The first monograph devoted to Ingrid Donat

Éditions Norma/Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Excerpt from Ingrid Donat, Creation without Limits by Anne Bony

FIGURES

page 17

The exhibition was a huge success. Encouraged, Ingrid Donat continued her artistic mutation and launched herself into figurative and allusive creation. A series of themes then cadenced a sustained work period that was marked first of all by the beauty of the nature that prompted it. The bay windows of her large house in Villennes-sur-Seine provide a view of the garden’s receding perspective, studded with magnificent trees. The gingko biloba inspired a collection of Gingko bronze lighting fixtures and candlesticks (1997) that seem to bend in the wind. The bronze weds the tree’s bark, the characteristic leaf gives rhythm to the movement.

The artist was fascinated by primary arts and the singular representation of animal nature. She discovered its force and overt beauty at an exhibition. “In New York, modern works were set side by side with primitive art, for example, Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was hung next to totems.” This unexpected revelation gave birth to the Girafe floor lamps and candlesticks (1998), whose stems are delicately edged with reliefs that are both random and rhythmic. In the same way, irregularities on the envelope of the commode are softened by the bronze.

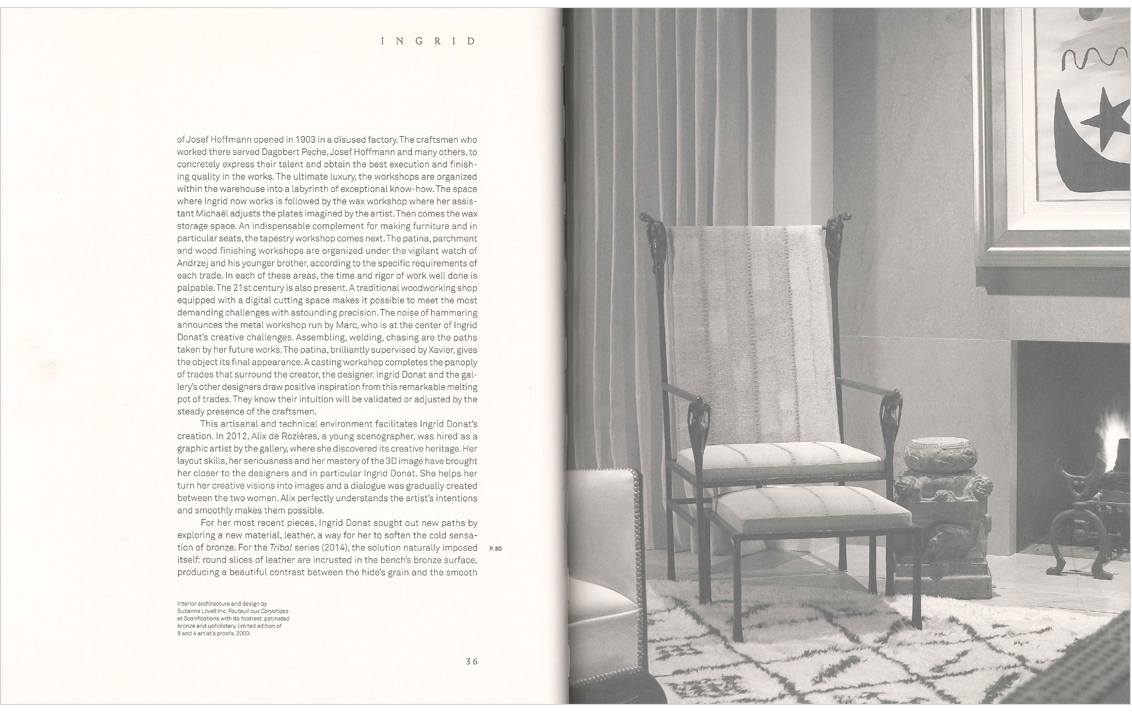

The theme of the Caryatides then imposed itself. These are figures of young women who support an entablature, as on the Erechtheion on the Acropolis, replacing a column, pillar or pilaster. Sculpture henceforth had a function for her. Here, she delivered sculpted uprights of women with lowered heads that decorate and structure a collection of furniture comprised of a daybed, a banquette, a bench, a bench with armrests, a bench-bookcase, a chair, an armchair, a coiffeuse and its seat, a stand, a lady’s desk, a man’s desk, a small table and a large console table. This series of sculpted furniture, the Caryatides, whose first models date from 1998, were, as always, made with the support of the foundry. Didier Landowski recalls their long collaboration: “Starting in 1998, I exhibited Ingrid’s objects and furniture at the foundry. That shows how much I liked them! The first problems were mechanical, material resistance for the chaise lounge, fragility of the legs for the chairs… But this was nothing compared to the problems to come.” Assembling this furniture was complicated, remembers Nicolas Gay, the chaser: “The texture had to be coordinated on the entire piece.” For the uprights of the furniture, she designed motifs evoking scarification with signs slashing the surface of the bronze. “I couldn’t get away from that, I needed to create something on the material, hence these motifs… I liked the effect.” To eliminate the intermediaries, she sculpted the plate herself, to remove the smooth appearance. This remarkable collection permitted her to apply the refined principles of Art Deco using sheathing made of parchment, a natural material rich in subtle hues and reliefs on the wood panels of the coiffeuse and desks. The seats are stretched with a painted and tied fabric that she made herself. She was inspired by old African fabrics that she saw at the flea market. She used the principle on a linen canvas whose threads she removed, which she then dipped in red and created a relief by tying on the thick fabric. It was difficult and time-consuming to handle, but she liked the effect. The Caryatides ensemble was exhibited in 2000 with the title “Muebles et sculptures: at the Cazeau-Béraudière gallery in Paris. It was with this gallery that she took part in the first session of the Arts and Design Pavilion.

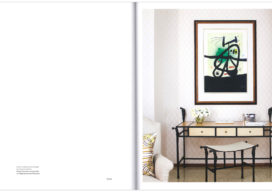

