Architecture

NYC’s new David Geffen Hall

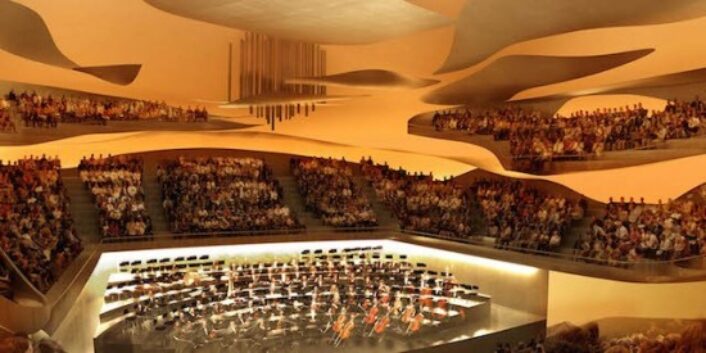

Parts of the original building were rearranged during the renovation. Most critical, an open floor plan was created which doubled the square footage on the ground level.

Image courtesy of: Architectural Digest, photographed by: Michael Moran

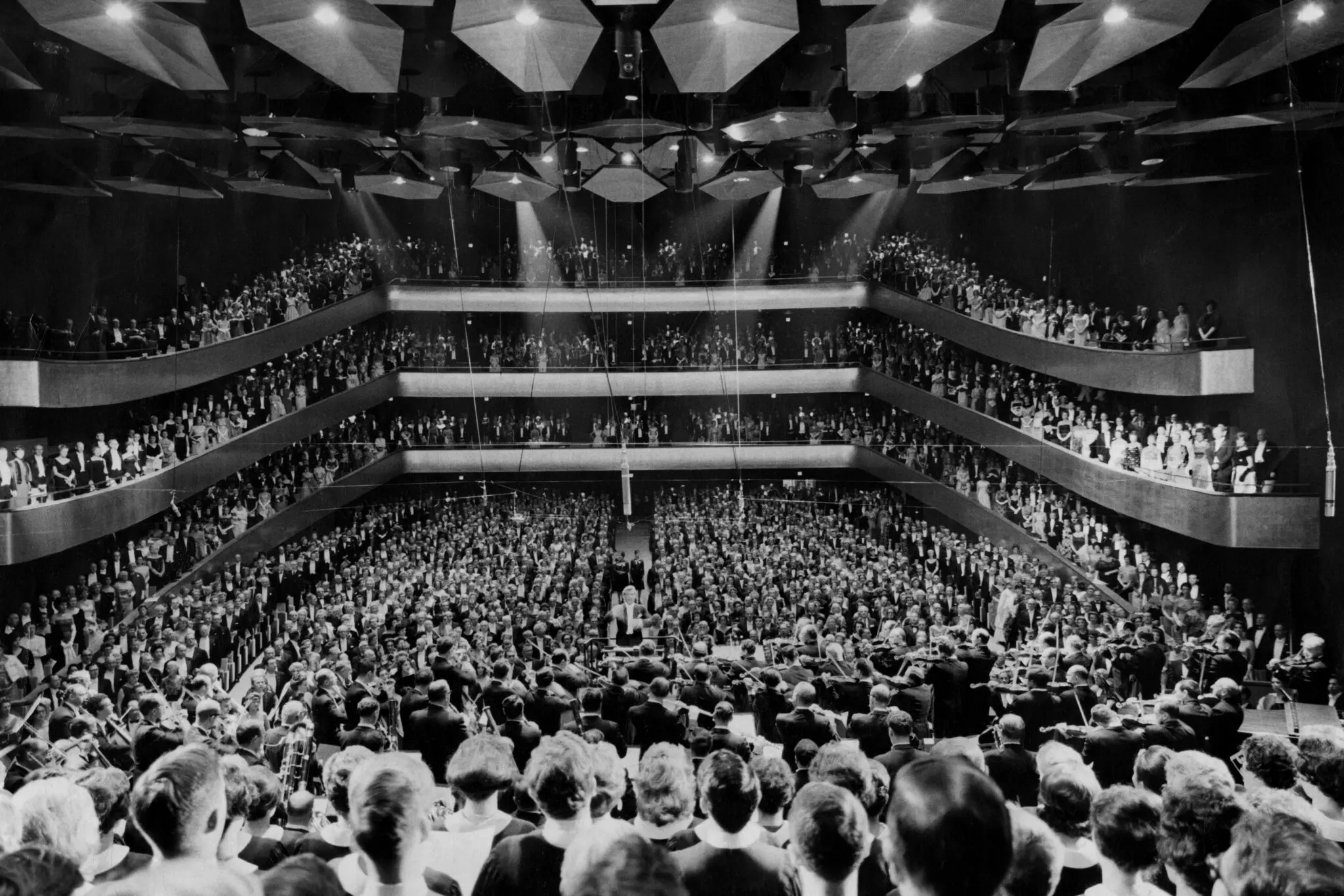

Finally, after years of missteps and and an infinite number of attempts trying to convince the Philharmonic and Lincoln Center that a change was necessary, agreement was reached to completely transform the New York City icon. The building was originally designed in 1962 by Max Abramovitz. The orchestra first moved to Philharmonic Hall, the first building to open at Lincoln Center, after spending 71 years at Carnegie Hall. Immediately though, musicians complained that they could not hear each other’s parts.

As a result, the hall was acoustically redesigned in 1976 and again in 1992. Deborah Borda, president and CEO of the New York Philharmonic said that originally (courtesy of NPR), “the hall was designed acoustically for the envelope to be for 2,200 people,” said Borda. “When the hall opened, the boards of directors of both the Philharmonic and Lincoln Center decided they wanted to have it the same size as Carnegie Hall. So, they put in 2,800 seats when it was designed for 2,200 seats.”

