Studio Collective at Virginia Tech July 2016

SUZANNE LOVELL INC.

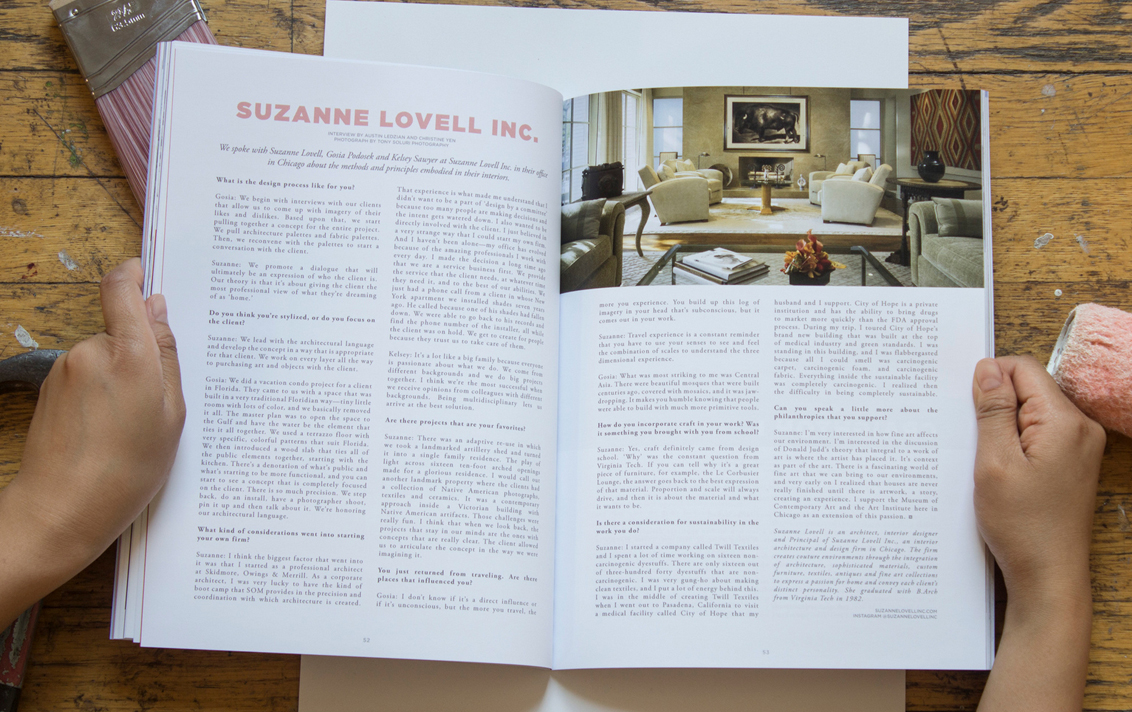

We spoke with Suzanne Lovell, Gosia Podosek and Kelsey Sawyer at their office in Chicago about the methods and principles

embodied in their interiors.

What is the design process like for you?

Gosia: We begin with interviews with our clients that allow us to come up with imagery of their likes and dislikes. Based upon that, we start pulling together a concept for the entire project. We pull architecture palettes and fabric palettes. Then, we reconvene with the palettes to start a conversation with the client.

Suzanne: We promote a dialogue that will ultimately be an expression of who the client is. Our theory is that it’s about giving the client the most professional view of what they’re dreaming of as ‘home.’

Do you think you’re stylized, or do you focus on the client?

Suzanne: We lead with the architectural language and develop the concept in a way that is appropriate for that client. We work on every layer all the way to purchasing art and objects with the client.

Gosia: We did a vacation condo project for a client in Florida. They came to us with a space that was built in a very traditional Floridian way – tiny little rooms with lots of color, and we basically removed it all. The master plan was to open the space to the Gulf and have the water be the element that ties it all together. We used a terrazzo floor with very specific, colorful patterns that suit Florida. We then introduced a wood slab that ties all of the public elements together, starting with the kitchen. There’s a denotation of what’s public and what’s starting to be more functional, and you can start to see a concept that is completely focused on the client. There is so much precision. We step back, do an install, have a photographer shoot, pin it up and then talk about it. We’re honoring our architectural language.

What kind of considerations went into starting your own firm?

