Architecture

The enormity of “City”

“45°, 90°, 180°,” 1972-2022.

Image courtesy of: Architectural Record, photographed by: Joe Rome (courtesy of Triple Aught Foundation)

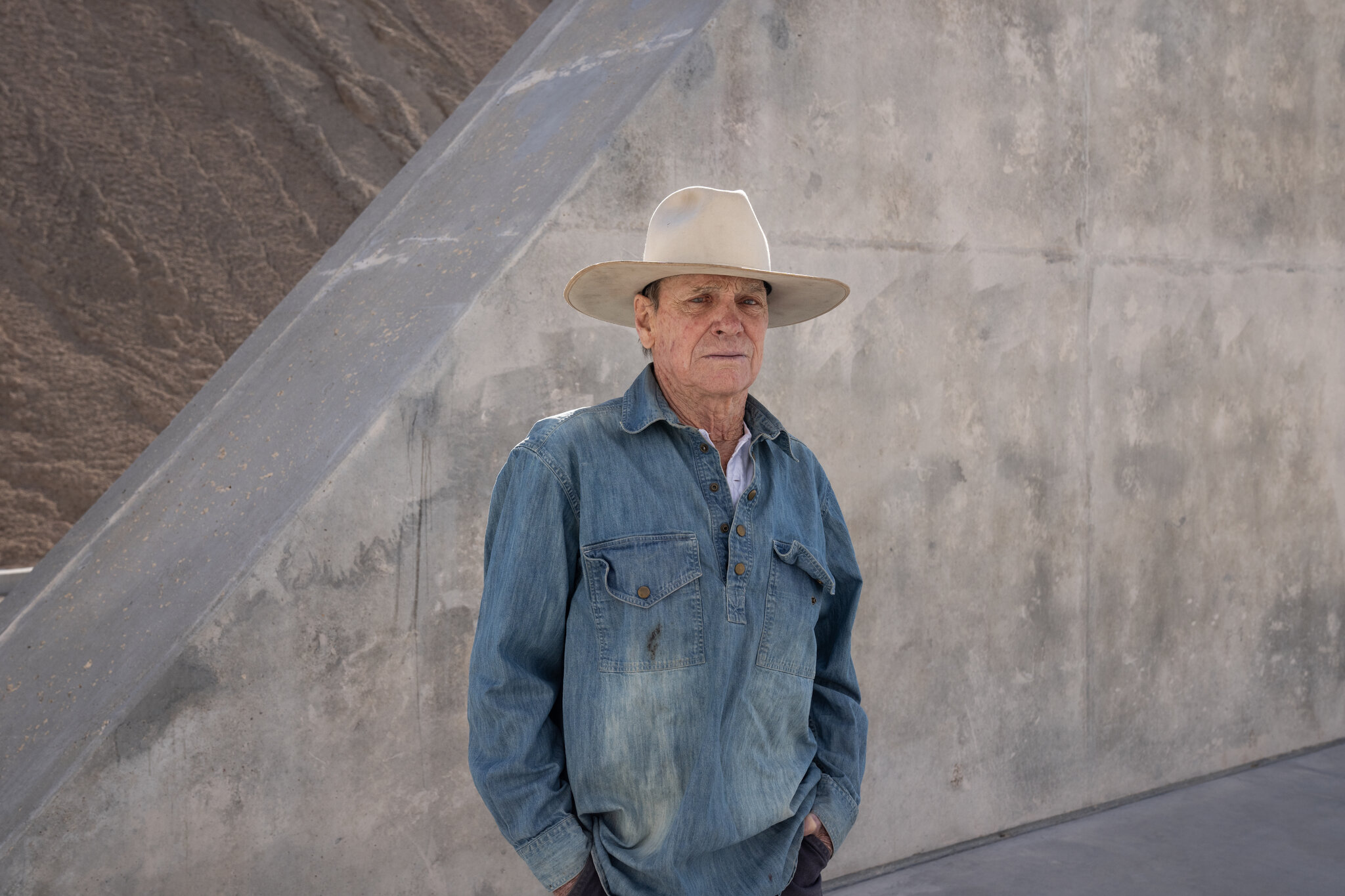

At 77 years old, Michael Heizer might finally be slowing down. The American artist just completed “City,” a $40 million landscape art mega sculpture that measures 1.5-miles-long by .5-miles-wide. “City” is in the middle of a remote stretch of the high Nevada desert where the nearest blacktop road is more than an hour away. The monumental landscape art “production” is extremely difficult to describe.

Heizer has been working on “City” for fifty years. He says that it is his (courtesy of The New York Times) “Love Letter to the Landscape. ‘This land is in my blood.'” By land, Heizer means Nevada and the Great Basin region; he is vastly different than similar artists who proclaimed themselves revolutionary and move west to make earthworks. Heizer, in fact, is the true definition of a land-art pioneer.

“Negative” statues are made by removing the earth to shape subterranean forms on the desert floor.

Image courtesy of: Dezeen, photographed by: Mary Converse

Initially, Heizer worked on “City” independently; accepting periodic commissions in order to pay for the necessary repairs of his old equipment and in order to hire helpers. Luckily in the 1980s, the director of the Dia Center for the Arts in New York, Michael Govan, a longtime admirer of Heizer, enlisted J. Patrick Lannan Jr. as a patron. A longtime philanthropist of the arts, Lannan made it possible for Heizer to hire help and buy new equipment.

Some might deduce that Heizer choose the Garden Valley because it was cheap land and plentiful in supply. However other schools of thought point out to the area’s history during the 1950s and 60s as a nuclear detonation playground from the Nevada Test Site nearby. Those who lived in the area at the time recall seeing “pink clouds and what looked like ‘snow falling in the mountains’ after a hydride test in 1962.”

Neither Heizer’s life or his art can be separated from the Nevada desert.

Image courtesy of: The New York Times, photographed by: Todd Heisler

