Gulfshore Life Home January 2025

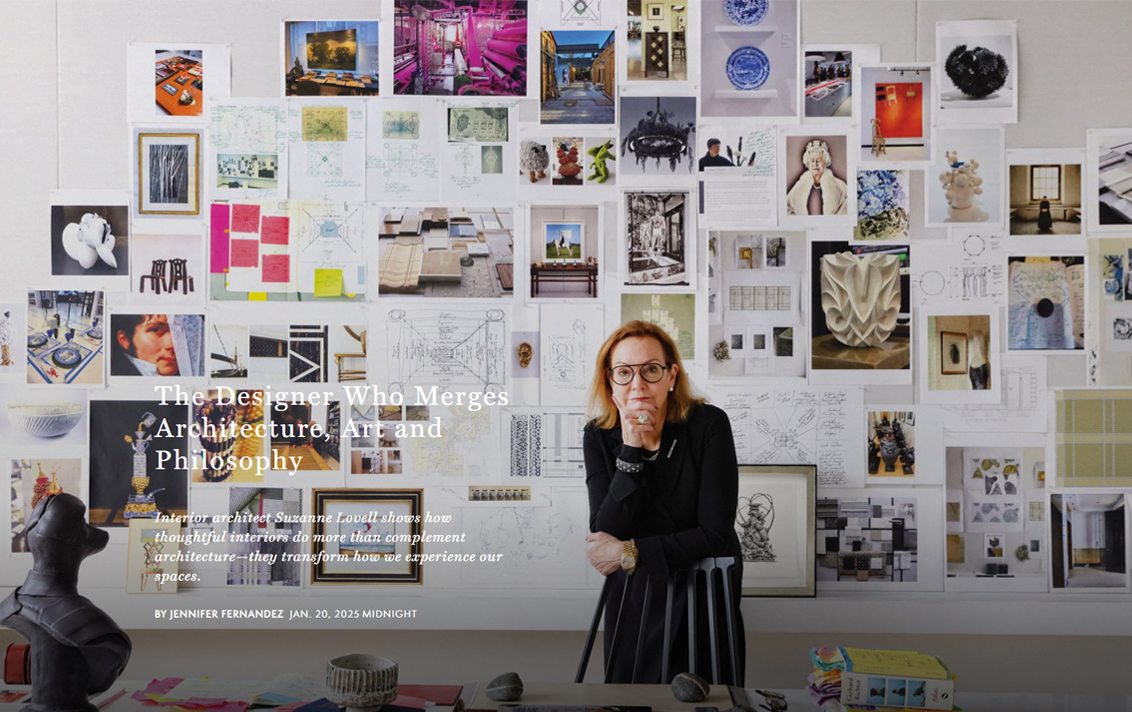

The Designer Who Merges Architecture, Art and Philosophy

Interior architect Suzanne Lovell shows how thoughtful interiors do more than complement architecture – they transform how we experience our spaces.

Standing in Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s Chicago office early in her career, Suzanne Lovell noticed a disconnect. Her colleagues—brilliant architects who could fully articulate a building’s geometry—often missed the intimate details that make a space sing: the precise curve of a Chippendale chair back, the tactile pleasure of a brass door handle, the way a paint color appears as natural light plays across walls at different hours of the day.

But, from the outset, Lovell was primed to see interiors differently. As the daughter of an accomplished American decorative arts historian, the Chicago designer with a strong Naples following grew up immersed in the elements that elevate a room from functional to transcendent. Studying architecture at Virginia Tech added technical rigor to her foundation, while her minor in psychology aided her understanding of how people experience spaces. A philosophy began to unfold. “Interior design is applicative; interior architecture is woven,” says Lovell, who founded her firm in 1985.

This observation became her calling card. Her idea—that thoughtfully conceived interiors don’t just complement architecture but fundamentally enhance it—has positioned her at the vanguard of interior architecture, a discipline that’s gained traction among designers over the past decade but remains largely unexplored by traditional architects. She takes the concept further, looking at functionality and aesthetics—along with engineering, construction and psychology. “You have to be facile in all those areas, or you can’t do what we do,” she says.

When crafting a space, Lovell starts with holistic problem-solving: Remove unnecessary columns for better flow; pair existing wall panels with wide-board shiplap to unify the old and new; paint water-facing window frames black instead of the usual white, allowing them to disappear into the horizon at night when the space is most used. Along the way, Lovell—whose firm includes an art consulting arm—is mapping out the art. “That’s what finishes a home,” she says. She also draws on her deep bench of craftspeople to develop site-specific surfaces, furnishings and finishes. The designer envisions vignettes as chapters in a story. “Somebody is going to stop, stand, read the room and look at a piece,” she says. “You’re going to see this piece first, this piece next.”

Her approach drove the dean of Virginia Tech’s Myers-Lawson School of Construction to invite Lovell to participate in the first practice-based doctorate program for environmental design philosophy in 2021. Unorthodox as a return to school might have been for someone so established in her field; for Lovell, it was second nature. She is, after all, the quintessential student—a voracious reader (with an annotated library full of sticky-noted books to prove it) and a perpetual knowledge seeker. “I eat, sleep and drink interior architecture,” she says with a laugh. “I think that’s my love for the PhD program—I get to do the busman’s holiday all weekend long.”