The New York Philharmonic’s first “open” rehearsal at the NEW David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. Musical director Jaap van Zweden conducts the orchestra on September 19, 2022.

Image courtesy of: Seattle Times, photographed by: Ronald Blum

What is now David Geffen Hall has been closed for two years; in addition, the renovation came at the enormous price tag of $550 million. Primarily in charge was the husband-and-wife team of Tod Williams and Billie Tsien (TWBTA), although many other architects, technicians, and consultants were brought on to ensure that everything went according to plan. Diamond Schmitt Architects worked hand-in-hand with TWBTA; the Canadian firm was part of the initial team and stayed on to head up revamping the main performance space which is called Wu Tsai Theater.

Aside from exceptional acoustics, a flexible concert space and public accessibility were the project’s main goals. The masterplan phase called for internal rearrangement (courtesy of Architectural Digest) “within the original building envelope: Moving the escalator and grand stairs flanking the former ticket hall back toward stage right and left exposed the original midcentury-modern columns and created an open floor plan with double the square footage on the ground level.”

Opening night at Philharmonic Hall, 1962.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Patrick A. Burns

The new concert hall was reduced in size from 2,738 to its original size of 2,200… orchestra rows were cut by ten to number 33, and two-thirds of the third tier was completely eliminated. The stage was moved forward 25 feet thanks to the fact that the concert hall has no proscenium and seven rows of wraparound seating was installed behind the performers. Finally, side tiers were curved to pay homage to the original blueprints. Seats were upholstered in a custom Jacquard by Emily Neal with Maharam.

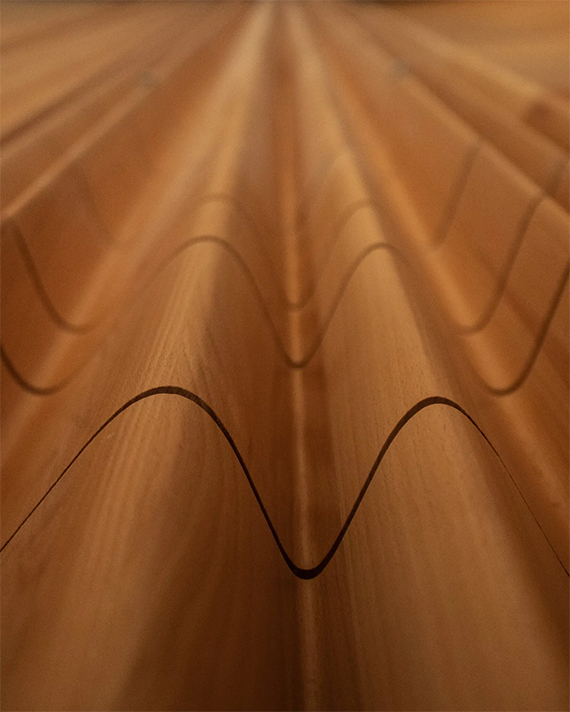

The new design gives audience members the opportunity to engage in a 360-degree experience. Working with Paul Scarbrough, principal at Akustiks, an acoustical consulting firm, “acoustics optimized undulating beech wood paneling wraps the interior; a mesh ceiling with moveable “firefly” pendants hovers above.”

The new upper level seats are now angled to face the stage… a novel idea!

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Todd Heisler

Noting that acoustics are the most important aspect to configure correctly, the architecture and design team ensured that acousticians did not play “second fiddle” to architects. In fact, Akustiks set the hall’s specifications as well as recommending the layout. The reduced seating capacity will likely improve acoustics independently, but Scarbrough did additional things such as cutting the distance from the farthest seat to the stage and allowing for “acoustic breathing room” around the musicians themselves. “Sixteen acoustic fiberglass panels hang from the ceiling to allow tuning, and a mesh ceiling is above the audience. Fabric wall banners can cover walls for amplified performances.”

It was confirmed that “The main thing that didn’t work was the ceiling over the stage being much too low, so driving too much sound energy back to the musicians too quickly, making it very hard for them to hear what was happening. The third side tier directed too much sound energy back down to the orchestra floor, where the audience would absorb it.” As such, both the walls and tiers were resurfaced with rippled beech wood paneling to cut down on the reverberation; this also replaced the 1976 renovation’s ugly beige plaster and mahogany-hued lumber.

The rippling wooden walls diffuse sound.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Todd Heisler

The new theater is more open: both literally and figuratively. Literally in that there is a lot more open space within to allow for more breathing room… in the common areas, among the audience, and for the musicians. Figuratively in that the facility plans to be more open to different types of music and entertainment. Specifically, the theater was crafted for adaptability so that it could just as easily stage a film screening as a rock concert.

Seven years ago, the entertainment mogul, David Geffen jump-started the project with a $100 million gift. The monumental gift lead to Geffen’s naming rights to the hall; but assembling the right team was vital. Deborah Borda, who ran the Philharmonic during the 1990s, returned with a goal of getting this new facility built and Katherine Farley, chair of Lincoln Center, made renovating the hall her main priority. Hiring Henry Timms as the new president and chief executive ensured that Geffen Hall would open with great leadership set on long-term stability.

Following the first rehearsal at David Geffen Hall in August, principal bassoonist since 1981 Judith LeClair said, “The first rehearsal, we were a little bit worried because it was very, very dry, but then they moved things around and it’s wonderful. You could hear what you’re doing. It’s not scary to make soft attacks anymore. It’s not a bright, brittle sound anymore. It’s just a warmer, woodier sound instead of being bright and ugly.” Music to our ears!