Heizer claims that he simply wanted to honor nature with his monuments. As an abstract artist from an earlier generation of New York School artists such as Jackson Pollack, Heizer has always been curious about geometry. As such, his land-art in Nevada is specific and precise.

“City” led to the designation of Basin and Range National Monument; however, this honor created many enemies for Heizer. Nearby ranchers were furious that the government designated 704,000 acres as a national monument. Those same people were enraged that the government was telling them what they could and could not do. As a by-product, the normally solitary Heizer was told that he now has to admit visitors to his national monument.

“Complex One” is essentially an enormous mound of piled-up dirt.

Image courtesy of: Dezeen, photographed by: Mary Converse

“City’s” two big monuments are vastly different from one another. “Complex One” resembles an altar where “projecting beams align when views from a certain angle frame the complex’s facade, like one of those tricks of lenticular art.” The other, “45°, 90°, 180°,” is made up “of a concrete plaza supporting several rows of increasingly enormous triangles and rectangles. In this case, the twist is that they’re like puzzle pieces. If combined, they would form a single immense wedge.”

“City” is ongoing…

Image courtesy of: The New Yorker, photographed by: Jamie Hawkesworth

In true Heizer fashion, even though “City” is “open” to the public, it proves quite difficult to actually frequent. Only one group of six people is allowed to visit each day and reservations are spoken-for far in advance. The lucky few that score a viewing are requested to gather at Alamo, Nevada, a tiny town about 90 miles from Las Vegas. There, a staff member from the Triple Aught Foundation drives the group three hours, a third of which is on a dirt road, to Heizer’s magnum- opus.

It is impossible to understand the magnitude and enormity of “City.” That, in conjunction to the fact that it has been a work-in-progress for more than five decades and grasping the experience becomes just a little more tangible. It might take years, but seeing “City” in person appears to be well worth the wait.