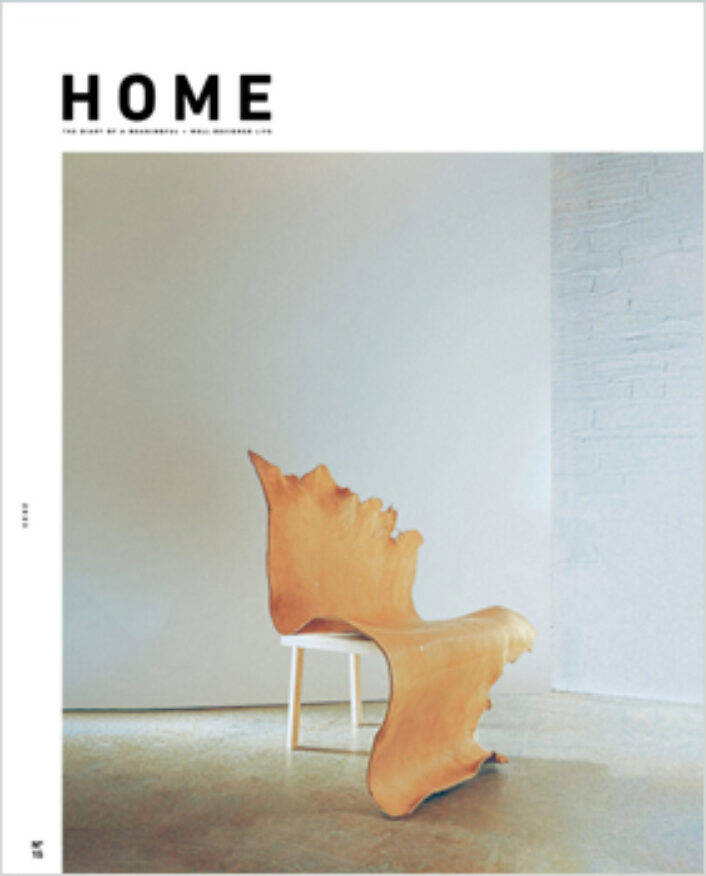

Her dissertation, which she calls “It’s Not About the Chair,” explores how interior elements and fine art rise to architectural significance through a series of material studies encased in clear boxes. The name reflects her work’s wall-tearing, surface-conceiving aspects and cheekily responds to the decades she’s spent explaining and sometimes justifying her craft. “There was a time when I had to call myself a decorator so people could understand I wanted to do the interior,” she reflects wryly.

Set up exhibition-style in her office, the four vignettes tell different stories: One of them sets a Christian Astuguevieille Moiste chair with coiled rope and thread samples in desert and metallic hues, suggesting a dialogue between organic and structured elements. Another one pairs a Matthew Shlian paper sculpture next to Ai Weiwei’s book Humanity and textural black and gold panels—a nod to how mathematical thinking and human expression intersect to create meaning in a space. The boxes highlight the creatives she collaborates with while revealing how different personalities can be interpreted through the same integrated approach.

For her, design is a perpetual learning endeavor—Lovell’s constantly cataloging sources that span styles, eras and provenance, as well as blending collaborators’ and her own thoughts to expand her creative language. Much of what Lovell practices is an act of world-building. Instead of working off an existing product (a chair for a seating arrangement, wallpaper for a dining room), she creates something from nothing. The space weaver collaborates with artisans on original commissions, relying on instinct, history, and her vast knowledge and appreciation for craftsmanship.

For a Naples home in an amoeba-shaped building, where the clients worried about sand-scratching hardwood floors, Lovell collaborated with the same installers behind Miami International Airport’s terrazzo flooring to create a richly patterned surface resembling the home’s rugs. Careful calibration was required for the scale and placement of each pattern. For another Naples condo, she hired Tennessee woodworker Caleb Woodard to carve hulking, 10-foot doors that feel more like sculptures than utilitarian fixtures.

“It’s a layered opportunity,” Lovell reasons, explaining that a sense of wonder also drives her creative impulses. “I have a Rolodex in my head, images of many different crafts and craftspeople, and it’s just an imaginative thing: ‘What if we had a wonderful carved-wood door—would Caleb Woodard do that?’ I’m a maker, so I understand the enthusiasm when someone comes and says, ‘Can you do this?’ You bet I can!”

Through her PhD studies, Lovell sought to distill her practice—and the very origins of creativity. “There’s a lot of philosophical discussion about creativity and the why and the how,” she says of her classes. She found particular resonance in French philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s concept of ‘reverie’—the conscious daydream state where creativity flourishes. In his writings, Bachelard described this as the moment when imagination is active and aware, allowing the creator to freely explore possibilities while drawing on memory and experience. “He’s talking about words, but I’m utilizing the same reverie around a material palette,” she says.

Still, Lovell is quick to add that her work is less a reflection of her worldview and more a result of the dialogue with her clients—she is merely the vessel. “It all comes down to trust,” she says. “I’m

trying to get them to go through my sieve, but I’m also going through theirs.” The result? Spaces that feel like fingerprints—uniquely matched to the client’s vision while enhancing the architectural story.

From understanding how materials will perform in coastal environments to anticipating how spaces will feel at different times of day, every design choice builds toward the larger narrative. “The floor, the walls, the light, the drapery—that’s all architecture,” she says. “My joy is developing a storyline.”

By Jennifer Fernandez