Financial Times How to Spend It September 2015

BRINGING ART TO LIFE

By Emma Crichton-Miller

Last October, at Frieze Masters, the art fair for Old and Modern Master artworks, located in a vast white marquee at the other end of Regent’s Park from Frieze itself, one exhibition stand stood out. In between decorous cubicles where world-renowned galleries offered masterpieces under careful lighting, against walls painted contrasting shades of grey, London-based dealer Helly Nahmad had created chaos. In four small rooms, exposed in the round like a stage set and crammed with 1960s furniture and teetering piles of art magazines, shockingly valuable paintings by Picasso, Miró, Jean Dubuffet, Giorgio Morandi, Lucio Fontana and Max Ernst, sculptures by Giacometti and other modern masterpieces jostled for attention with old-fashioned radios, encrusted ashtrays, towers of books, socialist posters and bundled issues of Paris Match. Meanwhile, antiquated black and white television monitors ran clips from the Winter Olympics, news footage of the Paris riots and old Godard movies. The work of music video production designer Robin Brown, commissioned by Nahmad to create the imagined Parisian apartment of the fictional Corrado N, or “The Collector”, it proved a magnet for visitors.

For some, the display was a poignant exercise in nostalgia – one dealer was heard remarking that he still knows collectors like this. For others, however, it was a startling reminder of how differently most art collectors choose to live with their treasures. Today, it is the minimalist aesthetics of Annabelle Selldorf, the suave design intelligence behind the Frieze Masters marquee, that governs. Where major works of modern and contemporary art can now cost many millions, and even Old Masters can set you back a substantial amount, serious collectors are generally not just in the position to buy the art but, increasingly, to commission its home too. Moreover, the past 40 years have seen a tremendous boom in ambitious museum building throughout North America and Europe. These extraordinary buildings – from Louis Kahn’s magisterial Kimbell Art Museum and Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim in Bilbao, to Zaha Hadid’s Maxxi: Museum of XXI Century Arts in Rome and Renzo Piano’s latest creation, the new Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan – have raised the bar for imagining the kind of spaces that might best serve the artworks they house.

Living with works of art, however, is very different from visiting them in a museum. An architect or interior designer is required not just to honour and guard the artwork, but also to ensure that it is fully integrated into the domestic life of the collector – whether that involves entertaining on a grand scale, small children or inquisitive cats. Where a museum acts as a mute and neutral backdrop, a domestic interior should express the characters of the collectors and reflect their own feelings about their artworks.

Contemporary architects are not the first to have explored this territory. You have only to think of William Kent in the 18th century designing Houghton Hall to house Robert Walpole, his family and his art collection (with equal importance given to each), or Jeffry Wyatville building the 6th Duke of Devonshire a sculpture gallery in Chatsworth House, a hundred years later.

One of the stars in the field today, is Seattle‑based architect Jim Olson, owner and founding principal of Olson Kundig Architects. Imagining he would be an artist as a boy, but growing up to be an architect, Olson says that art was “woven into the architecture” from the beginning. It was not just a matter of the artistry of the architecture, but also having a feeling for “the importance of art to my clients”. In the early 1980s Olson began to collaborate with artists on various projects, including James Turrell, and then worked as the local architect on Robert Venturi’s Seattle Art Museum. He was then commissioned by the major art collectors Richard and Betty Hedreen to build his first “art house” in Seattle. His inspiration, he explains, was Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum, with its distinctive sequence of pure vaulted gallery spaces. “And so this house too was along a spine,” Olson explains, with alcoves either side for sitting rooms, the gallery or hallway broken up to create a series of separate display walls, one for each artwork. “One thing that bothers me about museums is that you will be looking at one piece but be distracted by others out of the corner of your eye. This strategy helps you to focus on one work at a time.” As he admits, “That experience led to every other art collectors’ house I’ve done.” He talks like an artist: “You want to create a mood with the art, use the art theatrically to define the personality of the space.” At the same time, scale, mood and materials are different every time, with the character of the collector and his or her collection at the core of the design. “These collectors are passionately in love with their art – it’s part of their family almost – so the house must bring them together carefully and precisely.”

