for caissons. “It was ugly as all get out,” she remembers. “It was the opportunity of a lifetime.”

Lovell, of the Chicago-based design firm Suzanne Lovell Inc., instantly fell in love with the Romanesque arches that march along the 135-foot-long building. “They’re the building’s real architecture,” she says. “Because they mirror each other, there’s a play of light back and forth. This building is about light.”

She worked with architect Howard Decker, formerly of DLK Architecture, to balance the character of the original space with the comforts of modern life. “It’s a new house contained within an old building,” says Decker. “You can see and touch the old walls. Adaptive reuse of historic structures is a balancing act. You try to find ways to give voice to a new life, while simultaneously preserving the old voices.”

Lovell agrees, “The most dangerous part of this project was the voluminous spaces,” she says. “It’s a huge space, but I wanted you to feel held.” To achieve this, she tucked the living room in the center of the 7,500-square-foot building and put the master suite at one end and the kitchen at the other. The floors were replaced with antique wide-plank hickory from Tennessee, and she added stairs that ascend from the living room to a bridge that crosses the space to the guest rooms. “I wanted everything to look as if it had always been there,” she says.

Each of the six rooms is dominated by the arches – to emphasize them, she ran a hand-forged iron drapery rod, hung with translucent linen curtains, down each side of the structure – and the house itself is dominated by the client’s passions. A trained gourmet cook, he needed a large kitchen as well as a wine cellar and humidor, and a place for his fly-fishing gear. He also needed space to display his many collections, including etchings with which Frank Lloyd Wright’s widow paid her legal bills to his father’s firm. “The challenge was to take these gargantuan rooms and make them warm and livable,” the client says.

The overwhelming scale of Building 89 seemed to call for simple lines and tactile finishes of Asian antiques: a monk’s table from Thailand, a Chinese altar table and demilune tables from China’s Shanxi province to echo the arches. “The architecture is so strong and the materials are so strong, the Asian pieces bring a personality of ancientness, a soulfulness that tames down that strength,” Lovell explains.

In the living room, a 26-foot-high ceiling holds an antique wrought-iron chandelier, which lights the brick-and-limestone fireplace with corner pieces salvaged from the exterior tie rods. Above it, an oil by Chicago painter David Klamen looks down on the monk’s table and the alter table arranged with a sofa and chairs on a Chinese sea-grass rug. A yellow Alexander Calder stabile sits on a red-lacquered Chinese shoe box, and on the mantelpiece, an etching from the Wright collection leans next to a pair of Japanese candlesticks. Two rice baskets flank a Joan Miró watercolor on a Japanese chest under the staircase, where the railings frame Sally Chandler’s Sunflower Diptych. The master bedroom is a sanctuary with a view of the Fort Sheridan water tower, modeled after the campanile in Venice’s Piazza San Marco. The bed sits under a Joseph Piccillo mixed-media piece, next to a James Whistler etching from the Wright collection and a Bill Mauldin drawing, signed to the client from the cartoonist. A black-lacquered Chinese money chest gleams at the end of the bed; by one arch a bamboo moon-gazing chair is pulled up to a demilune table. Under the windows, two wing chairs and an ottoman surround a table draped in matching toile.

The south end of the house is an open kitchen, with shelving for cookbooks and a table with mahogany Thonet chairs. “I love to cook,” says the client. “I’ll grill Chilean sea bass or whatever’s good in the stores. I cook, we sit around, and everyone’s helping. It’s fun – sometimes everyone cooks a dish.” Lovell provided him with an Irish butcher block, Italian green-and-white-marble counters and sink, and top-of-the-line appliances. Between the kitchen and living room, she installed one of the shed’s original doors as a backdrop for a Ming-style Chinese painting table, topped with ceramic teapots. The formal dining room’s 18-foot ceiling is anchored by a pair of Tibetan juniper-wood temple chests. Oversize mirrors bring the outside in through the room’s two arches, and Lovell added a darker color to the walls just below chair rail height. “I wanted to create a subtle consistency with the arches and with colors,” she says.

Between the arches on the west wall, a pair of Indonesian plantation chairs are pulled up to a Chinese bamboo-and-elmwood table. Outside the arches, landscape architect Bernard Jacobs, of the firm Jacobs/Ryan, created a transition to the garden with outdoor living and dining areas. The shed’s original doors serve as a backdrop, and a trellis, made of barn beams from Wisconsin and red-cedar logs, shades the space. The building’s floor bricks – made from the fort’s own clay – were used to create walkways between the living spaces and the gardens. Across one walkway, a sculpted horse trough, now functioning as a fountain, is surrounded by birch trees and 50 varieties of perennials. “We used materials found in the fort – brick and bluestone,” Jacobs says. “Each room and each window faces its own garden.”

The client finds living in a former artillery shed uncannily peaceful. “I wake up in the morning, and the sun is shining in from the east through the arched portals, and it’s glorious,” he says. “The birds are singing. It’s like being at home in the woods. There’s a lot of stuff made by God in this house and not a lot of manufactured stuff. There will never be another house like this.”

Text by Susan Cheever

After photography by Tony Soluri