Suzanne: I think the biggest factor that went into it was that I started as a professional architect at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. As a corporate architect, I was very lucky to have the kind of boot camp that SOM provides in the precision and coordination with which architecture is created. That experience is what made me understand that I didn’t want to be a part of ‘design by committee’ because too many people are making decisions and the intent gets watered down. I also wanted to be directly involved with the client. I just believed in a very strange way that I could start my own firm. And I haven’t been alone – my office has evolved because of the amazing professionals I work with every day. I made the decision a long time ago that we are a service business first. We provide the service that the client needs, at whatever time they need it, and to the best of our abilities. We just had a phone call from a client in whose New York apartment we installed shades seven years ago. He called because one of his shades had fallen down. We were able to go back to his records and find the phone number of the installer, all while the client was on hold. We get to create for people because they trust us to take care of them.

Kelsey: It’s a lot like a big family because everyone is passionate about what we do. We come from different backgrounds and we do big projects together. I think we’re the most successful when we receive opinions from colleagues with different backgrounds. Being multidisciplinary lets us arrive at the best solution.

Are there projects that are your favorites?

Suzanne: There was an adaptive re-use in which we took a landmarked artillery shed and turned it into a single family residence. The play of light across sixteen ten-foot arched openings made for a glorious residence. I would call out another landmark property where the clients had a collection of Native American photographs, textiles and ceramics. It was a contemporary approach inside a Victorian building with Native American artifacts. Those challenges were really fun. I think that when we look back, the projects that stay in our minds are the ones with concepts that are really clear. The client allowed us to articulate the concept in the way we were imagining it.

You just returned from traveling. Are there places that influenced you?

Gosia: I don’t know if it’s a direct influence or if it’s unconscious, but the more you travel, the more you experience. You build up this log of imagery in your head that’s subconscious, but it comes out in your work.

Suzanne: Travel experience is a constant reminder that you have to use your senses to see and feel the combination of scales to understand the three dimensional experience.

Gosia: What was most striking to me was Central Asia. There were beautiful mosques that were built centuries ago, covered with mosaics, and it was jaw-dropping. It makes you humble knowing that people were able to build with much more primitive tools.

How do you incorporate craft in your work? Was it something you brought with you from school?

Suzanne: Yes, craft definitely came from design school. ‘Why’ was the constant question from Virginia Tech. If you can tell why it’s a great piece of furniture, for example, the Le Corbusier Lounge, the answer goes back to the best expression of that material. Proportion and scale will always drive, and then it is about the material and what it wants to be.

Is there a consideration for sustainability in the work you do?

Suzanne: I started a company called Twill Textiles and I spent a lot of time working on sixteen non-carcinogenic dyestuffs. There are only sixteen out of three-hundred forty dyestuffs that are non-carcinogenic. I was very gung-ho about making clean textiles, and I put a lot of energy behind this. I was in the middle of creating Twill Textiles when I went out to Pasadena, California to visit a medical facility called City of Hope that my husband and I support. City of Hope is a private institution and has the ability to bring drugs to market more quickly than the FDA approval process. During my trip, I toured City of Hope’s brand new building that was built at the top of medical industry and green standards. I was standing in this building, and I was flabbergasted because all I could smell was carcinogenic carpet, carcinogenic foam, and carcinogenic fabric. Everything inside the sustainable facility was completely carcinogenic. I realized the difficulty in being completely sustainable.

Can you speak a little more about the philanthropies that you support?

Suzanne: I’m very interested in how fine art affects our environment. I’m interested in the discussion of Donald Judd’s theory that integral to a work of art is where the artist has placed it. It’s context as part of the art. There is a fascinating world of fine art that we can bring to our environments, and very early on I realized that houses are never really finished until there is artwork, a story, creating an experience. I support the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Art Institute here in Chicago as an expansion of this passion.

Suzanne Lovell is an architect, interior designer and Principal of Suzanne Lovell Inc., an interior architecture and design firm in Chicago. The firm creates couture environments through the integration of architecture, sophisticated materials, custom furniture, textiles, antiques and fine art collections to express a passion for home and convey each client’s distinct personality. She graduated with B.Arch from Virginia Tech in 1982.

Interview by Austin Ledzian and Christine Yen, Photograph by Tony Soluri Photography