Fine Art

A thank you to Jo van Gogh- Bonger

Johanna van Gogh-Bonger sits in her living room, circa 1909. On her walls are Henri Fantin-Latour’s “Flowers” and van Gogh’s “Vase of Honesty,” 1884.

Image courtesy of: The Sydney Morning Herald

The art world owes a big thank you to Johanna van Gogh-Bonger. It is thanks to the artist’s sister-in-law that he was presented to the world and set up for success. The astute woman was raised in a middle-class family and set off to work as an English teacher in Amsterdam. Soon after meeting her, Theo, Vincent’s younger brother, began pursuing the young teacher even though she was dating someone, and eventually she relented. Drawn to culture and wanting to be around artists and intellectuals… Jo quickly realized that this was something Theo could provide her with.

In 1888, the pair married and a new world opened for Jo van Gogh-Bonger. In Paris, Theo was at the forefront of art dealing; he represented young artists who went against “the stony realism imposed by the Academy des Beaux-Arts. This was an amazing and instant niche for Theo since other dealers were not interested in working with the Impressionists. This group included the likes of Gauguin and Picasso; but in this group were Theo’s clients and personal heroes.

“Johanna Bonger,” painted by her second husband, the Dutch painter Johan Cohen Gosschalk, 1905.

Image courtesy of: Wikipedia

Jo and Theo’s apartment was filled with Vincent’s canvases. Crates arrived weekly with the new paintings that Vincent “churned out.” At this point in time, Vincent’s paintings were filled with olive trees, yellow suns, and peasants working in the Provencal sun. His hope was that Theo would be able to find buyers for his paintings. As more and more paintings arrived, Jo began to receive an “education” in modern art.

In the midst of this frenzied painting spree, Theo recognized that Vincent’s mental state was quickly deteriorating. The artist stopped bathing, his teeth began to rot, and he famously cut off his ear following an argument with his roommate, Gauguin. When a different style of painting began to arrive, Theo realized that he was seeing something innovative. About the night’s sky of Arles that Vincent painted, he said (courtesy of The New York Times), “In the blue depth the stars were sparkling, greenish, yellow, white, pink, more brilliant, more emeralds, lapis lazuli, rubies, sapphires.” “The Starry Night” was an example of Vincent searching for something deeper… as much as Theo appreciated this revolutionary style of painting, he realized that his clients would not yet understand this new manner. Sadly, within a short period of time, both Vincent and Theo died leaving Jo with roughly 400 paintings and several hundred of Vincent’s drawings.

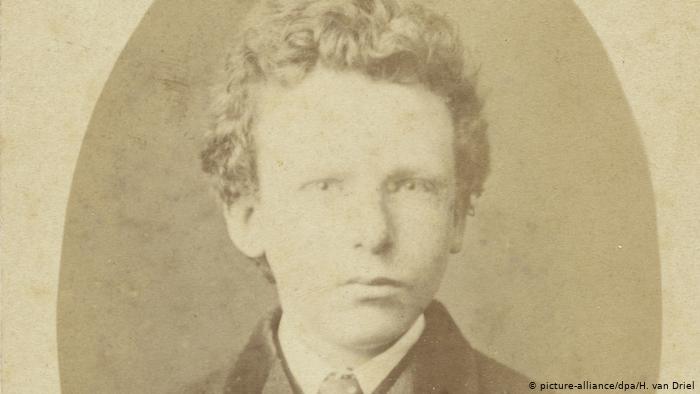

The only known photograph of Theo van Gogh aged 19.

Image courtesy of: DW

All alone, Jo took a friend’s advice to open a boardinghouse in order to generate some income. Rather than leaving all of Vincent’s paintings in Paris as Emile Bernard suggested, Jo decided to keep all of the paintings with her. Soon, virtually every inch of wall-space was filled with Vincent’s paintings. She wrote that Theo gave her two distinct responsibilities, “As well as the child, he has left me another task- Vincent’s work- getting it seen and appreciated as much as possible.” The widow spent a lot of time researching the art market in order to get a better understanding of her task at hand.

Jo realized that pairing Vincent’s letters in conjunction with his artwork would help people to better appreciate his work. The letters helped showcase that Vincent wanted to make art for the “average person” rather than for the upper class as is evident from this quote, “No result of my work would be more agreeable to me than that ordinary working men should hang such prints in their room or workplace.”

Vincent’s paintings at an exhibition in Antwerp, Belgium in 1914.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times Magazine

As Jo began to pair Vincent’s art with his personal life the public began to appreciate his paintings. Jo had managed to fuse the art with the artist. The sister-in-law gradually convinced clients to look at Vincent’s work and his life as one collaborated thing rather than two separate entities.

In 1905, Jo arranged a major exhibition in order to present a big statement about Vincent’s work. Rather than delegating the show’s details to someone else, she did everything herself. On her own, the virgin dealer rented galleries, printed advertisement posters, and invited influential persons. This exhibition, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam was and remains the largest of van Gogh’s to date at 484 works on display.

Correspondence between Theo and Vincent van Gogh from 1885. A sketch of “The Potato Eaters” is drawn.

Image courtesy of: Widewalls

In essense, Jo learned as she went along… she was self-taught in her approach to marketing her brilliant and prolific brother-in-law. Emilie Gordenker, a Duch-American art historian who took over the Van Gogh Museum last year said, “She had to make it up as she went along. She didn’t have any background in this. But she was forthright and direct and at the same tine very unsure of herself. That turns out to be a very productive combination of traits.”

For the remainder of her life, Jo was committed to honoring her husband’s wish… for his artistically gifted brother to become known to audiences throughout the world. She continued to believe that van Gogh’s letters (especially the ones between the brothers) were the key to understanding Vincent and in such, his art. Among her final self-imposed tasks was to publish the letters in English. Jo’s belief in both Theo’s passion and Vincent’s genius are her everlasting gift to us all. Thank you Jo!