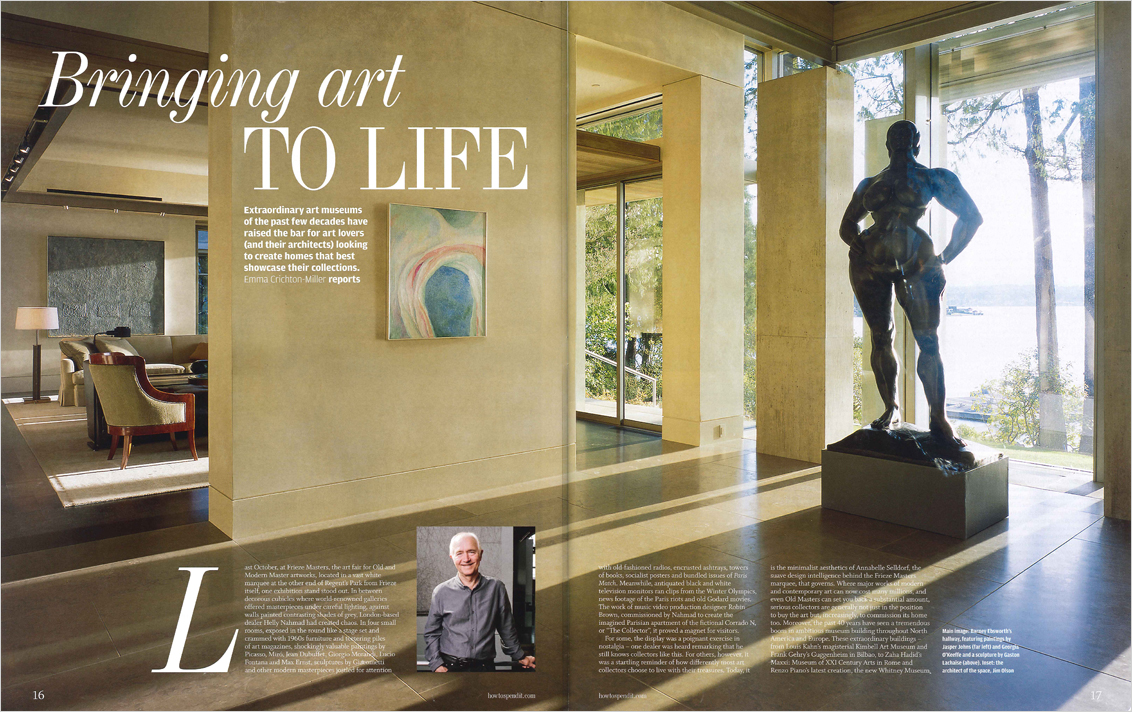

Later, Olson was commissioned by Barney Ebsworth, travel entrepreneur and a committed collector of 20th-century American art (he has significant works by Georgia O’Keeffe, Edward Hopper, Jackson Pollock and Jasper Johns, among others) to create a home on the lake in Seattle. “He wanted a house that was a little low-key and related very much to nature.” Olson chose a soft palette of colours, inspired by the rocks, tree trunks and grey skies of Washington state for both the exterior and the interior. For the latter, he also created a large hallway marked by columns, with a very strong black and white painting by Franz Kline at one end and one by Marsden Hartley at the other. The idea was to place four large-scale works in the alcoves between pillars. Smaller-scale works, or those with a horizontal format, such as Ebsworth’s magnificent life-sized double portrait Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott (1969) by David Hockney, are placed in the dining and drawing rooms, with their lower ceiling heights, off to the sides. The ratio of these heights, Olson tells me, is based on the divine proportion beloved of Renaissance artists and architects. A special place was chosen for Ebsworth’s favourite work by Edward Hopper, Chop Suey (1929). “It’s in my den,” he explains. Ebsworth had come to Olson with a floor plan and some ideas about where to put the art. “The spaces turned out to be exactly right,” he says. His only disagreement with Olson was that he refused to put any art in the body of the hall. “I will never hang anything in that hallway. It is Jim’s artwork.”

If Ebsworth’s collection is largely painting, in Denver, Olson has designed both the Kirkland Museum of Fine and Decorative Arts and a private house for Merle Chambers and Hugh Grant, owners of one of the best collections of 20th-century decorative arts in the United States. Their fine art collection includes paintings by Matisse, Vance Kirkland and Matta, as well as sculpture by Alexander Calder and Barry Flanagan, while they also own furniture by Christopher Dresser, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and modernists Frank Lloyd Wright, Finn Juhl and Josef Hoffmann. The challenge was to show small and large objects in the same monumental space – and protect them from the cat. So Olson created spaces specifically for the large canvases and the Matisse and he designed a series of simple glass cabinets for the decorative-art objets – light streams freely from the windows onto the international ceramics, glass and silver. Other objects are placed in alcoves in the grand gallery hallway, alongside a few more fragile pieces of furniture on plinths. “You don’t just see the object, you think of it as correctly placed, as if you had said to the object, you are special,” says Chambers. “Jim does that for things.” Chambers particularly admires the division of the house into a more public side, and then a family side, with ceilings lowered to create intimacy. At her request, the staircase to the upper floors is hidden behind a panel ”so the upstairs is very private“.

