Fine Art

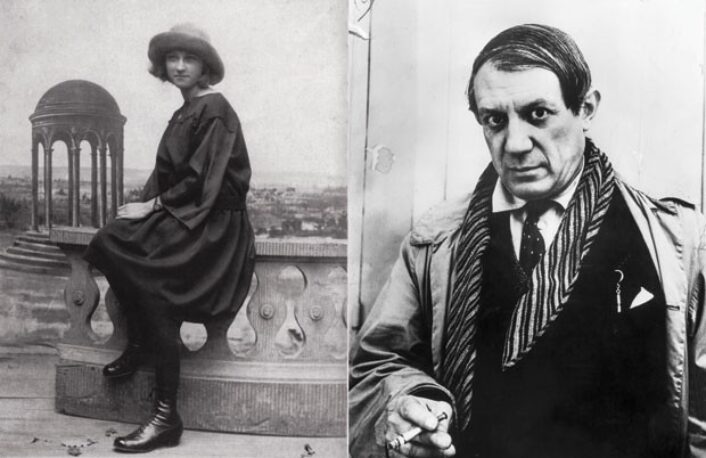

Understanding Picasso’s Blue Period

“The Old Guitarist,” 1903-04.

One of Picasso’s most famous paintings, it is displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago. It is a part of the Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection.

Image courtesy of: New City Art

One of Pablo Picasso’s most famous periods is “The Blue Period.” The work created over years 1901-1904 is extremely identifiable. Recently, the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. held a show titled, “Picasso: Painting the Blue Period.” Prior to curating this special exhibition, a lot of research was done in order to properly understand what influenced the young artist as he traveled between Barcelona and Paris.

Much of the work Picasso painted at the turn of the century was painted in shades of blue and blue-green. In addition, the subject matter was somber… inspired by his native country of Spain and the suicide of his friend, Carles Casagemas. Picasso himself says about the work he produced at the time, “I started painting in blue when I learned of Casagemas’s death.”

“The Soup,” 1903. Oil on canvas.

Image courtesy of: Smithsonian Magazine

Prior to Picasso’s Blue Period, the artist’s career looked promising; he was well known in Paris as someone with considerable talent. However as he migrated towards a subject matter that was less comfortable, a lot of the critics and public became uninterested in his work. In particular, the Spanish artist was interested in portraying society’s poor and outcast using cool blue tones to portray anguish and despair. Society was looking for upbeat, happy work and not necessarily paintings that would make them uncomfortable.

Specifically, Picasso focused on beggars, drunks, and prostitutes; society’s sick, crippled, and hungry were also commonly featured subjects. Unique during this time period is that Picasso (courtesy of Masterworks Fine Arts), “elongated his subjects’ forms, endowing them with a unique sense of haunting beauty and supernatural grace.”

“Woman Ironing,” 1901. Oil on canvas, mounted on cardboard.

Image courtesy of: Art- Picasso

The paintings from Picasso’s Blue Period offer insight as to how distressed he was with inequality between different classes. It is clear that Picasso was deeply distraught by the poor treatment of the working class during the Industrial Revolution. The destitute figures Picasso portrays commonly perform everyday, mundane tasks; this points towards lives that are ” less than ideal.”

His internal conflict, in addition to the grief Picasso felt because of many personal losses he had already experienced in his young life, left the artist troubled. By 1901, he hadn’t yet found his “own voice”… either artistically or personally. As the curator William H. Robinson explained to Artsy, Picasso “formed a pattern of events suggesting that artists—at least those who live in opposition to mainstream society—are fated to suffering and tragedy.”

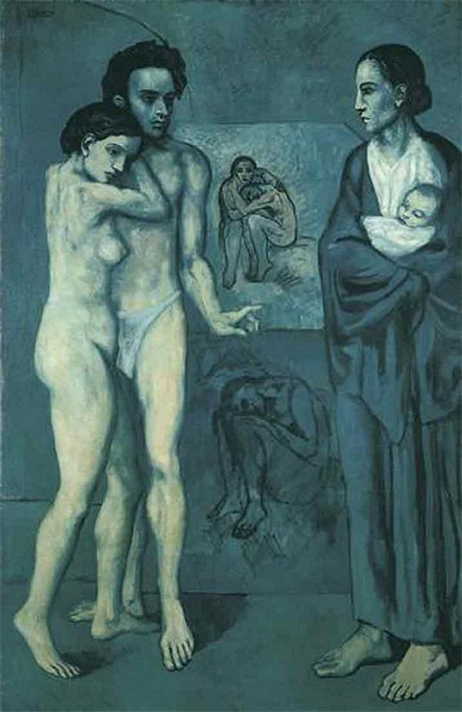

“La Vie,” 1903.

As a part of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s permanent collection, “La Vie” was painted in Barcelona, during a time when Picasso was not seeing any financial success.

Image courtesy of: Masterworks Fine Art

The pieces painted during this turbulent time in Picasso’s life addressed many philosophical, symbolic, and humanitarian themes. Perhaps one of the artist’s most familiar and conflicting works is “La Vie.” This painting, painted in 1903, is often considered to be the pinnacle of The Blue Period. Historians have alleged that “La Vie” encompasses references to birth, death, and redemption… all hidden in plain sight. The predominately blue-toned painting presents a nude couple and a robed woman cradling a baby. The figures stand in front of two paintings that feature despaired subjects.

Interestingly, this painting began as a self-portrait; however unconsciously, Picasso found the figures transformed to that of his late friend, Casagemas. The National Gallery of Art suggested (courtesy of Masterworks FineArts), “Picasso metaphorically allows his subjects to escape their fate and occupy a utopian state of grace. Some are afflicted with blindness, a physical condition that symbolically suggests the presence of spiritual inner vision.”

Inspecting “La Misereuse Accroupie,” 1902. Crouching woman is a perfect example of some of the canvas complexities that have been recently revealed through scientific studies.

Image courtesy of: The Guardian

Over the past twenty years, researchers have uncovered hidden “underpaintings” in a number of Picasso’s Blue Period works. There are two possible reasons for the “underpaintings”: was this a financial decision or did Picasso feel as thought he could “do better?” Without financial stability, it might be that the young artist could not afford new canvases. Or, as a young artist and a quick learner, it might be that Picasso realized that he could far surpass his original works.

Evidence points to stray brushstrokes in the opposite direction of the final composition. Technological improvements and studies include the use of x-radiograms and x-ray fluorescence to analyze those hidden secrets. Tiny fragments were removed from the painting and analyzed to reveal more secrets underneath. Marc Walton of Northwestern University explained the new surprises to The Guardian, “This gives us a little bit better sensibility about how this layered structure has developed, because some pigments are only in one layer and not another.”