Primitive art fascinated her. She thought of it as a way to take hold of the material without any prior ideas, to celebrate a folk art, an art that was as naïve as it was ceremonial. For her new series, the Scarifications (2000), she added traces on the panels, whereas the architecture of the furniture was sober, and mixed tropical wood with bronze. In the African tradition, scarifications are divided into two quite distinct categories; some are in intaglio, others in relief. The former can form short thin lines, more or less dense, more or less stretched out, isolated or grouped into parallel lines, and sometimes forming rather complicated groups, in the Hausa of Nigeria, for example. In others, these grooves are very stretched out, long and thin, as in the Teke people who live in the two Congos, whose fetish statues faithfully reproduce these lines. In other groups, the scar is much wider and more or less long. This practice is particularly widespread in West Africa. The Bariba, Bambar and Mossi offer beautiful examples of it. Scarification in relief produces genuine graphic groups with unquestionable composition and execution qualities, as in the Bamileke of Cameroon. Archeological research has shown that this technique dates back centuries; its fascination is timeless. Ingrid’s artistic composition is very naturally in line with this tradition of work on the skin, on the surface of the furniture, a composition clearly served by the use of bronze.

Her Buffet aux Femmes Girafes is an example of the juxtaposition of bronze, which forms the structure of the sculpted piece of furniture, and the scarified and patinated fabric that evokes leather and sheathes the storage elements. In her Commode aux Femmes Girafes the motif sculpted in the paper is reproduced for an all-bronze piece of furniture with, for the first time, a treatment of the exterior element on the entire surface. An original translation of the skin of the piece of furniture is sensed with a subtle vertical pigmentation. The piece calls on the senses, and in particular sight and touch. The influence of African art remained implicit in her creation, notably with the floor lamps Femme Africaine, Homme Africaine (2004).

BIOGRAPHY OF INGRID DONAT

courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Ingrid Donat creates sculpted furniture, most often in bronze. Taking a painterly approach to this weighty medium, Donat draws on diverse decorative influences. Art Deco, tribal tattooing, the work of Gustav Klimt and Armand-Albert Rateau have all inspired the intricate patterning of her work.

Elements of Donat’s practice remain consistent. Her creative process begins with a sheet of wax, which she inscribes, carves and shapes to form the ‘skin’ of her work. This structure is then applied to her designs. She herself engraves the bronzes, paints the upholstery and treats the wood. Her pieces have been cast at the same bronze foundry, the Blanchet-Landowski, for over 20 years, as the stamp they bear goes to prove.

Though often large and heavy, there is a delicacy to Donat’s work. Almost like armour, she uses bronze to shield an idea of the fragile.

In addition to her skilled craft, Donat is also an accomplished engineer. Commode 7 Engrenages incorporates a column of cogs into its sides. They begin to whir when the chest’s drawers are opened or closed. The intrinsic mechanism animates the piece with movement and sound.

Born in Paris into a family of artists, Donat was brought up in Sweden. In 1975 she returned to her birthplace to realise her passion for sculpture at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. During these years she began to apply her sculptural talent to functional pieces, strongly encouraged by her mentor Diego Giacometti. Only in 1998 did Donat begin to exhibit publicly a body of work she had been creating for over twenty years.