Further east, in that great architectural city Chicago, Suzanne Lovell trained as an architect and today specialises in the intersection of fine art, architecture and interior design. Often required to contribute to the design of a building, her team’s area of expertise is in ensuring that every interior detail – soft furnishings, furniture, lighting – serves to enhance the collectors’ relationship with their collection. Lovell will also source fine artworks to complement a collection if required. She has had projects all over the United States, from apartments on the Magnificent Mile in Chicago to pieds-à-terre in New York City, from a beach-front house in California to Florida penthouses. One client, Dr JoAnn Eisenberg, lives in a rare, historically listed house in Chicago dating from 1866. Nine years ago, she and her husband decided to renovate it for the second time. Enthusiastic collectors of art deco furniture, rare books and Hungarian photography, they had also been accumulating Native American artefacts – textiles, ceramic vessels – for nearly 30 years. This collection had never been on display in this, their main home, and instead had been split between storage, various museum exhibitions and their other homes. Lovell immediately saw its potential: “We were struggling to create an entrance foyer in a narrow house, so we created a 16ft-long cabinet of goatskin and bronze with spaces for the Native American items. And we displayed a large portion of the Edward Curtis photographs in the powder room. This brought the house alive.” Dr Eisenberg adds, “Suzanne showed us how to live with our Native American things and our art deco pieces. She made it coherent.” Lovell used a soft palette of colours and menu of textures to create warmth throughout the home, while little details – the horizontal graining of the carpentry echoing the horizontal weaving of the Native American textiles – draw attention back to the art. “The whole project was so intellectually stimulating; I learnt to look at each object as an individual work of art, not just part of our collection,” says Eisenberg.

She and Lovell were constrained a little by the planning laws for “landmark” buildings in the United States. Imagine what it was like therefore for architect Thomas Croft, invited to renovate an apartment for international art dealer Per Skarstedt in London’s prestigious Albany. Skarstedt travels constantly and has multiple homes in Europe and the United States. His new Long Island home has just been designed by Annabelle Selldorf. Everywhere he lives, he places works of art by his favourite 20th- and 21st-century artists – Martin Kippenberger, George Condo, Georg Baselitz, Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince – alongside midcentury-modern furniture. Croft was aware that given planning restrictions, his would need to be a job “editing spaces to facilitate the display of art”. His interventions have been discreet so far: hiding speakers behind walls, painting the walls and woodwork white, inviting interior designer Sarah Delaney to add the subtly sumptuous curtains and carpets that give the drawing room its luxurious softness. Here, Skarstedt has taken great pleasure in displaying his George Nakashima table, his George Condo and Martin Kippenberger paintings and his Rebecca Warren sculpture. “The art needs to feel like it is his, and he needs to feel at home,” says Croft.

Seth Stein is another London architect, expert in adjusting listed period houses to accommodate contemporary art collections. For one London family, “literally the fabric of the house is the artwork,” he says. Stein had to build into his design a colourful Richard Woods staircase, a work by sculptor Cornelia Parker (Twenty Pieces of Silver), which hangs on invisible lines close to the floor, and a white “flotsam and jetsam” chandelier by Stuart Haygarth, among other pieces. The client says of the project, “I think our priorities were less about the collection than about creating a warm and welcoming home for us and our friends.” Flexibility of space was also a priority. At the same time, they thought carefully about lighting and colour. “Context is everything in terms of understanding a work of art – the pieces are different from the way they were before,“ she says.

Maria Sukkar, a Lebanese collector also based in a classic Victorian London townhouse, has different priorities. “At this point we live for and around our collection. We are prepared to sacrifice seating space for the art. The art is everywhere – on the floor, on the walls, hanging from the cornices and in the cloakroom.” Sukkar has worked with architect Rabih Hage to accommodate large-scale works by Jenny Saville, Berlinde de Bruyckere and Paul McCarthy, alongside works by Louise Bourgeois, Cindy Sherman and Akram Zaatari. One work, a chair by Sarah Lucas, came with a roll of wallpaper, which they used to repaper a corner of the room. “We needed Rabih to maximise space in an elegant way,” Sukkar explains, citing the clever play of colours in the furniture, the custom-made elongated chandelier in the dining room, and the art-friendly, light-grey walls. Hage also helped increase the natural lighting by installing stylish double-glass doors by artist-designer Christophe Côme between two reception rooms. ”The light is low-key,” Sukkar says. “This is not an art gallery.” For in the end, as Hage said to me, “You must not be too precious about the art. These are above all homes and the art must bow to the overall atmosphere and personality of the collectors.” Mischievously, given the elegant homes he has helped create, he even confesses to a sneaking admiration for Corrado N.